HETL Note:

In this academic article, author Dr. Rocío Aliaga-Isla discusses how doctoral education in Spain has changed over the past, especially since Spain’s inclusion into the European Union. The author conducted an extensive review of Spain’s PhD education policies over the years and frames her analysis through the lens of institutional theory.

Author Bio:

Rocío Aliaga-Isla holds the International PhD in Entrepreneurship and Business Management at Business Economics Department at Autonomous University of Barcelona. Her PhD research was in the field of entrepreneurship focusing specially on immigrant entrepreneurs who are settled in Spain. Part of her research was developed at the International Research Institute – IRI at the Ted Rogers School of Management in Toronto. Other research explores the impact of the human capital on the perception of entrepreneurial opportunities. In addition to entrepreneurship she also researches on higher education focusing specially in PhD education and its evolution in the last years. The outcomes of her research have been published in several academic journals, books and chapter books.

Rocío Aliaga-Isla holds the International PhD in Entrepreneurship and Business Management at Business Economics Department at Autonomous University of Barcelona. Her PhD research was in the field of entrepreneurship focusing specially on immigrant entrepreneurs who are settled in Spain. Part of her research was developed at the International Research Institute – IRI at the Ted Rogers School of Management in Toronto. Other research explores the impact of the human capital on the perception of entrepreneurial opportunities. In addition to entrepreneurship she also researches on higher education focusing specially in PhD education and its evolution in the last years. The outcomes of her research have been published in several academic journals, books and chapter books.

Furthermore, Rocio holds a M.Sc. in Social Policy at University of Brasilia in Brazil. Her thesis focused on the prevention of the HIV/Aids among youth people. Then, the education and health policies were considered in her work. Her experience allowed her to work at the UNESCO in Brasilia as a consultant. Moreover, Rocío has worked as Research Analyst at the SEFORIS project under the FP7 of the European Union Research, specifically for the WP3. Currently, she takes a Marie Curie COFUND to research at the Centre d’Economie Sociale at the HEC Liege Management School at the Liege University. Dr. Aliaga-Isla may be contacted at [email protected].

The Evolution of PhD Education in Spain: A Chronological Review of Supra-national and National Actions

Rocío Aliaga-Isla

Liege University, Belgium

Abstract

PhD education in Spain has changed; the current conception of the PhD is different from its initial concept. PhD education policy in Spain has experienced changes in its objectives and structure. Since its membership into the European Community, institutional policies at supra-national and national level have shaped and conditioned such changes. Therefore, how have PhD education policies changed over a long time in Spain? To answer this question, a chronological review has been conducted under the light of institutional theory. Several legal documents enacted at supra-national level are reviewed to frame the changes of PhD education policy at a national level. Moreover, national legal documents are reviewed to follow the evolution of PhD education in Spain. This study shows that PhD education in Spain has experienced rapid changes, which are congruent to some extent with the supra-national policies that have emerged from the social and economic change in the European Union.

Keywords: PhD education, institutional approach, supra-national and national documents, policy, chronological review

Introduction

In the last decades, PhD education policy (and training) has become an important point in the political agenda in the European Union. Currently, several institutional changes have occurred at several levels in order to improve PhD education in Europe. The Bologna Declaration of 1999 – with the aim to create the European Higher Education Area – and the Lisbon Strategy of 2000 – that formulated the creation of the European Research and Innovation Area – have guided the changes of PhD education in Europe (Kehm, 2006). The main objective of these actions was to harmonize the higher education with the aim to create the most dynamic and competitive knowledge-based economy in the world by 2010 (Capano & Piattoni, 2011). To accomplish these objectives, several actions have been taken by the higher education supra-national institutions involved in this complex process. This implies the division of tasks and responsibilities among the European Union and the member states. Therefore, a new governance structure based on a partnership approach between the higher education institutions in the European Union and the member states was put into place.

The Spanish higher education system in general has experienced major changes in recent years. There are historical facts that have triggered such changes, such as the membership of Spain into the European Community in 1986. It is clear that the membership of Spain into the European area has changed several issues regarding a common purpose, the development of the Euro zone. Within this context, therefore, Spain as a signatory country of the Bologna process is experiencing several institutional changes in its PhD education policy. Thereby, the definition of PhD education is different from its initial concept (Noble, 1994; Clark, 1995). Several higher education guidelines enacted at supra-national level have shaped PhD education at a national level. Therefore, the objectives and the structure of PhD education in Spain have changed, being consistent with the purposes established by the higher education institutions at supra-national level (Canal-Domínguez & Muñiz-Pérez, 2012).

This study examines the changes in PhD education policy in Spain under the light of the institutional theory (Greenwood, Oliver, & Suddabi, 2008). This framework is appropriate to conduct the review of changes in political issues, such in the case of PhD education policy in Spain. Therefore, the research general question that guides the development of this study is: How has PhD education policy changed over time in Spain? Also, three sub questions are considered for this study: How have supra-national policies of the European Union specifically influenced the changes in PhD education policy in Spain? What Spanish policies have governed PhD education over time? How has Spain’s PhD, in practice, changed over time as a result of those policies?

