HETL Note: We are pleased to present “The Development of ICT Competence within Bologna-Adapted Language Degrees” – an academic article by Dr. María Luisa Pérez Cañado. The article discusses how digital competencies can be incorporated in language university degrees following the implementation of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) competencies framework. The author provides research-based evidence and describes five pedagogical innovation projects carried out at the University of Jaén which illustrate how explicit development of multiple literacies can be successfully achieved. The article shows how the development of ICT competence has improved the learning process by increasing student satisfaction and supporting innovative teaching styles. You may submit your own article on the topic or you may submit a “letter to the editor” of less than 500 words (see the Submissions page on this portal for submission requirements).

Author Bio: Dr. María Luisa Pérez Cañado is Associate Professor at the Department of English Philology of the University of Jáen, Spain, where she is also Vice Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Education. Her research interests are in applied linguistics, English for specific purposes, and the intercultural component in language teaching with numerous publications in scholarly journals and edited volumes. Maria Luisa is also the author of four books on the interface of second language acquisition and second language teaching, the editor of several books, and journal guest editor and reviewer. She has taught in Belgium, Poland, Germany, Portugal, Ireland, England, Mexico and the United States, as well as and at several Spanish universities. Currently, Maria Luisa is in charge of the implementation of the European Credit System in English philology at the University of Jaén and has recently been granted the Ben Massey award in recognition of the quality of her scholarly contribution and the difference it has made to higher education. Dr. Cañado can be reached at [email protected]

Author Bio: Dr. María Luisa Pérez Cañado is Associate Professor at the Department of English Philology of the University of Jáen, Spain, where she is also Vice Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Education. Her research interests are in applied linguistics, English for specific purposes, and the intercultural component in language teaching with numerous publications in scholarly journals and edited volumes. Maria Luisa is also the author of four books on the interface of second language acquisition and second language teaching, the editor of several books, and journal guest editor and reviewer. She has taught in Belgium, Poland, Germany, Portugal, Ireland, England, Mexico and the United States, as well as and at several Spanish universities. Currently, Maria Luisa is in charge of the implementation of the European Credit System in English philology at the University of Jaén and has recently been granted the Ben Massey award in recognition of the quality of her scholarly contribution and the difference it has made to higher education. Dr. Cañado can be reached at [email protected]

Krassie Petrova and Patrick Blessinger

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Development of ICT Competence within Bologna-Adapted Language Degrees

María Luisa Pérez Cañado

University of Jaén, Spain

Abstract

This article focuses on two pivotal concepts within the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) framework: competencies and information and communication technologies (ICT). It provides research-based evidence from two quantitative and qualitative studies on the current status regarding the incorporation of competencies and ICT in Bologna-adapted language degrees, concluding that much is still needed in order to conform to EHEA standards. It also addresses whether and why these cornerstones in European convergence should be incorporated into such degrees, making a compelling case in favour of doing so. On the basis of the findings, practical recommendations about implementing ECTS (European Credit Transfer System) are provided. The specific recommendations stem from five pedagogical innovation projects carried out at the University of Jaén that are used to illustrate how multiple literacies are being developed in each context. The article concludes that the development of ICT competencies has improved the learning process, increased the satisfaction and motivation of participating cohorts, helped lecturers involved develop new teaching styles, and helped achieved the objectives underlying EHEA, particularly in terms of ICT competence development.

Keywords: EHEA, competencies, ICT, language degrees, pedagogical innovation

INTRODUCTION

It is an increasingly acknowledged fact that we are currently living a time of immense upheaval in higher education (HE). A series of forces –among them, globalization, technology, and competition (Green, Eckel, & Barblan, 2002) – are reconfiguring HE across continents and calling for an immediate response. In Ma’s (2008, p. 65) words, “Higher education in the world has experienced a drastic change in the last few decades”. When applied to the language teaching arena, this transformation acquires an even sharper relief. As Brantmeier (2008, pp. 308) has pointed out, “Issues of language use, learning, and teaching across national and international boundaries are increasingly situated at the forefront in today’s world”. Indeed, we are confronted with a language challenge in HE (Tudor, 2008) which affects not only Europe, but also Canada and the U.S. (Pérez Cañado, 2010a).

In Europe, the specific policy framework which has been established to guide action in this arena is the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). The creation of EHEA through what has come to be known as the Bologna Process is serving as a powerful lever for change in language teaching at HE and has been pushed forward via a set of conventions, declarations, and communiqués. From the initial Sorbonne (1998) and Bologna Declarations (1999) to the more recent Budapest-Vienna Declaration (2010) and Leuven Communiqué (2009), significant steps have been taken to bolster the European convergence process.

A number of important objectives have been set forth over the course of the past decade to consolidate the EHEA. These involve the establishment of comprehensible and comparable degree systems based on three cycles –undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral, the adoption of a European Credit Transfer System (ECTS), the encouragement of international mobility, the improvement of European cooperation and quality assurance, the enhancement of the competitiveness and attractiveness of HE in Europe, and the stimulation of the European dimension of HE. The shift to the practical application of these goals is particularly conspicuous in the Graz Declaration (2003) and the Berlin Communiqué (2003), and acquires greater relevance in the Glasgow Declaration (2005) and Bergen Communiqué (2005). More specifically the methodological adjustment involved in implementing ECTS that involves competence development, innovative teaching approaches, student-centeredness, and lifelong learning has becoming pivotal in the application of EHEA and achieving its objectives.

For many (e.g., Benito & Cruz, 2007; Blanco, 2009; Poblete Ruiz, 2006), the cornerstone of the transformation being caused by EHEA is to be found in the application of competence-based teaching. The notion of competence involves not only knowledge, but also skills, attitudes, and values, and entails the capacity to perform successfully in an academic, professional, or social environment (OECD, 2005, p. 2). On both sides of the Atlantic, the onus is now on developing a set of competencies that will prepare graduates to become successful professionals who can meet societal needs (Pratt et al., 2008). The ultimate aim of the competence-based model is to form flexible and adaptable professionals who can apply competencies to the varied, unforeseeable, and complex situations they will encounter throughout their personal, social, and professional lives (Cano García, 2008; Pérez Gómez, Soto Gómez Sola Fernández, & Serván Núñez, 2009b), and who can thus become active and useful citizens in our democratic society.

In order to attain such professional success, it is widely consensual that information and communication technologies (ICT) are paramount: “ … while we can’t imagine, much less guarantee, what the jobs of the future will be, we can be fairly sure that they will occur in post-industrial contexts, will involve digital technologies, and will require multiple literacies” (Pegrum, 2009, p. 54). Indeed, ICT are at present inextricably linked to competence development. In addition to being one the core generic competencies which most European universities have worked into their Bologna-adapted degrees, the potential of technological or digital competence for enhancing the student-centered learning process has been underscored in the official EHEA literature. According to Benito and Cruz (2007, p. 104), ICT are not a new fad, but a crucial tool which, in combination with the EHEA, will foster pedagogical innovation and allow the agents involved in the teaching-learning process to expedite knowledge-building and competence development.

