HETL Note: We are proud to present the second article on the topic of democratising higher education contributed by Dr Anne Jones and Dr Lee Graham. Applying a qualitative research approach the authors investigate the dimensions of on-line democratized learning in the case of a community of teacher-learners. As a result of their analysis they propose a theoretical model that is centred on critical collaboration – the interaction between collaboration and critical thinking, driven by feelings of empowerment and facilitated by the use of social media and other information and communication technologies. The work draws on prior research and contributes to the understanding of teacher learning as a process that involves knowledge acquisition, skill development, and most importantly – the intellectual growth of the individual. The authors propose a new theory of democratized on-line learning.

Author bios:

Dr. Anne Jones is Assistant Professor of Education and Co-Director of Graduate Elementary Programs at the University of Alaska Southeast. Her research focuses on developing pre-service teacher cultural consciousness, diversity education for social justice, and technology integration for student success. Dr. Jones completed her teacher preparation at Chapman University, earned a Master’s degree in educational leadership and policy studies from California State University, Northridge and a Doctorate in education from the University of Southern California. Dr Jones be can contacted at [email protected].

Dr. Anne Jones is Assistant Professor of Education and Co-Director of Graduate Elementary Programs at the University of Alaska Southeast. Her research focuses on developing pre-service teacher cultural consciousness, diversity education for social justice, and technology integration for student success. Dr. Jones completed her teacher preparation at Chapman University, earned a Master’s degree in educational leadership and policy studies from California State University, Northridge and a Doctorate in education from the University of Southern California. Dr Jones be can contacted at [email protected].

Dr. Lee Graham is Associate Professor of Education at the University of Alaska Southeast. She gained her Ph.D. in educational technology from Mississippi State University in 1999. She presents nationally and internationally on the topic of open online environments and innovative instructional design for online learning. She is engaged in consulting to assist programs in the U.S. with the adjustment of curriculum for international audiences. Dr. Graham was awarded the Alaska Society of Technology in Education’s 2015 Technology Leadership Award. Dr Graham can be contacted at [email protected].

Dr. Lee Graham is Associate Professor of Education at the University of Alaska Southeast. She gained her Ph.D. in educational technology from Mississippi State University in 1999. She presents nationally and internationally on the topic of open online environments and innovative instructional design for online learning. She is engaged in consulting to assist programs in the U.S. with the adjustment of curriculum for international audiences. Dr. Graham was awarded the Alaska Society of Technology in Education’s 2015 Technology Leadership Award. Dr Graham can be contacted at [email protected].

Democratizing Higher Education Learning: A Case Study of Networked Classroom Research

Anne Jones and Lee Graham

University of Alaska Southeast, U.S.A.

Abstract

The case study describe and discussed in this article presents the experiences of the participants in Southeast Alaska Collaborative Classroom Research – an online open course that was the result of combining two graduate courses. Participants became the providers, as well as the consumers, of knowledge. Participants shared learning and expertise and acted as consultants and mentors to each other thereby blurring the roles of teacher and learner. We analyzed participants’ blogs, tweets, and other interactions to find examples of critical thinking, information and communications technology (ICT) competencies, collaboration, and camaraderie. As analysis continued, we realized that empowerment continued to emerge intersected with other codes. As a result, a new theory of democratized on-line learning was developed. It aims to explain the interactions between and among critical thinking, information and communication technology (ICT) competencies, collaboration, and camaraderie, and includes the concept of empowerment – the space from where the capacity to engage in democratic action emerges.

Keywords: Democratized education, networked learning, empowerment, classroom research

Introduction

This case study presented in this article explores the experience of participants in Southeast Alaska’s Collaborative Classroom Research – an open on-line course bringing together two existing courses (Impact of Technology on Student Learning, and Classroom Research). Both are graduate level courses. The Classroom Research course is required for teacher candidates who are completing their Master of Art’s degrees in teaching, and for in-service teachers completing an advanced program of study in mathematics, special education, or educational technology. The course Impact of Technology on Student Learning is required for in-service teachers or training professionals completing the Master of Education in educational technology and may be taken as an elective in the Career and Technical Education Program. All our students are e-learners, located in various locations throughout Alaska and beyond.