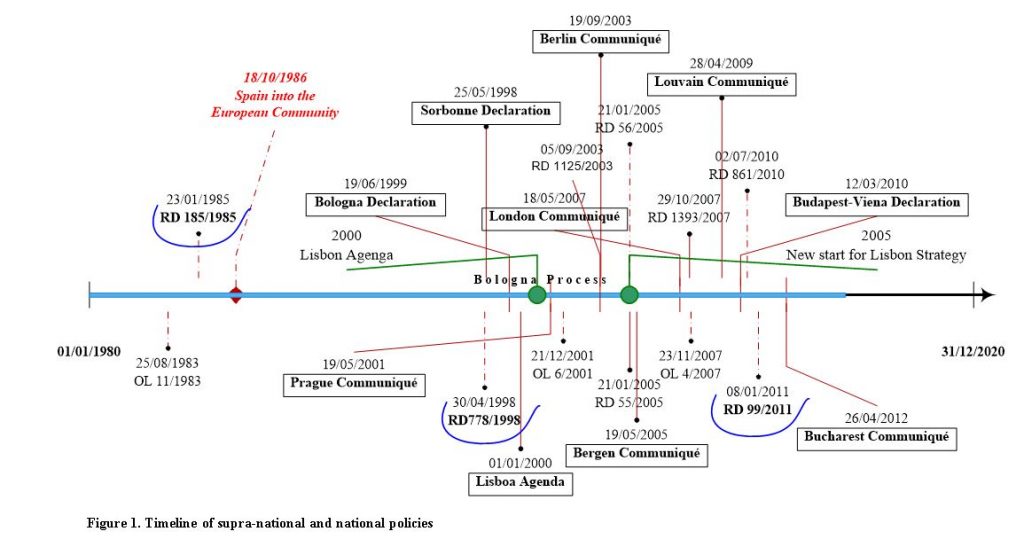

To answer these questions, this study first reviewed several supra-national documents from the various ministerial meetings to understand the changes in a member state, Spain. It was focused on the Sorbonne Declaration, Bologna Declaration, Lisbon Agenda, Prague Communiqué, Berlin Communiqué, Bergen Communiqué, London Communiqué, Louvain Communiqué, Budapest-Vienna Declaration and the Bucharest Communiqué. And second, at national level, several policies are reviewed, focusing specifically on three main Royal Decrees that have governed PhD education in Spain. Figure 1 shows a timeline of the supra-national and national policies that have been chronologically reviewed.

The findings showed that supra-national policies have played a role in the changes of PhD education policy in Spain. Moreover, PhD education policy in Spain has changed in its objectives, as well as in its structure. For instance, the objectives highlighted in the Royal Decrees 185/1985 and 778/1998 are similar. The RD 185/1985 was enacted one year before the membership of Spain into the European Community. Therefore, the RD 185/1985 governed PhD education, considering Spain as a single country. In contrast, the RD 778/1998 was enacted in the already-established European Union, despite the higher education issue was not relevant. This means that the objectives pointed out in this RD are similar to the previous RD 185/1985. Nonetheless, clearly changes are stated with the RD 99/2011, where the research activity recovers extreme importance to develop high quality scientific research. Thereby, PhD education should be developed in the intersection of the European Higher Education Areas (EHEA) and the European Research Area (ERA), which will be the pillars of the knowledge society in Europe. As a consequence, the structure of the PhD has changed according stipulations in the respective royal decrees.

This study contributes by making a state-of-the-art Spanish PhD education policy trajectory that shows how the supra-national and national policies have guided this path. Therefore, to understand, the policies that guide the implementation help us to wider visualize the changes in PhD education policy in Spain over time. Also, the contribution relies on the claim of some authors that highlighted a lack of studies about PhD education in Spain (Mora, Garcia-Montalvo, & Garcia-Aracil, 2000; Moral & Vidal, 2000; Sánchez, 1996), so this is a great endeavor to contribute toward filling this gap.

The remained of the paper is organized as follows. The next section is dedicated to frame the institutional theory and its importance to understanding the changes in PhD education policy. The following section presents the methodology. Then the presentation of the findings followed by the discussion and conclusion.

Theoretical approach

Institutional Theory: Looking at the Supra-national and National Levels

There is a consensus among social scientists that institutions matter for understanding the environmental changes over time and space (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; March & Olsen, 1996; North, 1990; Powell & DiMaggio, 1991). Moreover, there are several branches of institutional theories in different fields of knowledge, such as economic, sociology and political science (Scott, 2008). Thereby, changes in higher education, specifically in PhD education policy in Spain, are related to organizations’ openness to their social and cultural environments (Scott, 1992). Then, these changes are legitimated by the enactment of various legal documents and policies.

Moreover, the political system can be interpreted as functioning based on a mix of principles (March & Olsen, 2005). For instance, changes in PhD education policy are not only related to the ambitious objective to reach a high quality of education, but it is also intrinsically related to the economy of the country. Furthermore, as PhD education policy is extremely related to research, then research is also related to the economy. In this sense, the education policy enacted by supra-national institutions is responsible for the changes in the national PhD education; thereby, it is related to political institutions that are organizations that create, enforce and apply laws. For instance, the objective of Lisbon Strategy is to focus on education and research as a means to reach a sustainable economic growth in Europe (Gornitzka, 2007).

Institutional change is complicated, because it deals with the deinstitutionalization of existing rules, norms and laws to institutionalize or modify new ones, leaving new practices that could be legitimated (Olsen, 2001). Thereby, political institutions are related to normative rules that include prescriptive, evaluative and obligatory dimensions. Moreover, there are values and norms embedded in normative systems. According to Scott (2008:55) how things should be done is specified by norms that legitimate means to have valued ends; at the same time, desires and preferences are included in values, which usually are stated in the law. Thus, the institutional changes of PhD education in Spain could be understood, since the normative pillar (Scott, 2008) considering the political institutions (March and Olsen, 1996) is involved in the enactment of the higher education policies at national and supra-national levels.

In this sense, changes in PhD education in Spain are not straightforward. It involves complex processes at different levels, above all, when it is related to a member state of the European Union (EU), such as the case of Spain. This means there are institutions at supra-national level that intervene in the process of shaping PhD education policy. For instance, strictly related to PhD education in Spain are those treaties and arrangements among the EU states enacted exactly by the European Commission, the council of Ministers and the European Parliament. These political institutions are out of the Spanish borders but at the same time within the EU borders. This means that the EU has some basic features, such as a domain, which is related to the spacious-temporal of its jurisdiction; the scope is related to the extent of its decision-making power, and the procedures are related to the rules that define its various legislative institutions (Pogge, 1997). In this regard, this approach enables us to examine the trajectory of the higher education in Europe, guided by the Bologna process and the Lisbon Strategy, focusing specifically on PhD education policy in Spain.

Methodology

This study reviews the Spanish PhD education policy trajectory over time. This review relies on two main parts. The first is devoted to examining how supra-national agreements among several institutions in relation to the higher education have guided this trajectory. The legal documents included in this chronological review range from the Sorbonne Declaration in 1998 to the Bucharest Communique in 2012. The second examines several Spanish policies in relation to the higher education, focusing specifically on the three main RDs of PhD education policy, identifying which Spanish policies have governed PhD education over time and how the Spanish PhD education has changed over time as a result of those policies. The legal documents included in this examination range from 1983, with the Organic Law 11/1983, to 2011, with the Royal Decree 99/2011. Although several legal documents are reviewed, the review is centered on the three main Royal Decrees related to the Spanish PhD education policy – 185/1985, 778/1998 and 99/2011. This time span was considered, taking into account the last legal document of higher education in Spain before its membership into the European Union.