Given the heightened importance of competencies and ICT within the EHEA, this article seeks to address three key questions regarding where we currently stand. It will begin by providing research-based evidence on whether we are incorporating both these concepts into Bologna-adapted language degrees and if it makes sense to do so. It will then offer practical specifications on how to develop them by expounding on five pedagogical innovation projects carried out at the University of Jaén and reporting on their outcomes in order to determine how these initiatives have worked. The most important conclusions which our studies and projects have enabled us to arrive at will be outlined in the final section.

QUESTION 1: ARE COMPETENCIES AND ICT BEING INCORPORATED INTO BOLOGNA-ADAPTED LANGUAGE DEGREES?

With respect to the first question and in order to determine where language degrees stand in the process of EHEA compliance across Europe, the ESECS (English studies in the European credit system – www.esecs.eu) research group has recently conducted two complementary large-scale and outcome-oriented studies The first of them, ADELEEES (Adaptación de la Enseñanza de Lenguas al EEES: Análisis del estado actual, establecimiento de redes europeas y aplicación a los nuevos títulos de grado, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Programa Estudios y Análisis, Ref. EA2008-0173, 2008-2009) was an essentially qualitative endeavor, aimed at designing, validating, and applying four sets of questionnaires to measure the degree of satisfaction of professors and students, to determine the main methodological aspects involved in the teaching-learning process, to estimate the real workload of both stakeholders, and to analyze the competencies which are actually developed and evaluated in language degrees. Its ultimate aim was to carry out an in-depth analysis of the current application of ECTS to language teaching in Europe in order to facilitate the readjustment needed prior to designing the new degree structures.

In turn, FINEEES (La Filología Inglesa en el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior, evaluated by the ANEP, 2008-1010, Universidad de Jaén, Plan de Apoyo a la Investigación, Acción 16, Ref. UJA_08_16_35) complemented the first study from a predominantly quantitative data analysis viewpoint. It took advantage of the unique opportunity offered by the University of Jaén where the same subjects are taught often by the same teachers employing two different methodologies: an English philology ECTS stream, and traditional methodology class in English philology + Tourism; this allowed to conduct a quasi-experimental study into the effects of both methodologies, factoring in a series of co-variants such as gender, motivation, and performance in the Selectividad exam (at the time of the writing these results were still being analyzed). In addition qualitative data were gathered form focus group interviews in order to employ methodological and investigator triangulation. The objective of the interviews was to identify the main strengths and weaknesses of the implementation of ECTS in English philology at the University of Jaén and to compare the new credit system (in English philology) to the traditional one (in English Philology + Tourism). It was envisaged that the outcomes would inform the design of the new degree structures at the University.

Taken jointly, the outcomes of both studies allowed a detailed portrayal of where the University stands in conforming to the Bologna standards in the English language degrees. To begin with, vis-à-vis competencies, it transpired that while the ECTS stream was aware of their existence, development, and evaluation, the traditional methodology stream was completely unfamiliar with the concept. However, with respect to the new credit system, both teachers and students acknowledge that it was almost left unused and competencies were seldom evaluated , with learners even questioning whether their professors were prepared to do so. This finding is consistent with the results reported by other authors (Madrid & Hughes, 2009; Nieto García, 2007; Ron Vaz, Fernández Sánchez, & Nieto García, 2006), who stress that greater awareness-raising of competencies is required.

The outcomes obtained for materials and resources were equally disheartening. More similarities rather than differences between teacher and student perceptions were . Advanced ICT resources such as Second Life, videogames, digital storytelling, wikis, blogs, webquests, and teaching software were very sparsely used. These findings are surprising, particularly considering the extremely beneficial effects which ICT is exerting on language learning and competence development: a significant number of recent studies advocate the incorporation of these resources into the language classroom, as discussed in the next section.. Textbooks, educational web portals, realia, audio and video material, and online and print dictionaries were not very frequently employed either, albeit more assiduously than those materials related to new technologies. On the opposite side of the spectrum were materials compiled or created by the teacher, PowerPoint presentations, and Internet downloads, which came across as the most frequently employed resources by teachers (see Pérez Cañado, 2011a for a detailed rendering of these outcomes).

Thus, we can state in no uncertain terms that the answer to our first question is in the negative: competencies and ICT are not as yet being adequately incorporated into Bologna-adapted language degrees. Considerable strides still need to be taken in this area in order to conform to EHEA standards. This takes us to our second question: is it worth our while? Should we be incorporating digital competence into our graduate and undergraduate studies?

QUESTION 2: SHOULD DIGITRAL OR TECHNOLOGICAL COMPETENCE BE INCORPORATED INTO BOLOGNA-ADAPTED LANGUAGE DEGREES?

The empirical evidence available in the field provides an unequivocal answer to the question above: ICT are pivotal in bringing about a reconfiguration of teacher and student roles and in operating the shift to a learner-centered pedagogy of autonomy (Pérez Gómez et al., 2009e). The CIDUA Report (2005) already foregrounds the effectiveness of new technologies and virtual learning environments in boosting student motivation, in fostering their active involvement in the learning process, and in being more germane to their needs, interests, and expectations. This is also underscored in the report by the Red Interuniversitaria de Innovación Docente de las Universidades Andaluzas (2008: 15-16), which views ICT as a fruitful means to foster cooperative learning, stimulatestudent problem-solving capacity, promote interaction between both agents in the teaching-learning process, accentuate the link to real-world situations, and cater for diverse learning styles. According to Pennock-Speck (2009), ICT support learner autonomy and interaction, expedite the move away from ex-cathedra lecturing, and help teachers step down from being the center of the learning process to take on a more peripheral role. ICT are also a powerful means to wedge in innovation in HE, with which it is seen as almost synonymous (Pennock-Speck, in press for 2012). All in all ICT can enhance teaching and help improve the learning of discipline-specific content; the technology favors the acquisition of competencies and promotes English language development – a particularly significant remit in our context, as Pennock-Speck (in press for 2012) aptly notes. With respect to a degree in English in a non-English-speaking country like Spain, alongside providing opportunities for students to acquire content and competencies, we must make sure that they also acquire the most important of the specific competences, that is, the ability to communicate in English.

It is thus not surprising that the use of ICT in ECTS pilot programs (in Spanish universities) has been found to heighten students’ motivation (Pennock-Speck, 2009) and to generate positive attitudes towards the learning process (Gregori-Signes & Pennock-Speck, 2007). The official EHEA documents therefore propound promoting ICT in all of their manifestations and possibilities (Pérez Gómez et al., 2009a, 2009d).