We created the learning space in the open using WordPress and Twitter in the hope that students would encounter a diversity of ideas and perspectives beyond those of the class enrolees. A word or phrase preceded by a hash or pound sign (#) is used in Twitter to identify messages on a specific topic. We dubbed our open learning community #seaccr (Southeast Alaska Classroom Research). In our course (Southeast Alaska Collaborative Classroom Research) #seaccr is used to designate conversations among students in the course in Twitter. We refer to the course as #seaccr throughout the remainder of this paper.

To accomplish the goals of #seaccr we needed powerful and open tools that could assist students in building a collective. Blogs and tweeting became the obvious choices. Using these two tools, students collaborated about processes and products and made revisions based on peer, rather than instructor, feedback.

Review of the Literature

Current literature addressing elements necessary for a foundation for participation in a democratic society are examined. This literature is contextualized with an eye toward developing skills necessary for work in a knowledge economy in networked environments. Participation within a collective for the purpose of ongoing skills development is posited an equalizing environment for learning in the knowledge economy. This literature forms the conceptual basis of the research.

Democracy and Education

According to Dewey (1916), education should have both a purpose for the individual student as well as a societal purpose. Therefore, educators are responsible for providing students with personally relevant learning opportunities that are immediately valuable and which ultimately enable students to contribute to society. Dewey might argue that to accomplish these goals, students ought to have same power and responsibility for their learning as their educators. In addition, a democratic experience with learning in school provides the background needed for later effective participation in a democratic society. For Dewey, students should practice communication, collaboration, and critical reflection in order to develop effective citizenship skills for a democracy (Dewey, 1916).

Cohen (2006) argues that the goals of education need to be re-framed to prioritize not only academic learning, but also social, emotional, and ethical competencies. Cohen suggests that social-emotional skills, knowledge, and dispositions are necessary for high quality of life as well as participation in a democracy. The social-emotional skills, knowledge, and dispositions for democratic participation are:

- The ability to listen to ourselves and others and the responsibility, or the inclination, to respond to others in appropriate ways.

- The ability to be critical and reflective and the appreciation of our existence as social creatures that need others to survive and thrive.

- The ability to be flexible problem-solvers and decision makers, including the ability to resolve conflict in creative, nonviolent ways and an appreciation of and inclination toward involvement with social justice.

- Communicative abilities, e.g., being able to participate in discussions and argue thoughtfully and the inclination to serve others and participate in acts of good will.

- Collaborative capacities, e.g., learning to compromise and work together toward a common goal.

21st Century Skills

Vooght and Roblin (2012) conducted a meta-analysis of 21st century skill frameworks and found that common components of these frameworks were communication, collaboration, information and communication technology (ICT) related competences, and social and/or cultural awareness. Also included on most lists are creativity, critical thinking, and problem solving, as well as generating relevant high quality products. Teachers must master these 21st century skills if they are expected to prepare their students for success in the knowledge economy. Participation in a knowledge economy requires new skills and an advanced level of autonomy and decision-making capability in order to adapt quickly to changing knowledge resulting from technological advances and rapid obsolescence (Powell & Snellman, 2004). These societal and economic factors challenge teacher preparation programs to recreate themselves and better prepare teachers to meet the needs of the 21st century (Wideen, 2013). Open learning environments are recognized as one representation of learning structures appropriate to the knowledge economy (Peters, 2010). Chris Dede (2010) delineated a categorization of 21st century tools and related skills based the comparison of several frameworks. The categories include: sharing (communal bookmarking, photo/video sharing, social networking, writers’ workshops/fanfiction), thinking (blogs, podcasts, online discussion forums), and co-creating (wikis/collaborative file creation, mashups/collective media creation, collaborative social change communities).