Chronological Review: The findings

Supra-National documents that shape PhD education policy in Spain

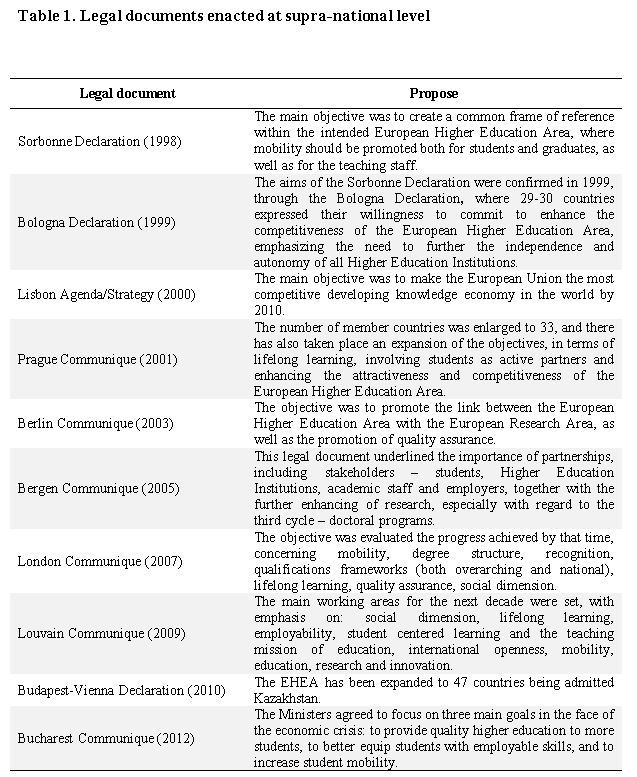

Supra-national institutions aimed for the exchange among countries involved in the process of integration, such as the case of the European Union (Sweet and Sandholtz, 1997). Europe has experienced a transformation of the higher education in the last decades. It has been influenced by two European level policy developments: the Bologna Process and the Lisbon Strategy. The Bologna Process is an intergovernmental commitment to restructuring the higher education systems, and the Lisbon Strategy is part of the Union to treat economic issues, linking them to the higher education systems (Keeling, 2006). This section presents the examination of various ministerial meetings and actions celebrated since 1998. These meetings have broadened the actions and given major precision to the tools that have been developed to achieve the objectives. These meetings are international agreements, led by supra-national institutions, such as the European Commission, the European Parliament and above all, the Council of Ministers (Balzer & Martens, 2004). Supra-national institutions are organizations with a kind of formal power at a higher level, with the aim of governing a common space (Tsebelis & Garrett, 2001). Several unified policies of the European Union have been enacted, related to the harmonization of higher education in Europe. Thereby, as it was mentioned before, although our interest is on PhD education policy, treaties and arrangements that shaped higher education in Spain are reviewed in order to contextualize. Table 1 summarizes the main legal documents that arose from the several ministerial meetings, including the Lisbon Strategy.

The topic of education was not of direct interest when the European Community was established in 1957 by the Treaty of Rome,[1] officially known as the Treaty Establishing the European Community (TEEC) (Lindberg, 1963). However, indirectly, the vocational education and training is mentioned in some articles of the Treaty of Paris, signed in 1951 and related to the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the Treaties of Rome in 1957, related to the European Economic Community (EEC) and the European Atomic Energy Committee (Euratom) (Ertl, 2006). The fragile and recent structure of the European Community has moved some important steps ahead from the economic system, regarding the education as a means to reach an economic growth. Thereby, the interest in education became clear with the increasing meetings of the education ministers and rectors of European universities.

With this aim, the Sorbonne Joint Declaration was signed in 1998 by the education ministers from France, Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom (Sorbonne Joint Declaration, 1998). The main objective of this meeting was committing themselves to harmonizing the higher education system in Europe (Marçal-Grilo, 2003). This harmonization was related to the creation of a common frame of reference within the EHEA. Thus, after the Sorbonne Joint Declaration, the Lisbon Agenda was devised in 2000, with the aim to make the European Union the most competitive developing knowledge economy in the world by 2010 (Capano & Piattoni, 2011; Gornitzka, 2007).

Higher education was not the aim of the Lisbon Agenda of 2000. According to Haskel (2009), higher education was a topic of interest some years after. Only, in February of 2005, the Commission enacted the Communication “New Start for the Lisbon Strategy” (European Commission, 2005a), and also in April of the same year, this Communication mobilized the universities in support of the Lisbon Strategy (European Commission, 2005b). Then, with the celebration of this action, the university was the focus of attention, becoming the higher education, a strategic factor in the process of the European integration (Capano & Piattoni, 2011).

Moreover, the education ministers across Europe have joined the Bologna Declaration in 1999 to address structural changes in the higher education in Europe (Bologna Declaration, 1999). Consequently, the Bologna process creates the European Higher Education Area (Keeling, 2006; van der Wende, 2000), through which the mobility of students to conduct any kind of academic activity within the European Community is facilitated. As a consequence, several ministerial meetings were conducted in order to reaffirm their commitment and assess the advancement of the process.

For instance, around one year after Bologna, the education ministers of 32 countries signed the Prague Communiqué (Prague Communiqué, 2001). The objective of this meeting was to reaffirm the commitment with the six objectives already established in the Bologna Declaration, which is summarized as follows: (1) adoption of a system of easily readable and comparable degrees, (2) adoption of a system of two main cycles, undergraduate and graduate, for higher education, (3) establishment of the European credit – ECTS, (4) overcoming obstacles to mobility, (5) promoting European cooperation in quality assurance and (6) promoting European dimensions in higher education with regard to curriculum development, inter-institutional cooperation, mobility schemes and integrated programmes of study and research (Cerych, 2002). Moreover, in this meeting, some objectives were added in relation to the lifelong learning, involving students as active partners and enhancing the attractiveness and competitiveness of the EHEA.

Furthermore, there was a necessity to evaluate the progress and establish new objectives to accelerate the construction of the EHEA. It is in this sense that the education ministers met in a Conference of Berlin (Berlin Communiqué, 2003). Ministers of education committed to ensure the link between the EHEA and the ERA to strengthen the bases of the European knowledge. The EHEA, therefore, is crucial to preserve the European richness and diversity of their cultural features but also important to foster the innovation for the social and economic development. Consistent with that, Erasmus Mundus Masters were structured, and the Commission in Bergen launched other pilot studies (Bergen Communiqué, 2005). The objective of proposing new structures in the higher education was facilitating the mobility and the recognition of degrees among the member states. Then, this is intrinsic, related to the mobility of researchers and the introduction of founding through Europe Research Council (European Commission, 2002). It is in this stage where the research is thereby valued; it is highlighted as crucial in the European Research policy and also in the Bologna processes. Moreover, in this meeting, the importance of partnerships, including the different agents involved in higher education area, above all in the doctoral programmes, were pointed out. Modernizing and investing in the quality of higher education will be an investment for the future of European citizens (European Commission, 2005b). Then, it is clear that the research policy has been added at the Bologna reforms, although they come from different policy origins. In this way, the EU research policy became consistent with the Bologna process, enhancing the political remarks of the Lisbon Strategy in education and research in Europe. Consequently, the Bologna process became a guide for universities in the member countries in the EU (Keeling, 2006).