Manifold quantitative and qualitative investigations into the use of new technologies have confirmed their many merits. Positive effects of diverse ICT options on language learning within ECTS contexts have been documented in the recent specialized literature. The use of computer assisted language learning (CALL) understood in the inclusive sense (Levy & Hubbard, 2005: 148) and data-driven learning (DDL) were found to significantly impact English philology freshmen’s writing skills in five aspects previously diagnosed as problematic at Spanish university level: spelling, articles, verbal complementation, prepositions, and vocabulary. At the same time these approaches were found to promote discovery-learning, boost motivation, and enhance learner autonomy (Pérez Cañado & Díez Bedmar, 2006).

Virtual learning environments have equally proved beneficial in the EHEA context. Brígido Corachán (2008) found that the use of threaded forums for collaborative e-learning within literature subjects dramatically changed the teacher-student learning dynamics, enhanced the creative processes of knowledge construction, strengthened interactive and problem-solving skills, and helped build a classroom climate governed by trust and confidence. Similarly Ceballos Muñoz (2010) employed a virtual course management system to set up cross-curricular electronic tutorials which had positive repercussions for students’ written and oral comprehension and production skills in English, while simultaneously favoring the acquisition of contents and creating new student and teacher roles more germane to the agenda underlying EHEA. Finally, Pérez Cañado (2010b) documented the significant lexical improvement of English philology freshmen through the use of the ILIAS virtual learning environment, along with an increase in motivation, autonomy, and lifelong learning strategies of the participating student body.

A similar amelioration in lexical competence transpired from Torralbo Jover’s (2008) study, which involved the use of podcasts to enhance the vocabulary acquisition of English philology undergraduates within an ECTS scheme. The offer was embraced with enthusiasm and positive attitude.. In a similar context, both Gregori-Signes (2008) and Alcantud Díaz (2010) found that digital storytelling fostered innovation and methodological plurality (e.g., via project work and collaborative learning). It introduced creativity, independence, and personalization in the learning process, thereby subverting traditional teacher and learner roles. Skill development, oral and written comprehension, and the acquisition of ICT and intercultural competencies were promoted and motivation was enhanced.

The outcomes related to blended learning obtained by Zaragoza Ninet and Clavel Arroitia (2008; 2010) are no less auspicious. They ascertained that the ICT option fostered the acquisition of generic, competence-specific, linguistic, and technological competencies. It also favored the introduction of varied learning modalities and groupings, and helped the learner become more active, participative, and committed. It re-engineered teacher and student roles, creating a new type of classroom dynamics, one with strengthened teacher-student contact and rapport. Lifelong learning beyond in-site tuition was equally promoted, leading to increased academic success.

Finally, computer-mediated communication and telecollaboration have also been revealed as powerful tools to accommodate the underpinnings of the EHEA. Jordano de la Torre (2008) used, with great success, instant messaging and webinars to develop the oral competence of her students, make the link to the professional sphere, and increase intercultural awareness. In turn, Pérez Cañado and Ware (2009) and Kessler and Ware (in press for 2012) have illustrated how telecollaboration can make a unique contribution to the development of professional, disciplinary, and academic subject-specific competences along with generic cross-curricular competences (e.g., interpersonal, systemic, instrumental). The authors also evinced how the main principles of telecollaboration satisfy the underlying philosophy of the EHEA and how the methodological plurality inherent in the ECTS system (including the gamut of learning modalities and significantly diversified evaluation system) can be accommodated from a more practical perspective. They also observed that the use of telecollaboration impinged on the participating students’ attitudes towards language learning and improved their English language skills (especially grammar and vocabulary) by giving them an insight into the American culture, and increasing their confidence, motivation, learner autonomy, and cooperation. Overall, it paved the way towards a new teaching style on the part of the lecturers involved, one where ICT are incorporated in language teaching, and coordination and cooperation among the teaching staff are increasingly present.

Thus, the findings in the literature seem to make a compelling case for the incorporation of ICT into the new language learning scenario provided by the implementation of the ECTS. If the extant research has shown that digital competence should be developed, but that this is scarcely being done, how exactly can we go about explicitly integrating it into Bologna-adapted language degrees? The next section attempts to answer this third query by signposting relevant practice stemming from five pedagogical innovation projects carried out at the University of Jaén.

QUESTION 3: HOW CAN ICT COMPETENCE BE DEVELOPED?

In order to take ICT competence to the grassroots level in language degrees, three principles are being followed at the University of Jaén: meeting the key conditions for effective use of ICT, incorporating ICT explicitly, and developing multiple literacies.

Key Conditions for Effective Use of ICT

We fully concur with Pegrum’s (2009, p. 49) view that “… digital literacies … are essential to the personal, social and professional futures of today’s students, as well as to the political and economic futures of their societies”. However, the incorporation of ICT competence into ECTS classrooms should be done carefully and be viewed as a complement to in-class tuition – not as a replacement of traditional teaching (Pennock-Speck, in press for 2012). As this same author puts it (Pennock-Speck, 2009: 173-174), “The possible benefits of ICT are obvious, but at the same time, new technologies are not by themselves a cure-all”. This is why he finds it necessary to set forth three conditions for their use (Pennock-Speck, in press for 2012), which we fully subscribe.

The first of them (Ceffort) is that it should not be too time-consuming for teachers to design and put into practice activities and methodologies dependent on new technologies, nor should they involve an inordinate workload for the students. Either of these outcomes would inevitably lead to frustration and the rejection of ICT. Secondly, it should not be too expensive (CEcon), as this would mean resilience on the part of universities to subsidize its use. In this sense, it is important to invest not only in hardware and software, but especially in what Pegrum (2009: 53) terms “wetware”; that is, the human competence essential to make the most of technology. Thirdly, and perhaps the most important condition, is that ICT should be used only if it brings something new or innovative to teaching practice or gives the students more opportunities to acquire the knowledge and competencies they need (CInnov). Contravening any of these conditions, the author claims, will mean the ICT activity will either be superfluous, redundant, or counterproductive –or all of the above.

Incorporating Digital Competence Explicitly

Secondly, we are of the camp that digital competence should be explicitly incorporated into official course catalogues and not be left to be implicitly picked up through content teaching. In this sense, we have followed the three ways of incorporating this competence into the HE curriculum propounded by Poblete Ruiz (2008):

- We have incorporated it in seminars or workshops which are geared at developing this competence, among others (e.g., the ECTS seminar system in English Philology at the University of Jaén –cf. Pérez Cañado, 2011b).

- We have organized beginners courses which focus on the contents of the targeted competencies (e.g. a pre-freshman year course on pivotal generic competencies).