These tools enable users to participate in open and networked courses (Evans, 2015; Graham, 2015). Connectivism proposes a convincing framework for the open and networked course which relies explicitly “on the ubiquity of networked connections between people, digital artefacts, and content, which would have been inconceivable as forms of distance learning were the World Wide Web not available to mediate the process” (Anderson & Dron, 2010, n.p.).

The concept of Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) emerged from a consultancy project sponsored by the Canadian Government, which suggested that that there was a need to capitalize not only on the digital infrastructure but also on the combined human and digital networks, which emerge from it (McAuley, Stewart, Siemens, & Cormier, 2010). Consequently cMOOC (Connectivist Massive Open Online Course) proposed an instructional design structure that attempted to harness and build upon these networks. Learning in the collective (Thomas & Brown, 2011) presents a way of understanding the activity of students within an open and networked learning environment. Learning in the collective requires that students become active members of the network – both drawing from the network’s resources and adding to them. One is a member of the collective only to the extent that one contributes to and participates within the collective (Brown & Thomas, 2013). The activity of a collective diminishes the authoritative viewpoint of any individual member. Arguably, more than in any other learning configuration, the collective lends itself to a community of equals with common goals and interests, in which all members contribute equally.

Method

We base the analysis of this case study on Dewey’s (1916) ideas about democracy and education, the skills and dispositions for democratic participation set out by Cohen (2006), and a framework for 21st century skills (Vooght & Roblin, 2012). Yin (1984) defines case study as “empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context; when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident; and in which multiple sources of evidence are used” (p. 23). This research intends to examine, based on tweets, blog postings, and course products, the experience of students in the #seaccr group, how participation in the #seaccr network influenced students’ experiences, and why participants’ experiences differed in this context from the context of courses without a focus on the learning community. Analysis of data from students’ tweets and blogs will potentially lend support for our development of a theory of democratized on-line learning.

Participants

Our students are in-service and pre-service teachers as well as educational technology professionals. In total, 26 students participated in the course – 20 women and 6 men. All participants gave consent for the use of their data (blogs, tweets, email etc.). The eighteen students in the Classroom Research course consisted of six Elementary Master of Arts in Teaching (M.A.T.) students, two M.Ed. Reading students, seven M.Ed. Maths students, one Early Childhood Education student, and five M.Ed. Technology students. The eight students in the Impact of Technology on Student Learning course included two Career and Technical Educator professionals taking the course as an elective, and three M.Ed. Technology students. While participants in the Educational Technology course were seasoned in-service teachers or training professionals, many in the M.A.T. course only recently earned their teacher certification and completed this course during their first year of teaching. Most of these students had never before engaged in a formalized research process. In general, M.A.T. students are in a transitional space in which they evolve from teacher candidate to novice teacher. In our experience, being in this space creates a state of disequilibrium (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958) for M.A.T. students on both a professional and academic level. By contrast, most of the Educational Technology students have completed at least one action research project and are entering a more sophisticated level of research as district, university, or not for profit technology leaders.

Procedure

We had several goals as we designed the open online course. Because of the vast distances between our students and us, the need for authentic engagement was vital. According to Moore (1991) in distance learning, as physical distance increases, the need for intentional strategies to create intentional structure for instructional dialogue also increases: this is termed transactional distance. We wished to design a community that proliferated to the extent that transactional distance was reduced or eliminated through multiple paths to engagement and feedback. Further, we sought to encourage a more authentic conversation that could perhaps endure beyond the bounded course environment. We also wanted teachers to think like scholars, using data and research to make decisions, rather than relying only on experience and possibly spurious information.

As we had already experienced a siloed e-learning environment, we attempted to bridge the transactional distance by building a learning environment that would endure beyond the start and end dates of the course. We created a structure for a professional learning network that invited students to communicate, collaborate, think critically, and apply ICT skills, using popular social media tools. Rather than requesting to meet a “walled garden” requirement (e.g., “you have to respond to two discussion board posts,” or “go into this working room and talk about methods for 30 minutes”) (England, 2010), we attempted to make dependency on others and the need for peer support part of the course design. Students would be required to make choices about how, when, where and with whom they collaborated based on their learning needs and interests.