Moreover, to strengthen the higher education system, the ministers committed themselves to elaborating the national frameworks to make the qualifications compatible with the overarching frameworks in the EHEA. The discussion about the elaboration of frameworks started with the Bergen Conference 2005, but it was really stated in the London Minister’s meeting in 2007 (London Communique, 2007). The qualification frameworks were highlighted as important instruments to achieve the comparability and transparency within the EHEA. The main objective was promoting the mobility of learners within the European Union. All the efforts for harmonizing and modernizing the European university are therefore evaluated ten years after, in the meeting of Louvain, in 2009 (Louvain Communique, 2009). Education ministers from 46 countries concluded that objectives highlighted in the Bologna process were not achieved at all (Karseth & Solbrekke, 2010). As a consequence, as it was remarked in Bologna Beyond 2010 (2009), the policies developed in the Bologna process are still valid for today, although their application at the European level will need a major commitment going beyond 2010 (Kehm, 2010).

The next Ministerial meeting was in Budapest, where education ministers met with the objective to reinforce the EHEA and also to welcome Kazakhstan as a new participant of the changes in the higher education (Budapest-Vienna Declaration, 2010). Moreover, in this declaration, ministers also agreed that more commitment is needed to reach the objectives highlighted in the Bologna process. Literally, they pointed out: “We will step up our efforts to accomplish the reforms already underway to enable students and staff to be mobile, to improve teaching and learning in higher education institutions, to enhance graduate employability, and to provide quality higher education for all” (Budapest-Vienna Declaration, 2010: 2).

It is seen that the achievements of Bologna’ objectives are also linked to the employability of graduates. This worry is more clearly seen in the Bucharest declaration, where objectives now are linked to the European economic and financial crisis (Bucharest Communiqué, 2012). Ministries of Education are aware of the economic situation and put all their efforts toward improving the quality of higher education to overcome the crisis. In this sense, their commitment is directed toward securing public funding for higher education as an investment for the future in order to reduce the youth unemployment. Thereby, three main goals are highlighted in this communique in order to face the crisis: to provide quality higher education to more students, to better equip students with employable skills and to increase student mobility (Bucharest Communique, 2012).

Considering that, education ministers pointed out new times for achieving the objectives: “For 2012-2015 it is especially concentrated on fully supporting our higher education institutions and stakeholders in their efforts to deliver meaningful changes and to further the comprehensive implementation of all Bologna action lines” (Bucharest Communique, 2012:1). Furthermore, the topic of research is touched again as explicit part of higher education in the Bucharest declaration. Thereby, ministers highlighted that research should underpin teaching and learning; this means linking the EHEA with the ERA (Bucharest Communiqué, 2012). It is in this framework that Spanish higher education is being shaped.

PhD Education Policy: the case of Spain

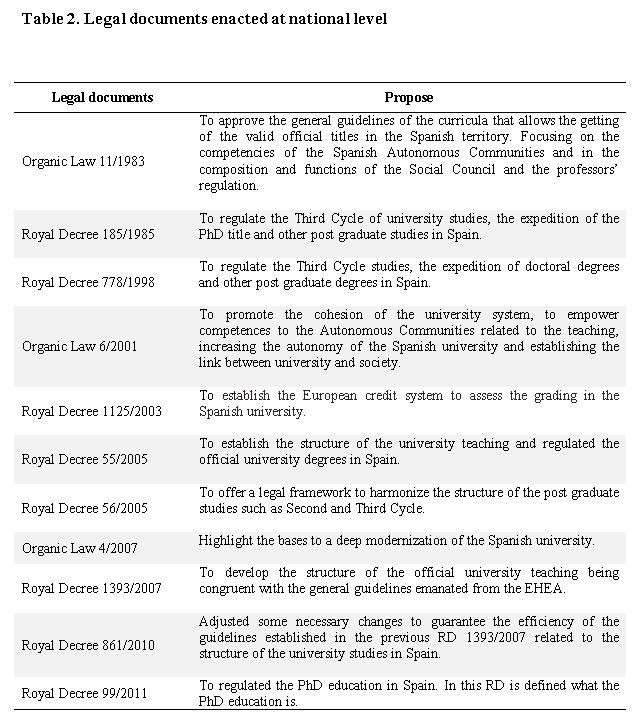

The Spanish PhD education policy has experienced changes in the last decades, due to the transformation of the higher education at supra-national level. There are particular institutional changes and historic circumstances that have shaped PhD education policy. In Spain, the Political Constitution establishes the competence of the State in the regulation to obtain academic and professional titles, as it is highlighted in the Article 149.1.30 (Constitución Española, 1978). Therefore, as Spain is part of the European Union, the transformation of the higher education at supra-national level has influenced the Spanish trajectory of PhD education policy. There are several documents that show the changes in PhD education policy, which are examined in this section, focusing specifically in the objectives and structure. Table 2 summarizes the legal documents enacted at national level. Table 3 summarizes the main changes highlighted in the three main Royal Decrees relation of PhD Education Policy in Spain.

The first law that configured the structure and governed the higher education in Spain was the Organic Law 11/1983 of August 25, related to the university reform. This law approved the general guidelines of the curricula that allow getting valid official titles in the Spanish territory (Jefatura del Estado, 1983). This law focused on the competencies of the Spanish Autonomous Communities and the composition and functions of the Social Council and the professors’ regulation. Consistent with the objectives highlighted in the Organic Law 11/1983, the regulation of the Third Cycle of university studies, the expedition of PhD title and other postgraduate studies is stipulated in the Royal Decree 185/1985 of January 23 (Education Ministry, 1985).