- We have integrated it in our modules or subjects, establishing different levels of mastery so that each subject can work on it at a certain levels, with a progression through the different grades.

This has been done both at graduate and undergraduate levels, by tearing apart the different curricular components of technological competence and breaking it down in terms of contents, methodology (activities which develop it), other related competencies, indicators of achievement and levels of mastery, evaluation procedures and instruments, and notional learning time (i.e. the estimated number of hours for their acquisition in our specific subject). Detailed templates based on Terrón López and García García’s (in press for 2012) innovative proposal have been drawn up for digital competence, such as the one provided below for the new undergraduate degree in English Studies (cf. Table 1). Through this detailed planning of all the elements which factor into competence achievement, we hope to supersede mere content instruction and to ensure careful thought is put into the time and effort required for adequate competence mastery.

| COMPETENCE DENOMINATION | |

| Denomination | Use of ICT tools, programs, and applications |

| Code | G10 |

| DEFINITION OF THE COMPETENCE | |

| Definition | Use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) as tools for expression and communication, to access sources of information, as a means to save data and documents, for presentations tasks, for learning and research purposes, and for cooperative learning. |

| Description in terms of learning outcomes |

|

| Required competencies | Basic user level of Microsoft Office programs and the Internet |

| Related competencies | E17, G11, E1, E16 |

| COMPETENCE DEVELOPMENT | |

| Learning activities to develop the competence |

|

| ASSESSMENT | |

| Competence level indicators (following Villa Arias & Poblete Ruiz 20082) |

|

| Assessment procedures |

– Oral presentation through a peer tutoring project – Telecollaboration project – VLE project |

| Assessment instruments |

|

| NOTIONAL LEARNING TIME | |

| 5 hours of in-class tuition (seminars) and 15 hours of independent study (preparation of PowerPoint presentation, online activities in the VLE project, weekly communication with telecollaboration partners through Blackboard, podcast listenings) => 20 hours | |

Table 1. Template for generic competence G10

The explicit incorporation of digital competence into specific subjects has also been achieved via five pedagogical innovation projects developed at our University uninterruptedly from 2004-2005 until present.

The first of them (2004-2005) used computer-assisted language learning (CALL), understood in the inclusive sense (Levy & Hubbard, 2001: 148), and data-driven learning (DDL) to raise awareness of the main writing weaknesses of English Philology freshman at the University of Jaén. The students were familiarized with tools in Word, search engines such as Google (for the consciousness-raising of spelling), dictionaries on-line (for colligations), and the BNC online service (for spelling and lexical collocations and colligations) to help them improve their performance on seven aspects previously identified as problematic for writing at Spanish University level: punctuation, spelling, articles, verb tenses, verbal complementation, prepositions, and vocabulary (cf. Pérez Cañado & Díez Bedmar, 2006).

For two consecutive academic years (2006-2008), a telecollaboration project was set up with Southern Methodist University at Dallas. It was a language-based, feedback-focused, e-tutoring experience for pedagogical purposes, whereby each Jaén freshman was assigned a Dallas tutor with whom (s)he had to communicate on a weekly basis to complete a series of clear-cut tasks via the Blackboard platform. These activities focused on all four skills, albeit with a special emphasis on writing. The Dallas tutor, a pre-service teacher specializing in ELT methodology, then provided form-focused feedback on the outcomes of each task, which the Spanish freshman took into account in honing the final product (cf. Pérez Cañado & Ware, 2009; Ware & Pérez Cañado, 2007).

The subsequent two projects – Developing Lexical Competence via VLE (2006-2007) and INNOFIL: La Innovación Docente en Filología Inglesa en el Marco del EEES (2007-2009) – centered on vocabulary development, in response to the worrying decline in lexical performance of freshmen in our degree from the February to the June exams. Virtual learning environments (the ILIAS platform at our University, a course management system similar to Moodle), sitcoms and TV series, podcasts and vodcasts, Internet texts, and blogs and wikis were all employed to counter the significant worsening ascertained in lexical performance (cf. Pérez Cañado, 2010b; Torralbo Jover, 2008).

Finally, over the course of these past two academic years (2009-2011), the DEVALCO Project (Desarrollo y Evaluación de Competencias en Estudios Ingleses) has allowed us to carry out the curricular development of 12 core generic and specific competencies in our new Bologna-adapted degrees, to design original materials in order to develop them, and to validate evaluation rubrics to assess them (cf. Pérez Cañado, 2011b).

These projects have been accompanied by quantitative studies with a pre-test/post-test control group design, complemented with qualitative questionnaires to gauge the attitudes generated in the participating student body (cf. Conclusion for some of the results).

Developing Multiple Literacies

Via these projects, the multiple components of digital literacy have been unpacked and worked on. Following primarily Shetzer and Warschauer (2000) and Pegrum (2009), five main types of literacies have been incorporated into our teaching: computer or technological literacy; information, search, filtering, or critical literacy; multimedia or multimodal literacy; CMC and multicultural literacy; and personal, participatory, and network literacy. We now canvass each one, exemplifying how it has been explicitly covered through our projects.

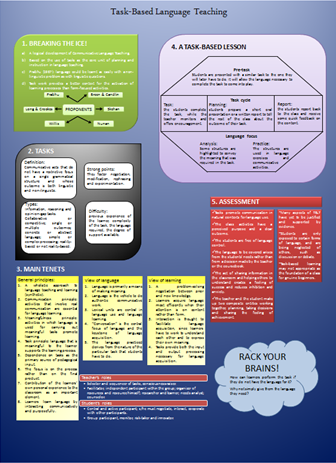

A necessary starting point in developing ICT competence is computer or technological literacy, which involves the skills necessary to use a computer and its applications and the capacity to adapt to new tools as they become available. In this sense, there is an increasingly consensual view in the specialized literature (Dudeney, 2011; O’Dowd, 2007; Ware, 2009) that students as not as technology-savvy as Prensky (2001) would have it. The digital immigrant/digital native divide is in fact being superseded by the digital visitor/digital resident dichotomy (Dudeney, 2011), which reflects the increasingly widespread view that students’ technological literacy is more limited or patchy than it might seem at first blush, and that a gap may exist between their everyday online practices and the online literacies required to function effectively in foreign language learning scenarios. In this sense, explicitly familiarizing students with simple authoring tools and web 2.0 applications helps push them from being tech-comfy (having the computer literacy to use a digital tools for everyday social and entertainment purposes) to being tech-savvy (being able to use key tools for educational and professional purposes) (Pegrum, 2009). We strive to do this by teaching them how to use Word to fine-tune their writing (through the DDL project); PowerPoint to draw up a poster on a language teaching method which they then have to present at a real pedagogical innovation conference held within the Master’s (via the INNOFIL project – cf. Figure 1); or how to use the ILIAS virtual learning environment adequately in order to download materials, complete activities, take online tests, or participate on the forum or chat (by means of the VLE project).