There were risks involved in this design. We knew the students would find themselves at the center of the learning space, responsible for their own learning and the learning of others. From experience, we were aware this would be disconcerting to many learners. Moreover, while the general process and expectations of the course were clearly delineated, individual students would choose the way they engaged in the process in terms of choosing resources and technology tools, and levels of interaction with their personal learning network (PLN). We realized this would put many students in a state of disequilibrium (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958) that could be uncomfortable and challenging for them. Finally, students would be required to develop and maintain a learning community on their own. We knew that technology would be an obstacle for some students, therefore we attempted to keep the design quite straightforward – mandating the use of blogs and of Twitter, but allowing all other tools in an optional manner.

Another equally important goal was for students to develop a foundational understanding of classroom research and the way that one creates, manages, and completes one cycle of action research to benefit their practice. We provided source documents and models to students to facilitate this understanding. In addition, we encouraged students to share their own writing with each other. Finally, through the blogs, students were required to locate supplementary resources and share with others to build the foundational understanding of the practice, intent, and outcomes inherent in action research.

We dubbed our open learning community #seaccr (Southeast Alaska Classroom Research). We created the learning space in the open in the hope that students would encounter a diversity of ideas and perspectives beyond those of the class enrolees. We hoped that all students would find entry points for connection with others because of the number of potential interactions that presented themselves. We hoped to continue our own development as facilitators and contributors in an online environment different from what either of us had experienced in the past.

We began the class with a synchronous WebEx video conference. During the first week of the class, we were careful to insure that students gained the basic skills necessary for success in their study. We scheduled a WebEx meeting during which we went over the syllabus and demonstrated how to use WordPress to set up a blog, and how to use Twitter to communicate synchronously. During the WordPress demonstration, many students set up their blogs, and learned how to make a posting. They made their first blog postings and asked questions. During the Twitter session, we demonstrated the use of Tweet Deck for organizing and following Twitter feeds, and shared some hints for reducing spam and for further organization. The group discussed the purpose of Twitter in the course, and practiced tweeting while the demonstration was going on. The mood of the group ranged from slight panic, to cautious optimism when the session ended. We invited students to tweet and practice prior to the scheduled Twitter session. We designated Week 1’s Twitter Topic “Play Week,” and invited students to a Twitter “play date” in which we asked students about our favourite television shows, favourite web sites, recipes, and hobbies. We also invited students to ask any questions they wished to have answered. As the course proceeded, we provided students with additional guided reflection questions, watched for misunderstandings, and encouraged interaction. Students engaged in the processes of classroom research. Starting in Week 3, we emphasized the importance of students answering questions asked by other students on Twitter, and we tried to move to the background a bit. Week Seven wrapped up the course. We held a focus group through WebEx and students shared their project presentations.

Data Sources

Data sources included student created blogs, student and faculty tweets, audio data from focus groups, archives of WebEx video conferences, and course related emails. We discussed our impressions and interpretations as researcher participants during the course, after the course ended, and during the analysis of participant data. These discussions formed the basis of reflexivity. Reflexivity is an awareness of the researchers’ contribution to the construction of meanings throughout the research process and an acknowledgment of the impossibility of remaining “outside of” one’s subject matter while conducting research (Patton, 2001).

The bulk of participant data came from student blogs and responses to the blogs of others. We harvested the blogs of all the students participating in the class, and comments made to those blogs for each of the seven weeks of blogs required for the course. We collected participant tweets from our twice-weekly Twitter sessions and organized them by participant and week. Groups of blog postings, tweets, and other input organized week by week became our primary documents for analysis.

At the end of the course, we invited students to participate in a focus group. We asked the following questions:

- What do you think collaboration looks like in a professional learning network?