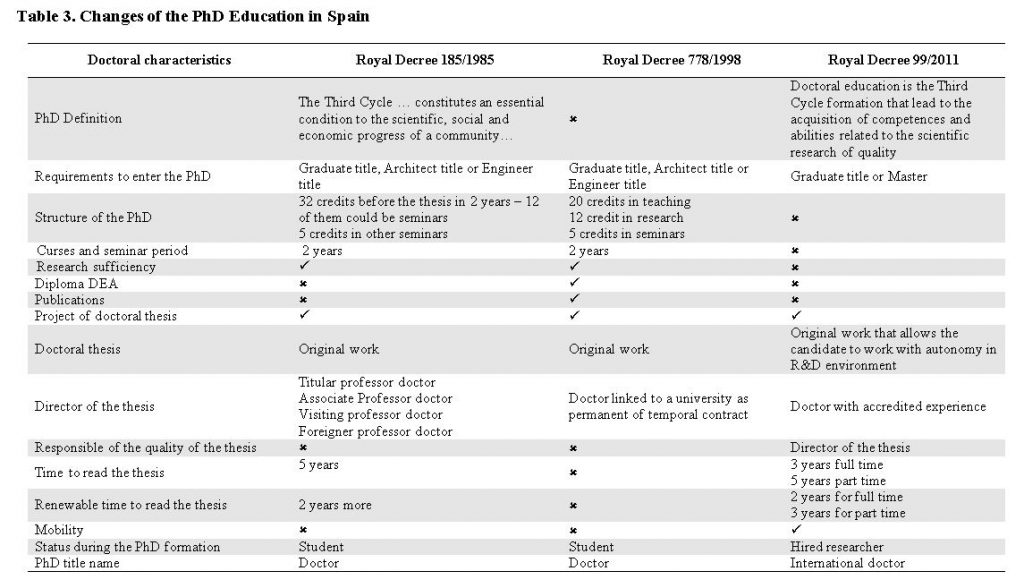

The main objective of the Royal Decree 185/1985 is to regulate the Third Cycle of university studies, the expedition of PhD title and other post-graduate studies in Spain. The RD mentioned that PhD education is important and essential to the scientific progress and for the economic and social development. In this sense, the formation of researchers is fundamental. Therefore, PhD education is important for the formation of new university professors and researchers. This RD aimed to constitute groups of research to face challenges successfully and, above all, to boost the formation of new university professors.

Regarding the structure of PhD education, the RD 185/1985 highlights that PhD education in Spain was structured, considering a period of courses and seminars, along two years. These courses and seminars have to be linked with methodology and research techniques. During the two years, the student has to reach 32 credits, from which 12 can be acquired in seminars and courses related to the field of research and up five credits from other fields of knowledge. Once the student overcomes the course work, a research-sufficiency is required. This research-sufficiency is a global evaluation about all the knowledge acquired until this stage. Moreover, a doctoral project has to be presented and supported by the supervisor. Only after that can the thesis be presented. The thesis has to be an original research work, which has to be presented during a maximum term of five years. If it is not presented in such a term, the term can be enlarged for two more years. In the case where the student’s thesis has not been approved, he/she has to leave the university and go to another university to continue with PhD education.

By the way, the RD 778/1998 still focused Spain as a single nation in practice, although the country already was a member of the European Union. In this context, the structure of PhD education was developed. PhD education structure was shaped by the Spanish Royal Decrees, in accordance with the economy and social behaviour. The main objective of the RD 778/1998 is to regulate the Third Cycle studies, the expedition of doctoral degrees and other post graduate degrees. This RD is consistent with the previous RD. In this sense, it also aimed to form new researchers, groups of research to face the challenge from new sciences and techniques. Also, it mentioned the formation of new university professors as an important factor. Moreover, in order to reach these objectives, this RD highlighted that the previous experience acquired along thirteen years in charge is taken into account to reach such objectives. In this sense, it is pointed out that programmes of quality must be the priority, as well as the inter-university programmes, interdisciplinary and the mobility of students. In order for these objectives to be effective, a minimum number of students by programme is proposed, and it is an established mechanism to plan and evaluate the quality of such programmes, considering the university autonomy (Education Ministry, 1998).

Regarding the structure, this RD declared that the total quantity of credits of the programme is divided in two main periods. Between both periods, the student has to have 32 credits. The first one is dedicated to taking some courses to obtain 20 credits. From these, fifteen credits can be awarded, taking courses and seminars in the same field of knowledge, and five credits can be joined from courses or seminars from other fields of knowledge. After that, PhD student can obtain a diploma when he/she has finished the first period, then this diploma will be recognized in any Spanish university. The second period is for researching under the supervision of a professor doctor. In this period, PhD student has to obtain twelve credits, doing research works, and in some cases, doing publications. This supervision aims for the specialization of PhD students in a determined scientific field, empowering PhD students with skills in research techniques and methodologies.

When PhD student passes the second period, a diploma of advanced studies is obtained. This diploma will be valid in any Spanish university, indicating that the PhD student has passed this period. Therefore, the possession of this diploma allows the PhD student to begin with the thesis in any Spanish university. However, the student must first present a research project that will be developed along his/her doctoral formation. Once the project is approved, the student will begin with the research, taking into consideration the originality of the topic in a specific field of knowledge. A professor that holds a PhD from a university will supervise this thesis. One or two supervisors can supervise the development of the thesis (Education Ministry, 1998).

Moreover, the RD 778/1998, in its Unique Derogatory Disposition, highlighted that in accordance with the mentioned Organic Law 11/1983 of August 25, the following legal documents are derogated: RD 185/1985 of January 23, which regulated the Third Cycle of university studies and the expedition of the PhD title; RD 1561/1985 of August 28, which modified the first final disposition of the RD 185/1985; the RD 1397/1987 of November 13, which completed the foresight of the RD 185/1985, related to the term to present the PhD thesis; the RD 537/1988 of May 27, which modified the RD 185/1985, and the RD 823/1989 of July 7, which added to the RD 185/1985 an additional disposition that recognized the PhD title of the European University Institute of Florence.

These previous legal documents described PhD education in Spain, regarding their objectives and structures. It is seen that the Royal Decrees 185/1985 and 778/1998 are similar in their objectives and also in their structure. However, the publication of research is mentioned slightly in a way as a possibility of doing that. And also, the mobility of students is highlighted in a discreet way in the RD 778/1998. Both the publication and the mobility of students are mentioned throughout this RD only once. It has been considered that, although the Royal Decree 778/1998 was developed in a context of institutional changes in Spain, the education has not been changed yet, despite the membership of Spain at the European Community, which was signed in June 12 of 1985 and entering into force on 1 January 1986.