Figure 1. Sample poster drawn up using PowerPoint

The mastery of these basic tools allows us to proceed to the development of what is perhaps the most important type of digital literacy within the EHEA: information, search, filtering, or critical literacy. The latter entails the ability to locate, evaluate, compare, and use the practically limitless amount of information available on the Internet. Contrary to the traditionalist stance which sees teaching as transmission of knowledge and learning as reproduction of contents (Pérez Gómez et al., 2009c), post-secondary teaching is now held to be concerned with equipping learners with the tools they need to find, select, use, and interpret the vast amount of data they have within their reach (Pérez Gómez et al., 2009a). Through the development of this literacy, rote memorization yields prominence to self-directed learning, where teachers pull back from being donors of knowledge in a passive learning context to become facilitators in a student-led scenario fully in keeping with the underpinnings of the Bologna process. In our context, students are familiarized with the use of the web as corpus or the BNC online service (within the DDL project), and with the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) for them to carry out a critical appraisal of language teaching journals and to foster lifelong learning in this arena (as part of the INNOFIL project – cf. Figure 2 for sample activity).

| SEMINAR 1: USING BIBLIOGRAPHICAL RESOURCES

This initial seminar will provide an approximation to the bibliographical resources you have within your reach to work on the subject of “Aprendizaje y enseñanza I”.

We’re going to be working with the following addresses:

This initial seminar will be structured in three main phases:

The ultimate aim of this seminar is to show you exactly where you can access the main bibliographical resources you will need for this subject and for your future career as English teachers, so that you can always keep up-to-date with the latest goings-on in our profession. Never forget that it’s crucial for us as English teachers -perhaps more so than in any other teaching profession- to be up to speed with the language we teach and with the best ways to do so. |

Figure 2. Sample activity used to work on critical literacy

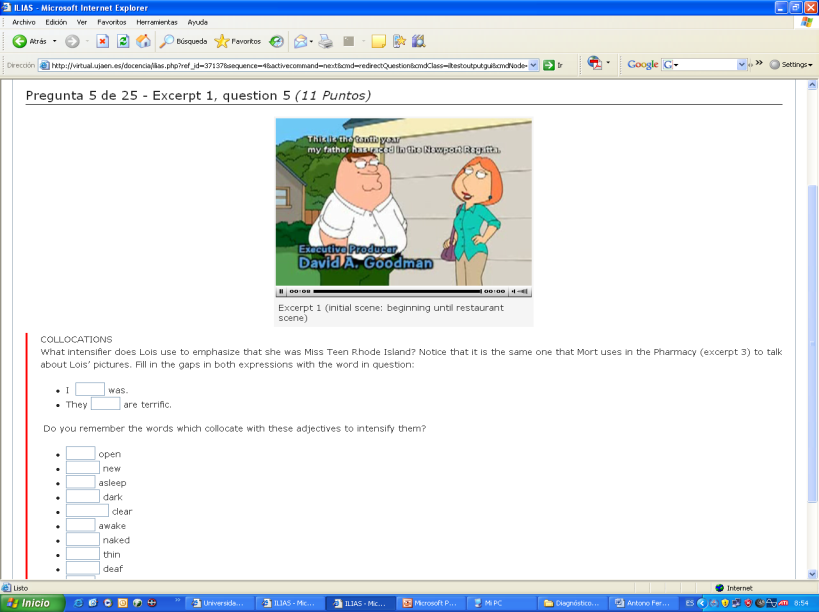

A third type of digital literacy which needs to be developed affects the ability to incorporate different types of multimedia – pictures, audio, movies – as part of a text. In this sense, we not only have our learners work with Internet texts, but also with podcasts, vodcasts, or commercials from YouTube (in the INNOFIL project), and with TV series and sitcoms (through the VLE project – cf. Figure 3), multimodal elements they are also expected to introduce into their own presentations within in-site tuition hours.