- How easy was it to communicate with others as you engage in this course structure? Were your colleagues accessible? Were they responsive?

- Was this class easy or hard? Why or why not?

- What does it look like to fail or to succeed in this class?

We also invited students to ask any questions they wished to have answered. Some students choose to give unsolicited feedback to us about the course and their experience in emails and tweets. We use these quotes for their value as exemplar statements to support other data.

Analysis

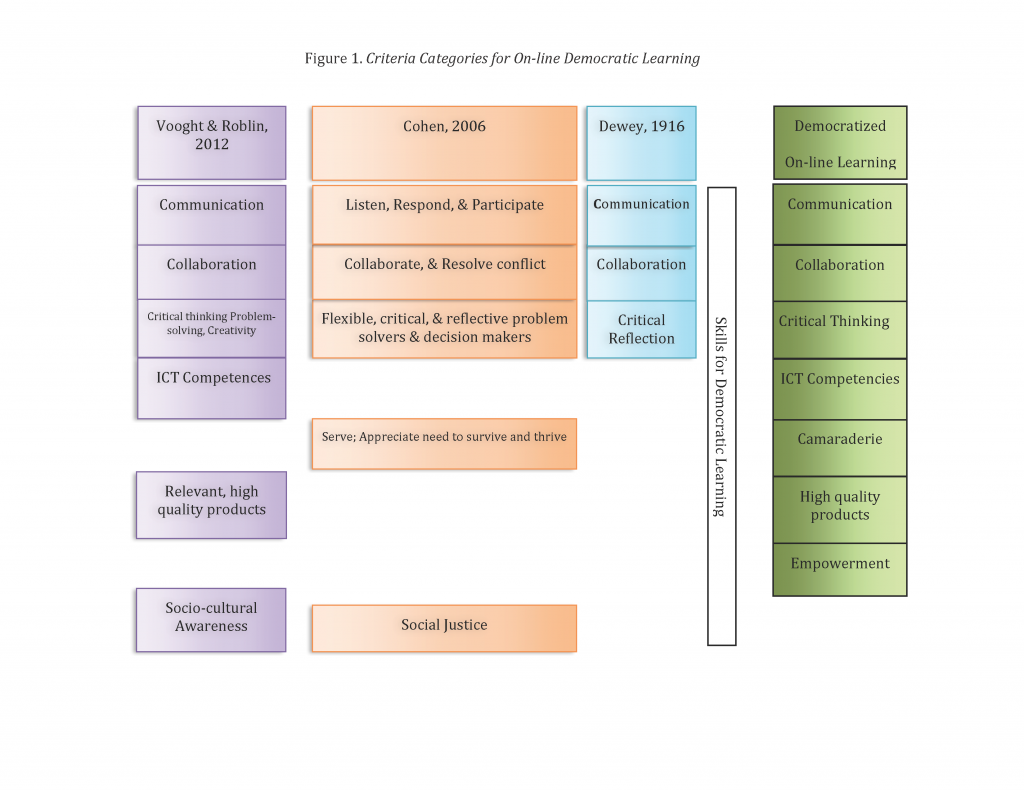

After an initial review of Dewey’s (1916), Cohen’s (2006), and Vooght and Roblin’s (2012) criteria, we grouped similar ideas from their criteria into categories that we used for content analysis coding. Figure 1 represents the skills for democratic learning derived from Dewey’s, Cohen’s , Vooght and Roblin’s criteria, and how their relate to our coding categories.

The codes we developed as criteria for content analysis of quotes are: communication, collaboration, critical thinking, ICT competencies, and camaraderie. More specifically we measured communication by the presence of appropriate, effective student interactions on Blogs and Twitter. ICT competencies were represented by students’ successful use of technology and tools.

Figure 1. Criteria categories for on-line democratic learning

We did not collect quotes for the code high quality products represented by students’ Classroom Research Projects. While we did not initially code for empowerment, when we discovered a large number of quotes that fit into this category, we re-ran the analysis including this code.