While the first years of Spain membership into the European Community could bring changes at the economic level, the other institutional dimensions, such as the education, later took relevance in the political agendas of the European countries. As mentioned in section 3, a series of ministerial meetings and agreements among European countries occurred, aiming to ensure the standards of quality of higher education. Indeed, it has seen major changes in the Royal Decree 1125/2003 of September 5, which established the European credit system to assess the grading in the Spanish university (Education Ministry, 2003). The design of the European Higher Education Area has implied the establishment of the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS), with the aim to make learning and teaching more transparent across Europe. Moreover, the adoption of the European credit allows the recognition of all studies within the European Area. Thereby, the ECTS is closely related to the effort of modernizing the higher education in Europe to make the national systems converge.

In this context, the RD 55/2005 of January 21 established the structure of the university teaching and regulated the official university degrees in Spain. This regulation is consistent with the guidelines established in the European Higher Education Area and with the Organic Law 6/2001 of December 21 (Jefatura del Estado, 2001). Together with the RD 55/2005, the post-graduate studies are regulated by the RD 56/2005 of January 21. The university structure is modified, considering the European Higher Education Area with the aim to reach a quality in the European system, making attractive the European education at international level. The objective of the RD 56/2005 is to offer a legal framework to harmonize the structure of the post-graduate studies, such as Second and Third Cycle, which means master’s and PhD. Therefore, this RD introduced the official master title at the Spanish university system, which means to give an advanced education in research techniques (Education Ministry, 2005b).

Despite the efforts and the institutional changes highlighted in the legal documents, there has been progressive work on the harmonization of the European Higher Education Area in Spain. In doing so, the Spanish government compromised to adapt the Spanish university system into the new structure, highlighted in the Bologna declaration until 2010. To do that, the Organic Law 4/2007 of April 12 really stated the basis of a deep modernization of the Spanish university, modifying the previous Organic Law 6/2001 of December 21. The OL 6/2001 promoted the cohesion of the university system, to empower competences to the Autonomous Communities related to the teaching, increasing the autonomy of the Spanish university and establishing the link between university and society.

Despite the efforts showed in several legal documents to align the higher education to the European guidelines, the content of the OL 4/2007 remarked actions with the aim to harmonize the Spanish higher education. The rapid social changes and the pressure of the other members of the European Union to convert the Euro zone in a space of high quality research in the world influences the enactment and establishment of this OL (Jefatura del Estado, 2007). This law highlighted and emphasized the relevance of research in the university, the Title IV, in the Sections 33 and 36; the articles 38 and 39 are related to PhD education. These articles pointed out that “scientific research is the essential to teach and it is a primordial tool for the social development through the transfer of knowledge.” It is clear that the scientific research played a role in this OL. Moreover, it is mentioned that PhD education aims for the research formation, which is the milestone for teaching at the university (Education Ministry, 2007).

Consistent with the changes already highlighted, the RD 1393/2007 of October 29 has the objective to develop the structure of the official university teaching, being congruent with the general guidelines emanated from the EHEA (Education Ministry, 2007b). Chapter 1, Article 1 highlighted that the development of the structure of the official teaching university will be consistent with the European Higher Education Area and with the Organic Law 4/2007 of April 12. This RD focused on issues related to the recognition of the European credits into the Spanish university at the three levels – Degree, Master’s and PhD. The relationship between the European Higher Education Area and the European Research Area is established as a main objective in the organization of the Spanish university. In Chapter II, Article 11, issues related to the PhD in Spain are highlighted. For example, the acquirement of competences and abilities to make quality research is the new aim of PhD education.

Furthermore, Chapter V, entitled PhD Teaching, included the Article 18 PhD programme, Article 19 access to PhD Teaching, Article 20 admission to PhD teaching, Article 21 doctoral thesis, Article 22 European Mention in the PhD title and Article 23 professors in the teaching of PhD. All of them were derogated by the RD 99/2011. Even more, this RD in the Unique Derogatory Disposition highlighted that the Royal Decrees 55/2005 of January 21 and 56/2005 are derogated. As it was mentioned before, the RD 55/2005 had as objective the establishment of the official university teaching structure in Spain (Education Ministry, 2005a). Moreover, the RD 56/2005 aim regulated the postgraduate studies, which means the second and third cycle. In this changing context, the structure of university teaching in Spain highlighted in the RD 1393/2007 of October 29 is modified through the RD 861/2010 of July 2. This RD adjusted some necessary changes to guarantee the efficiency of the guidelines established in the previous RD 1393/2007, related to the structure of the university studies in Spain.

The construction of the EHEA and the EAR is a constant work; in this regard, several institutional efforts have been oriented. Therefore, PhD education will play a role in the intersection of the EHEA and the EAR, being both the pillars in a knowledge society. Likewise, it is necessary to continue to reshape and polish pieces that allow a space based on knowledge, attractive and open to the rest of the world, Europe. In this context, the RD 99/2011 regulated PhD education in Spain. Article 2 defined what PhD education is. The Third Cycle corresponds to PhD Education, which allows PhD students the acquisition of skills and abilities to develop scientific research of quality. Article 3 pointed out that the organization of PhD programmes will be established in the university statutes. PhD education lasts a maximum of three years when the student is dedicated full time. However, the duration could be up to five years when the student is dedicated partial time.

Moreover, PhD programmes do not require ECTS, because the essential activity is to research. During the PhD period, the PhD student could take some complementary formation. Once the PhD student is admitted in the PhD programme, a supervisor is assigned. The role of the supervisor is relevant in this context, so the success of research and the design of the thesis will remain on his/her expertise doing research. A research project is required in the first year of PhD education; a research commissioner will evaluate this project. If the project is approved, the PhD student can continue with the PhD. If not he/she has to modify the project, and it will be presented again at the research committee. At this time, if the project is approved, the student continues in the programme, and if not, the student has to leave the PhD programme (Education Ministry, 2011).

Furthermore, the academic commission will evaluate the PhD student yearly. And finally, the thesis will be presented. This thesis has to be an original research work in any field of knowledge. The thesis must empower the PhD student to work in an autonomous way in the R&D environment. The defence of the thesis gives the option to request the international mention in the PhD title. To obtain such mention, the student has to stay in a research centre or in an institution of higher education outside Spain for at least three months. Also, part of the thesis has to be written and presented in a different language than Spanish. The thesis has to be reviewed at minimum by two experts from an institution outside of Spain. And, a member of the tribunal of defence will be from an institution of higher education from outside Spain.

This RD is widely clear, highlighting several dimensions related with the construction of the European education area, trying to harmonize and converge in common objectives. Furthermore, it is seen that the European policy of research highlighted the necessity to promote the R&D in all social sectors through the collaboration of industry and business PhD education. This strategy will foster innovation of industry, therefore reinforcing the economy of the country (Cano, Lindon and Rebollar, 2011).