Figure 3. Screenshot of a VLE project activity

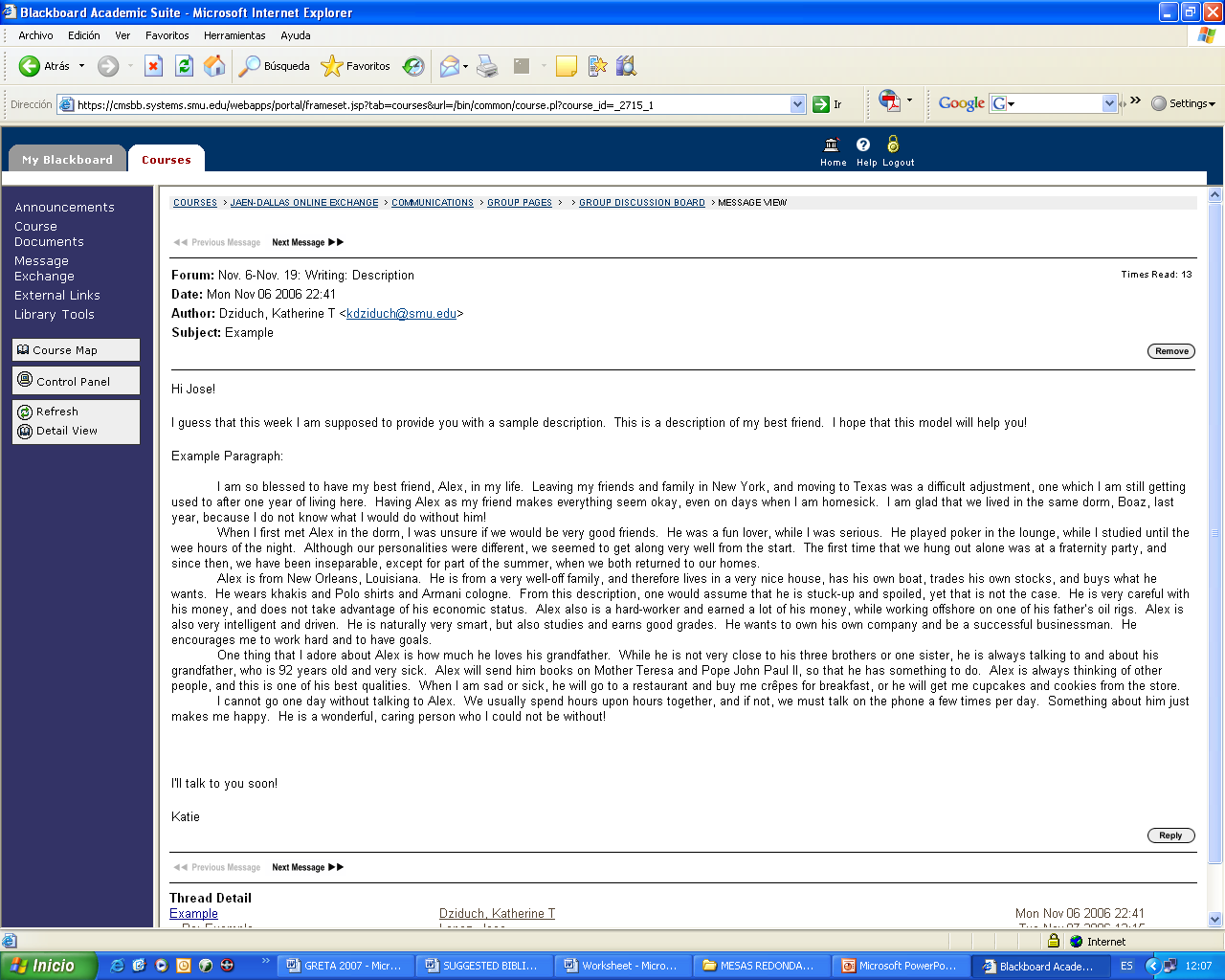

Computer-mediated communication and intercultural literacy are primarily worked on through the telecollaboration project, which allows students to write and understand effectively online communication, including knowledge of netiquette and rules of politeness, and to interact effectively with conversation partners from differing cultural backgrounds (cf. Figure 4 for a sample interaction via the Blackboard platform).

Figure 4. Screenshot of the Blackboard platform

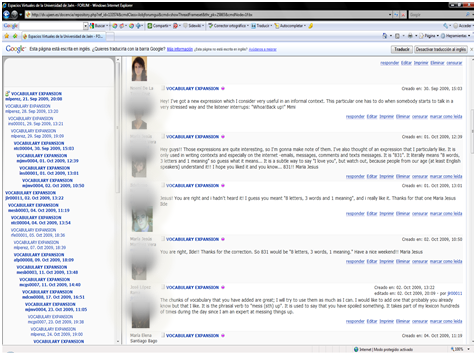

Finally, it becomes increasingly paramount to foster our students’ understanding of how to present themselves on the web, how to contribute to social networking and sharing sites, and how to leverage social and professional networks to stay abreast of key information. This is attained via personal, participatory, and network literacy, which we promote by broadcasting conferences on the professional community of practice we have created on Facebook, by giving visibility to student projects through a blog we have set up within our Master’s, or by encouraging them to liaise through a forum and wiki in order to carry out group tasks (cf. Figure 5 for a screenshot of the vocabulary expansion forum within the INNOFIL project).

Figure 5. Screenshot of the vocabulary expansion forum

RESULTS AND CONCLUSION

In order to redress the lacuna evinced by EHEA research regarding the insufficient development of ICT competence and given the manifold assets its explicit incorporation has in Bologna-adapted language degrees, for well over half a decade, we have been working on the different components of this competence via five different pedagogical innovation projects. Has this increased effort and workload on our part been worthwhile? The quantitative and qualitative studies which have accompanied our projects allow us to respond to this final query.

The development of ICT competence has, to begin with, allowed us to improve the learning process. The quasi-experimental studies within the DDL, VLE, and podcasting projects have invariably yielded significantly superior outcomes for the experimental group, which has outstripped its control counterpart on the writing and vocabulary aspects considered on the post-tests administered (cf. Pérez Cañado & Díez Bedmar, 2006; Pérez Cañado, 2010b; and Torralbo Jover, 2008, respectively, for the specific outcomes).

There has also been an increase in the satisfaction and motivation of the participating cohorts. The qualitative questionnaires which have accompanied the telecollaboration or VLE projects have always received mean scores well over 3 on a 4-point Likert-type scale, with the most highly ranked item being the student’s desire to participate in projects of this nature in the future (cf. Pérez Cañado & Ware, 2009 and Pérez Cañado, 2010b for the detailed results).

All this has been attained whilst favoring a new teaching style on the part of the lecturers involved. In this sense, the use of ICT competence has enabled us to have continued contact with the students beyond class hours via the forum or chat; to hold online tutorials for problem resolution with greater flexibility; to monitor group work, ascertaining who is participating and who is loafing, something to which the teacher would not be privy using traditional methods of communication; to give visibility to the final outcomes of the diverse tasks carried out by the learners (e.g. podcasts, pecha kuchas, or PowerPoints); to foster greater autonomy, independence, and lifelong learning via the web-based resources made available; to further practice and reinforce each topic covered through online tests and activities, which provide immediate feedback and enable us to track who has completed them; or to create a community of learning where everyone can work collaboratively to create a final outcome (e.g. a wiki or an updated vocabulary repository) and help classmates with doubt resolution. All this could not be as easily achieved via traditional in-site tuition, so that the use e-learning technologies has allowed us , as Christensen, Aaron, and Clark (2002: 32) put it, to “do more effectively what [we] are already trying to do”.

Finally, the development of digital competence has also helped us approximate the pedagogical rationale underlying the EHEA, especially in terms of competence development. Through ICT competence, we have also explicitly worked on other core generic and specific competencies which have been included in our new English Studies degree at the University of Jaén. To cite an example, our five projects have concomitantly developed instrumental mastery of the English language (competence E1), learner autonomy (competence G7), critical thinking (competence G5), or the capacity to design and manage projects, reports, presentations, and papers (competence G11).

Thus, in the light of these findings, the use of technology should not be seen, as Kessler and Ware (2012: in press) put it, “as a separate competency, but rather as a vehicle for accomplishing other tasks”. Whether we like it or not, ICT competence is here to stay, and its role is becoming increasingly significant in our HE system: “If our university and state universities in general are to remain at the forefront in teaching and research in the future, we have to make sure that we implement ICT as effectively as possible in the new degree and postgraduate degree structures” (Pennock-Speck, 2009: 183-184). Until now, it certainly appears to be providing a unique opportunity to revise and update HE methodology and to reinvigorate English language teaching.

REFERENCES

Alcantud Díaz, A. (2010). El relato digital educativo como herramienta de incorporación de las nuevas tecnologías a la educación superior: una experiencia práctica en Filología Inglesa. Lenguaje y Textos, 31, 35-47.

Benito, A., & Cruz, A. (2007). Nuevas claves para la docencia universitaria en el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior. Madrid: Narcea.

Blanco, A. (Coord.). (2009). Desarrollo y evaluación de competencias en educación superior. Madrid: Narcea.

Brantmeier, C. (2008). Meeting the demands: the circularity of remodeling collegiate foreign language programs. The Modern Language Journal, 92(2), 306-309.