ATLAS.ti is a workbench of qualitative tools that provide a systematic approach to unstructured data that might not be appropriate for formal statistical approaches. It offers a variety of tools for accomplishing the tasks associated with any systematic approach to qualitative data. Using the qualitative data analysis tool ATLAS.ti we were able to code the data, view different possibilities for relationships among codes, and examine options for meaning making through several semantic lenses.

To prepare data for ATLAS.ti analysis, we developed codes based on criteria for democratic learning we would use to organize the tweet and blog quotes. Following an initial reading and using the concepts of collaboration, critical thinking, ICT competencies, camaraderie, and communication, we created broad categories for content analysis of project papers using ATLAS.ti (for the purposes of the ATLAS.ti analysis, these large categories are called ‘code-families’). Using the same concepts we then created ATLAS.ti ‘codes’ used for searching for specific words or ideas within the text of each project paper.

From a methodological standpoint, using ATLAS.ti codes serve a variety of purposes. Codes capture meaning in the data and are classification devices at different levels of abstraction that can applied to create sets of related information units for the purpose of comparison. Coding of text quotes in ATLAS.ti can occur in several ways. We first read tweets, blogs, and emails and then ‘free coded’ quotes by dragging the determined codes onto the documents. ATLAS.ti collects these codes for later analysis. As a check on our work, we also ran the ‘auto-coding’ tool. This tool looks for specific instances of words and synonyms for these words from the codes and code-families we determined. When the program finds an example of the code, the user must accept or reject the quote chosen by the ATLAS.ti program.

Codes

Collaboration

Quotes coded as collaboration are comprised of interactions that indicated students were working with each other to find an answer, solve a problem, complete a task, or meet a shared goal. According to Thomas and Brown (2011), a unique opportunity for networked learning occurs in the “collective,” an organic community to which we choose to belong in order to capitalize on, “people skills and talent that produces a result greater than the sum of its parts” (The Emergence of the Collective, para. 4). Participation in the collective is vital in order for belonging to be established. Those who wish to be a part of a collective are members only in proportion to their participation in the organic community. There are several ways one might establish belonging as a part of a collective. Blogs create a unique opportunity to begin to contribute and participate in the collective, and studies demonstrate that within classes blogging can lead to feelings of belonging and participation (Garcia et al., 2013; Reeves & Gomm, 2012). In addition, learning communities based in Twitter have been recognized as organic, naturally satisfying and authentic in terms of professional development potential (Ross, 2013). Educators noted that back channeling during Twitter could be highly effective for professional development (Toledo & Peters, 2013). Even younger students and their teachers report tweeting as effective for gaining answers to questions, and receiving academic support (Cohen & Duchan, 2012).

Critical Thinking

Ennis (1991) provides perhaps the best-known definition of critical thinking, “reasonable reflective thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do” (pp. 1–2).

We define critical thinking as disciplined thinking that is clear, rational, open-minded, and informed by evidence. In critical pedagogy the concept of critical thinking includes the ability to recognize and overcome social injustice (McLaren, 1994). Therefore, we include evidence of sociocultural/multicultural awareness or examples of a social justice perspective as critical thinking. We also include independent problem solving and examples of creativity in this code. tem Dam and Volman (2004) describe characteristics of instruction that facilitate critical thinking, the development of students’ epistemological beliefs, active learning, a problem-based curriculum, and purposeful interaction between students. Critical thinking quotes were a subset of the broader category of communication.

Camaraderie

Professional learning communities are not about building camaraderie for camaraderie’s sake. In this case, camaraderie evolved from collaboration on the processes and products of the course and enhanced the empowerment individuals reported. We see evidence of professional (educators), situational (the course) and intellectual (research focused) camaraderie. Participants in #seaccr worked as a PLN engaging in a cycle of questioning and product sharing that promoted the different facets of camaraderie. These interactions, conducted with a spirit of support, loyalty, and friendship, we believe, contributed to higher quality products. Quotes that demonstrated a spirit of support, loyalty, and friendship we coded as camaraderie.