Discussion and conclusion

This article reviews chronologically several documents enacted at supra-national and national level to examine and explore the changes in PhD education in Spain. The review was conducted under the light of the institutional theory and pivoted around two main parts: The first was devoted to examine how the supra-national agreements among several institutions have guided PhD education policy changes in Spain. Second, the Spanish higher education policies are examined, focusing on the three main Royal Decrees related to PhD education policy in Spain. The RDs reviewed were the 185/1985, 778/1998 and 99/2011. However, other legal documents of the Spanish higher education were examined to contextualize the changes in PhD education policy in Spain.

The review of supra-national documents enacted by higher education institutions shows how the several ministerial summits have established the guidelines that each member of the European Union has to follow. A crucial dimension of overall European higher education policy is PhD education, which is the maximum level in the higher education structure that covers extreme importance, due to its linking with the research activity. All these efforts are consistent with the Bologna process and the Lisbon Strategy that constitutes a comprehensive basis for the European Union action in higher education. Therefore, the higher education guidelines at supra-national level have been applied at national level; such is the case of Spain.

The review of the Spanish Royal Decrees 185/1985, 778/1998 and 99/2011 shows the trajectory of the changes experienced by PhD education policy. For instance, the objectives and the structure highlighted in the RD 185/1985 focused on Spain as a single nation. Even in the RD 778/1998, Spain is still considered or treated as a single nation. This means that these RDs still were not consistent with the guidelines stipulated by the higher education institutions in the European Union. The RD 185/1985 was enacted before the membership of Spain into the European Community, so the objectives stipulated in this RD are consequent with the reality of Spain as single nation. By other way, the RD 778/1998 slightly shows some changes in respect to the previous RD. For instance, the publication and the mobility of students are found only once in this RD, and the structure had not changed at all. The division of the PhD into two periods – the teaching and the research – is highlighted. As a consequence, a diploma is delivered when finishing the teaching period and other when completed the research period.

However, the RD 99/2011 clearly highlights major changes in the objectives and structure of PhD education in Spain. For instance, the three cycles of higher education are clearly highlighted in this RD. As it was mentioned before, the RD 56/2005 modifies the structure of the higher education, considering the EHEA and the ERA. Thereby, it is under this RD that the second and third cycles are clearly divided as independent levels (Education Ministry, 2005b). Therefore, the RD 99/2011 pointed out the research activity as a main objective of PhD education, where PhD students have to acquire capabilities to deal within the international scientific community. Then, a Master’s will be a requirement to do a PhD, so the period of PhD does not have credits or teaching period, but one can take some seminars as complementary formation. The mobility of PhD students is pointed out as vital for their formation as well as to strengthen the relationship among international researchers. It is in this context where the international PhD title is given.

Therefore, again, PhD education reinforces the relationship between the EHEA and the EAR, building a pillar of knowledge society in the European Union. Moreover, the relationship of PhD education with the economic growth of Europe is an intrinsic objective, highlighted throughout the RD 99/2011. These are the current changes related to the objectives and structure of PhD education identified in the three RDs. However, it is acknowledgeable that the system is changing, and it will be changing in the future until it reaches a quasi-complete harmonization of the higher education in Europe. This harmonization is important not only for PhD education but for all the levels within the higher education in the European Union in general and in Spain in particular. Changes in PhD education are important because it will facilitate the mobility of European citizens, there will not frontiers for those to hold a recognized PhD title in Europe. All this means an impact in the economy and in the development of the research in Europe and in Spain. However, these changes also bring challenges for university administration because they have to adapt to all the changes not only in the structure of PhD education but also in ways to guide PhD students to develop a high quality research.

References

Balzer, C., & Martens, K. (2004). International higher education and the Bologna Process. What part does the European Commission play? Presented at the EpsNet Plenary Conference, Charles University, Prague.

Bergen Communiqué. (2005). The European Higher Education Area —Achieving the Goals. Communiqué of the Conference of Ministers responsible for Higher Education. Bergen, 19–20 May 2005.

Berlin Communiqué. (2003). Realizing the European Higher Education Area. Communiqué of the Conference of Ministers responsible for Higher Education. Berlin, 19 September 2003.

Bologna Beyond 2010. (2009). Background paper for the Bologna Follow-up Group prepared by the Benelux Bologna Secretariat. Leuven/Louvain-la-Neuve Ministerial Conference 28–29 April 2009.

Bologna Declaration. (1999). Joint Declaration of the European Ministers of Education. Bologna, 19 June 1999.

Bucharest Communiqué. (2012). Making the Most of Our Potential: Consolidating the European Higher Education Area. Bucharest, 26-27 April 2012.

Budapest-Vienna Declaration. (2010). On the European Higher Education Area. March 12, 2010.

Canal-Domínguez, J. F., & Muñiz Pérez, M. A. (2012). Professional doctorates and careers: The Spanish case. European Journal of Education, 47(1), 153–171.

Cano, J. L., Lindon, I., & Rebollar, R. (2011). El doctorado en Ingeniería Industrial en España. Situación actual y perspectivas. DYNA, 86(1), 29–40.

Capano, G., & Piattoni, S. (2011). From Bologna to Lisbon: The political uses of the Lisbon “script” in European higher education policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(4), 584–606.

Cerych, L. (2002). Sorbonne, Bologna, Prague: Where do we go from here? In J. Enders & O. Fulton (Eds.) Higher education in a globalizing world (pp. 121–126). Springer: Netherlands.

Clark, B. R. (1995). Places of Inquiry: Research and Advanced Education in Modern Universities. University of California Press, London, England.

Constitución Española (1978). Constitución Española.

DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Education Ministry. (1985). Real Decreto 185/1985 por el que se regula el tercer ciclo de estudios universitarios, la obtención y expedición del título de doctor.

Education Ministry. (1998). Real Decreto 778/1998, de 30 de abril, por el que se regula el tercer ciclo de estudios universitarios, la obtención y expedición del título de Doctor y otros estudios de postgrado.

Education Ministry. (2003). Real Decreto 1125/2003, de 5 de septiembre, por el que se establece el sistema europeo de créditos y el sistema de calificaciones en las titulaciones universitarias de carácter oficial y validez en todo el territorio nacional.

Education Ministry. (2005a). Real Decreto 55/2005, de 21 de enero, por el que se establece la estructura de las enseñanzas universitarias y se regulan los estudios universitarios oficiales de Grado.

Education Ministry. (2005b). Real Decreto 56/2005 por el que se regulan los estudios oficiales de postgrado.