Brígido Corachán, A. M. (2008). Collaborative e-learning in the European Higher Education Area (EHEA): Towards a peer-assisted construction of knowledge. GRETA. Revista para Profesores de Inglés, 16, 14-18.

Brown, J. D. (2001). Using surveys in language programs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bueno González, A. et al. (2008). Informe de la Red CIDUA de la Licenciatura de Filología Inglesa. Universidades Andaluzas.

Cano García, M. E. (2008). La evaluación por competencias en la educación superior. Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado, 12. Retrieved from http://www.ugr.es/local/recfpro/rev123COL1.pdf

Ceballos Muñoz, A. (2010). Tutorías electrónicas transversales: una manera innovadora de acompañar a los estudiantes de las titulaciones de idiomas. Lenguaje y Textos, 31, 49-59.

Christensen, C., Aaron, S., & Clark, W. (2002). Disruption in education. In M. Devlin, R. Larson, & J. Meyerson (Eds.), The internet and the university: Forum 2001.Retrieved from https://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ffpiu013.pdf

CIDUA. (2005). Informe sobre la Innovación de la Docencia en las Universidades Andaluzas. Sevilla: Consejería de Ecuación, Junta de Andalucía. Retrieved from http://www.uca.es/web/estudios/innovacion/ficheros/informeinnovacinjuntaabril2005.doc .

Dudeney, G. (2011, March). New literacies, teachers, and learners. Paper presented at the 34th TESOL-Spain Convention: Changes and Challenges: Expanding Horizons in ELT, Madrid.

European Ministers of Education. (1999). The Bologna Declaration. Retrieved from http://www.bologna-bergen2005.no/Docs/00-Main_doc/990719BOLOGNA_DECLARATION.PDF

European Ministers Responsible for Higher Education. (2003). Realising the European Higher Education Area. Communiqué of the Conference of Ministers responsible for Higher Education in Berlin on 19th September 2003. Retrieved from http://www.eua. be/fileadmin/user_upload/files/EUA1_documents/OFFDOC_BP_Berlin_communique_final.1066741468366.pdf

European Ministers Responsible for Higher Education. (2005). Achieving the Goals. Communiqué of the Conference of European Ministers Responsible for Higher Education. Bergen, 19-20 May 2005. Retrieved from http://www.bologna-bergen2005.no/Docs/00-Main_doc/050520_Bergen_Communique.pdf

European Ministers Responsible for Higher Education. (2009). Leuven Communiqué. The Bologna Process 2020 – The European Higher Education Area in the new decade. Retrieved from http://www.ond.vlaanderen.be/hogeronderwijs/bologna/conference/documents/leuven_louvain-la-neuve_communiqu%C3%A9_april_2009.pdf

European University Association. (2003). Graz Declaration – Forward from Berlin: The Role of Universities. Retrieved from http://www.eua.be/f ileadmin/user_upload/files/EUA1_documents/COM_PUB_Graz_publication_final.1069326105539.pdf

European University Association. (2005). Glasgow Declaration – Strong Universities for a Strong Europe. Retrieved from http://www.eua.be/ fileadmin/user_upload/files/EUA1_documents/Glasgow_Declaration.1114612714258.pdf

European University Association. (2010). Budapest-Vienna Declaration on the European Higher Education Area. Retrieved from http://www.ond.vlaanderen.be/hogeronderwijs/bologna/2010_conference/documents/Budapest-Vienna_Declaration.pdf

Green, M., Eckel, P., & Barblan, A. (2002). The brave new (and smaller) world of higher education: A transatlantic view. Retrieved from http://www.eua.be/fileadmin/user_upload/files/EUA1_ documents/brave-new-world.1069322743534.pdf

Gregori-Signes, C. (2008). Integrating the old and the new: Digital storytelling in the EFL language classroom. GRETA. Revista para Profesores de Inglés, 16, 43-49.

Gregori-Signes, C., & Pennock-Speck, B. (2007). Cursos de lectura online: Actitud del estudiante universitario frente a las innovaciones tecnológicas. In M. Losada Friend, P. Ron Vaz, S. Hernández Santano, & J. Casanova García (Eds.), Proceedings of the 30th International AEDEAN Conference (CD-ROM). Huelva: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Huelva.

Jordano de la Torre, M. (2008). Propuesta para la práctica y evaluación de la competencia oral en los estudios de Turismo a distancia de acuerdo con el EEES. GRETA. Revista para Profesores de Inglés, 16, 50-57.

Kessler, G., & Ware, P. D. (In press for 2012). Addressing the language classroom competencies of the European Higher Education Area through the use of technology. In M. L. Pérez Cañado (Ed.), Competency-based language teaching in higher education (in press). Amsterdam: Springer.

Levy, M., & Hubbard, H. (2005). Why call CALL “CALL”? Computer Assisted Language Learning, 18(3), 143-149.

Ma, W. (2008). The University of California at Berkeley: An emerging global research university. Higher Education Policy, 21, 65-81.

Madrid Fernández, D., & Hughes, S. (2009). The implementation of the European credit in initial foreign language teacher training. In M. L. Pérez Cañado (Ed.), English language teaching in the european credit transfer system: Facing the challenge (pp. 227-244). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Nieto García, J. M. (2007). Sobre convergencia y uniformidad: La licenciatura en Filología Inglesa desde la perspectiva de un coordinador de titulación. In Actas de las II Jornadas de trabajo sobre experiencias piloto de implantación del crédito europeo en las universidades andaluzas (actas en CD). Granada: Universidad de Granada.

O’Dowd, R. (2007). Foreign language education and the rise of on-line communication: A review of promises and realties. In R. O’Dowd (Ed.), Online intercultural exchange (pp. 17-40). Exeter: Multilingual Matters.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2005). Definition and selection of competencies: Theoretical and conceptual foundations (DeSeCo). Summary of the Final Report. Retrieved from http://www.portal-stat.admin.ch/deseco/deseco_final report_summary.pdf

Pegrum, M. (2009). From blogs to bombs. The future of digital technologies in education. Crawley: UWA Publishing.

Pennock-Speck, B. (2009). European convergence and the role of ICT in English Studies at the Universitat de València: Lessons learned and prospects for the future. In M. L. Pérez Cañado (Ed.), English language teaching in the European Credit Transfer System: Facing the challenge (pp. 169-185). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Pennock-Speck, B. (In press for 2012). Teaching competences through ICTs in an English degree programme in a Spanish setting. In M. L. Pérez Cañado (Ed.), Competency-based language teaching in higher education (in press). Amsterdam: Springer.

Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2010a). Globalization in foreign language teaching: establishing transatlantic links in higher education. Higher Education Quarterly, 64(4), 392-412.

Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2010b). Using VLE and CMC to enhance the lexical competence of pre-service English teachers: A quantitative and qualitative study. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 23(2), 129-152.

Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2011a). The use of ICT in the European Higher Education Area: Acting upon the evidence. In F. Suau-Jiménez, & B. Pennock-Speck (eds.), Interdisciplinarity and languages. Current issues in research, teaching, professional applications and ICT (pp. 21-43). Frankfurt-am-Main: Peter Lang.

Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2011b). El desarrollo de competencias comunicativas a través de seminarios transversales ECTS: Una experiencia en la Universidad de Jaén. Teoría de la Educación: Educación y Cultura en la Sociedad de la Información, 12(1), 294-319.

Pérez Cañado, M. L., & Díez Bedmar, M. B. (2006). Data-driven learning and awareness-raising: An effective tandem to improve grammar in written composition? iJET: International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 1(1), 1-11.

Pérez Cañado, M. L., & Ware, P. D. (2009). Why CMC and VLE are especially suited to the ECTS: The case of telecollaboration in English Studies. In M. L. Pérez Cañado (Ed.), English language teaching in the European Credit Transfer System: Facing the challenge (pp. 111-150). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Pérez Gómez, A., Soto Gómez, E., Sola Fernández, M., & Serván Núñez, M. J. (2009a). La universidad del aprendizaje: Orientaciones para el estudiante. Madrid: Ediciones Akal, S.A.

Pérez Gómez, A., Soto Gómez, E., Sola Fernández, M., & Serván Núñez, M. J. (2009b). Aprender en la universidad. El sentido del cambio en el EEES. Madrid: Ediciones Akal, S.A.

Pérez Gómez, A., Soto Gómez, E., Sola Fernández, M., & Serván Núñez, M. J. (2009c). Los títulos universitarios y las competencias fundamentales: Los tres ciclos. Madrid: Ediciones Akal, S.A.

Pérez Gómez, A., Soto Gómez, E., Sola Fernández, M., & Serván Núñez, M. J. (2009d). Orientar el desarrollo de competencias y enseñar cómo aprender. La tarea del docente. Madrid: Ediciones Akal, S.A.

Pérez Gómez, A., Soto Gómez, E., Sola Fernández, M., & Serván Núñez, M. J. (2009e). Contextos y recursos para el aprendizaje relevante en la universidad. Madrid: Ediciones Akal, S.A.

Poblete Ruiz, M. (2006). Las competencias, instrumento para un cambio de paradigma. In M. P. Bolea Catalán, M. Moreno Moreno, M. J. González López (eds.), Investigación en educación matemática: Actas del X Simposio de la Sociedad Española de Investigación en Educación Matemática (pp. 83-106). Zaragoza: Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses y Universidad de Zaragoza.

Poblete Ruiz, M. (2008, December). Cuestiones clave en torno a la formación basada en competencias. Plenary conferenceted at the II Jornadas Internacionales UPM sobre Innovación Educativa y Convergencia Europea 2008, Madrid.

Pratt, M. L., Geisler, M., Kramsch, C., McGinnis, S., Patrikis, P., Ryding, K., & Saussy, H. 2008. Transforming college and university foreign language departments. The Modern Language Journal, 92(2), 287-292.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5), Retrieved from http://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

Ron Vaz, P., Fernández Sánchez, E., & Nieto García, J. M. (2006). Algunas reflexiones sobre la aplicación del crédito europeo en la Licenciatura de Filología Inglesa en las universidades de Andalucía (Córdoba, Huelva y Jaén). In Actas de las I Jornadas de trabajo sobre experiencias piloto de implantación del crédito europeo en las universidades andaluzas (actas en CD). Cádiz: Universidad de Cádiz.

Shetzer, H., & Warschauer, M. (2000). An electronic literacy approach to network-based language teaching. In M. Warschauer, & R. Kern (eds.), Network-based language teaching: Concepts and practice (pp. 171–185). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Terrón López, M. J., & García García, M. J. (In press for 2012). Assessing transferable generic skills in language degrees. In M. L. Pérez Cañado (Ed.), Competency-based language teaching in higher education (in press). Amsterdam: Springer.

Torralbo Jover, M. (2008). Las nuevas tecnologías en el ECTS: El desarrollo de la competencia léxica en inglés a través de los podcasts. GRETA. Revista para Profesores de Inglés, 16, 71-77.

Tudor, I. (2008). The language challenge for higher education institutions in Europe, and the specific case of CLIL. In J. Martí i Castell, & J. M. Mestres i Serra (eds.), El multilingüisme a les universitats en l’Espai Europeu d’Educació Superior (actes del seminari del CUIMPB-CEL 2007) (pp. 41-64). Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans.

Ware, P. D. (2009, February). Critical issues in telecollaborative task design. Invited talk within the University of Jaén ECTS Seminar Program, Jaén.

Ware, P. D., & Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2007). Grammar and feedback: Turning to language form in telecollaboration. In R. O’Dowd (ed.), online intercultural exchange (pp. 107-126). Exeter: Multilingual Matters.

Zaragoza Ninet, M. G., & Clavel Arroitia, B. (2008). ICT implementation in English Language and English Dialectology. GRETA. Revista para Profesores de Inglés, 16, 78-84.

Zaragoza Ninet, M. G., & Clavel Arroitia, B. (2010). La enseñanza del inglés a través de una metodología blended-learning: Cómo mejorar el método tradicional. Lenguaje y Textos, 31, 25-34.

This academic article was accepted for publication after a double-blind peer review involving four independent members of the Reviewer Board of Int. HETL Review, and three subsequent revision cycles. Receiving Associate Editor: Dr António Teixeira, Universidade Aberta, Portugal, member of the International HETL Review Editorial Board.

Suggested Citation:

Pérez Cañado, M. L. (2013). The Development of ICT Competence within Bologna-Adapted Language Degrees. The International HETL Review. Volume 3, Article 1, https://www.hetl.org/academic-articles/the-development-of-ict-competence-within-bologna-adapted-language-degrees

Copyright © [2013] María Luisa Pérez Cañado

The author(s) assert their right to be named as the sole author(s) of this article and the right to be granted copyright privileges related to the article without infringing on any third-party rights including copyright. The author(s) retain their intellectual property rights related to the article. The author(s) assign to HETL Portal and to educational non-profit institutions a non-exclusive license to use this article for personal use and in courses of instruction provided that the article is used in full and this copyright statement is reproduced. The author(s) also grant a non-exclusive license to HETL Portal to publish this article in full on the World Wide Web (prime sites and mirrors) and in electronic and/or printed form within the HETL Review. Any other usage is prohibited without the express permission of the author(s).

Disclaimer

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and as such do not necessarily represent the position(s) of other professionals or any institution.