Communication

Quotes coded as communication include one-way and two-way communications that directly relate to the processes or products required for the course that are appropriate, effective student interactions in blogs and on Twitter. Communication might include any of the other code sets.

Analysis and Results

Collaboration, Critical Thinking, Camaraderie

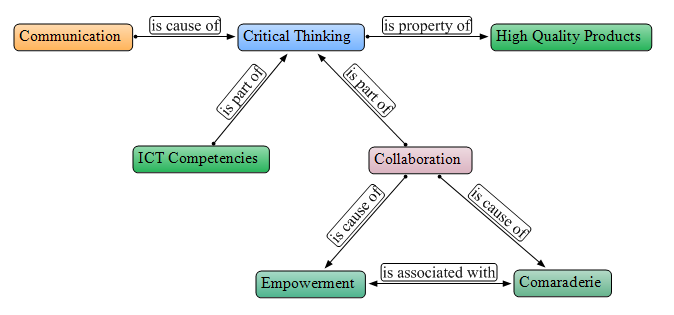

We collected student tweets and blogs, categorized these quotes conceptually, and created codes for analysis. The resulting analysis required an explanation for the appearance of Empowerment and what part this phenomenon played in the #seaccr experience. Ideas about empowerment were not present in other models and its prominence required an explanation. Figure 2 represents the #seaccr experience based on the analysis of codes in ATLAS.ti.

Figure 2. The #seaccr experience based on the analysis of codes in ATLAS.ti

At the center of the #seaccr experience is critical thinking. From the relationships revealed through the ATLAS.ti analysis, it is seen that communication has a direct effect on critical thinking. This makes sense because tweeting, blogging, responding to blogs, submitting work to a portfolio system, joining Web-Ex sessions, and designing and writing an APA style research project all required critical thinking by students. Also contributing to critical thinking are ICT competencies and collaboration. Collaboration is part of a larger, iterative process where collaboration is a cause of both camaraderie and empowerment, which are associated with each other. The power of this iterative process feeds back into critical thinking and together with ICT competencies and communication, contributes to the high quality products we see in this case. Table 1 shows the number of codes found across all seven weeks of participant blogging.