Education Ministry. (2007). Real Decreto 1393/2007, de 29 de octubre, por el que se establece la ordenación de las enseñanzas universitarias oficiales.

Education Ministry. (2011). Real Decreto 99/2011 por el que se regulan las enseñanzas oficiales de doctorado.

Ertl, H. (2006). European Union policies in education and training: The Lisbon agenda as a turning point? Comparative Education, 42(1), 5–27.

European Commission. (2002). Higher Education and Research for the ERA: Current Trends and Challenges for the Near Future. (Brussels, Directorate-General for Research).

European Commission. (2005a). Working together for growth and jobs. A new start for the Lisbon Strategy. (COMM 24) Brussels.

European Commission. (2005b). Mobilizing the brainpower of Europe: Enabling universities to make their full contribution to the Lisbon Strategy. (COMM 152) Brussels.

Gornitzka, A. (2007). The Lisbon Process: A supranational policy perspective. In P. Maassen & J. Olsen (Eds.) University dynamics and European integration. The Netherlands: Springer.

Greenwood, R., Oliver, C., & Suddabi, K. (Eds.). (2008). The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism, UTS Library. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Haskel, B. (2009). When can a weak process generate strong results? The Bologna Process to create a European Higher Education Area. In Tömmel & Verdun (Eds.) Innovative governance. The politics of multilevel policymaking (pp. 134–157). Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Huff, A. (1990). Mapping strategic thought. Jhon Wiley & Sons.

Jefatura del Estado. (1983). Ley Orgánica 11/1983 de 25 de agosto de Reforma Universitaria.

Jefatura del Estado. (2001). Ley Orgánica 6/2001 de 21 de diciembre, de universidades.

Jefatura del Estado. (2007). Ley Orgánica 4/2007 por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 6/2001 de universidades.

Karseth, B., & Solbrekke, T. D. (2010). Qualifications frameworks: The avenue towards the convergence of European higher education? European Journal of Education, 45(4), 563–576.

Keeling, R. (2006). The Bologna Process and the Lisbon Research Agenda: the European Commission’s expanding role in higher education discourse. European Journal of Education, 41(2), 203–223.

Kehm, B. M. (2006). Doctoral education in Europe and North America: A comparative analysis. Wenner Gren International Series, 83, 67.

Kehm, B. M. (2010). The Future of the Bologna Process — The Bologna Process of the future. European Journal of Education, 45(4), 529–534.

Lindberg, L. N. (1963). The political dynamics of European economic integration. Stanford University Press, California.

London Communiqué. (2007). Towards the European Higher Education Area: responding to challenges in a globalised world. London 18 May 2007.

Louvain Communiqué. (2009). The European Higher Education Area in the new decade. Louvain, 28-29 April 2009.

Marçal-Grilo, E. (2003). European Higher Education Society. Tertiary Education and Management, 9(1), 3–11.

March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1996). Institutional perspectives on political institutions. Governance, 9(3), 247–264.

March, J., & Olsen, J. (2005). Elaborating the new institutionalism. Arena Centre for European Studies, University of Oslo.

Mora, J.G., Garcia-Montalvo, J., & Garcia-Aracil, A. (2000). Higher education and graduate employment in Spain. European Journal of Education, 35(2), 229–237.

Moral, J.-G., & Vidal, J. (2000). Adequate policies and unintended effects in Spanish higher education. Tertiary Education and Management, 6(4), 247–258.

Noble, K. A. (1994). Changing doctoral degrees: an international perspective. Society for Research into Higher Education.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, UK.

Olsen, J. (2001). Organizing European institutions of governance –A Prelude to an institutional account of political integration. In H. Wallace (Ed.) Interlocking Dimensions of European Integration. Pg. 323 – 324. Houndmills: Pelgrave.

Pogge, T. W. (1997). Creating Supra-National Institutions democratically: Reflections on the European Union’s “Democratic Deficit.” Journal of Political Philosophy, 5(2), 163–182.

Powell, W. W., & DiMaggio, P. J. (Eds.). (1991). The New institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago [etc.]: The University of Chicago Press.

Prague Communiqué. (2001). Towards the European Higher Education Area.

Sánchez, L. (1996). Políticas de reforma universitaria en España: 1983-1993. Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Ciencias Sociales.

Scott, W. R. (1992). Organizations: Rational, natural and open systems. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

Scott, W. R. (2008). Institutions and organizations (Third Edition.). Sage Publications Lt.

Sorbonne Joint Declaration. (1998). Joint declaration on harmonization of the architecture of the European higher education system. Paris, the Sorbonne.

Sweet, A. S., & Sandholtz, W. (1997). European Integration and Supranational Governance. Journal of European Public Policy, 4(3), 297–317.

Tsebelis, G., & Garrett, G. (2001). The Institutional Foundations of Intergovernmentalism and Supranationalism in the European Union. International Organization, 55(02), 357–390.

Van der Wende, M. C. (2000). The Bologna Declaration: Enhancing the transparency and competitiveness of European higher education. Higher Education in Europe, 25(3), 305–310.

This feature article was accepted for publication in the International HETL Review (IHR) after a double-blind peer review involving three independent members of the IHR Board of Reviewers and two revision cycles. Accepting editor: Charlynn Miller

Suggested citation:

Aliaga-Isla, R. (2017). The Evolution of PhD Education in Spain: A Chronological Review of Supra-national and National Actions. International HETL Review, Volume 7, Article 1, URL: https://www.hetl.org/the-evolution-of-phd-education-in-spain-a-chronological-review-of-supra-national-and-national-actions

Copyright © 2017

The author(s) assert their right to be named as the sole authors of this article and to be granted copyright privileges related to the article without infringing on any third party’s rights including copyright. The authors assign to HETL Portal and to educational non-profit institutions a non-exclusive license to use this article for personal use and in courses of instruction provided that the article is used in full and this copyright statement is reproduced. The authors also grant a non-exclusive license to HETL Portal to publish this article in full on the World Wide Web (prime sites and mirrors) and in electronic and/or printed form within the HETL Review. Any other usage is prohibited without the express permission of the authors.

Disclaimer

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors, and as such do not necessarily represent the position(s) of other professionals or any institution. By publishing this article, the authors affirm that any original research involving human participants conducted by the authors and described in the article was carried out in accordance with all relevant and appropriate ethical guidelines, policies and regulations concerning human research subjects and that where applicable a formal ethical approval was obtained.

[1] All EU treaties referred to in this paper can also be found on EUR-LEX, the portal to European Union law: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/homepage.html