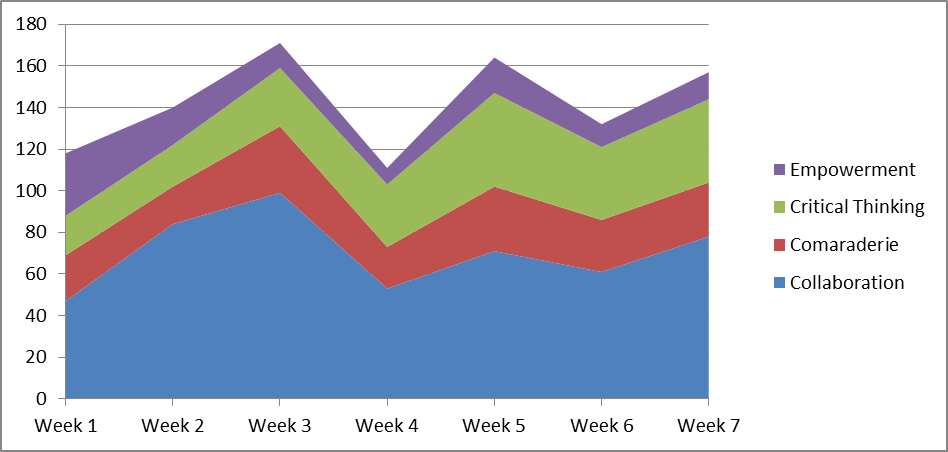

Table 1. Number of codes found across all seven weeks of participant blogging

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 7 | Totals: | |

| Collaboration | 47 | 84 | 99 | 53 | 71 | 61 | 78 | 493 |

| Camaraderie | 22 | 18 | 32 | 20 | 31 | 25 | 26 | 174 |

| Critical Thinking | 19 | 20 | 28 | 30 | 45 | 35 | 40 | 217 |

| Empowerment | 30 | 18 | 12 | 8 | 17 | 11 | 13 | 109 |

| Total | 118 | 140 | 171 | 111 | 164 | 132 | 157 | 993 |

Quotes coded collaboration occurred 493 times; quotes coded camaraderie occurred 174 times, critical thinking – 217 times, and quotes coded empowerment – 109 times. The chart below is a representation of the course experience based on the occurrences quotes for each code. Quotes for collaboration peak in Week 3 as students completed their literature reviews, then taper off as they engaged in data collection and analysis. Camaraderie ebbs and flows closely following empowerment. Critical thinking peaks in Week 5 as students presented their research proposals to the PLN for feedback. Quotes for empowerment peak in Week 1 and are likely because of ‘Play Week’ and students developing efficacy around Twitter, blogs, and LiveText.

Learning processes, which we capture as quotes and in codes, do not occur in isolation. When developing our model of democratized on-line learning, we also wanted to examine the co-occurrence of codes (Table 2) and quotes to better capture the integrated learning processes.

Table 2. Code co-occurrences

| Collaboration | Camaraderie | Communication | Critical Thinking | Empowerment | |

| Collaboration | 40 | 250 | 47 | 26 | |

| Camaraderie | 59 | 7 | 12 | ||

| Communication | 115 | 44 | |||

| Critical Thinking | 7 | ||||

| Empowerment |

Communication and collaboration are strongly associated, and this makes sense. The act of collaborating also requires the act of communication. Also strongly associated are communication and critical thinking. In the context on an on-line, networked course, this is essential and we were pleased to see it played out in the data. Next, in terms of strength of association are communication and camaraderie, and an association between critical thinking and collaboration. Then we see the interplay of collaboration and camaraderie and communication and empowerment. Finally, we see the association between collaboration and empowerment and critical Thinking and camaraderie. Figure 3 visualizes the ebb and flow of codes week to week and the association of codes to each other.

Figure 3. Code occurrences in student blogs by week

Once again, you see the learning processes working together and the strength of those interactions. This chart also presents a visual of how learning processes and the interactions of those processes changes over time and in relation to the focus of the course that week. It was striking to note the dip in all coded comments in Week 4. While expectations were the same from this week to all others, apparently some difference occurred. This was the week that students submitted annotated bibliographies to us, and we provided feedback. With the exception of the final project, this was the only project that was assessed solely by the instructors of the course. The significant dip in occurrence of all codes this week seems to indicate the way that students shifted from a student-centered environment back into a teacher-centered environment. Then, in Week 5, activity resumed and increased as students reviewed each other’s proposals and provided feedback.

To provide some depth of understanding of the meaning behind our codes, we present some exemplar quotes for codes Collaboration, Critical Thinking, and Camaraderie in Table 3.

Table 3. Quotes exemplifying codes

| Collaboration | |

| “Thank you for the time to review my paper.I love the feedback.” | “In the end, when the paper is complete it will represent more than just a completed action research paper it will also represent the importance of collaboration.” |

| “Within the process, we collect data and think about what patterns emerge. We confer with those in our PLN to see if our thinking makes sense.” | “Most importantly, I gained a partner to help me with this project. She was as excited as I am… and has sights on making this project useful enough to warrant presenting at ASTE this winter!” |

| Critical Thinking | |

| “After reading everybody’s comments I realized I had some tweaking to do on my question. (name redacted) pointed out that my verbage of ‘dig deeper’ was too vague and open-ended and that it needed something a little more Bloom’s-esque.” | “What I have begun thinking about is the amount of literacy I am actually using in classroom, and my answer is, “Not enough.” I need to be reading and writing more frequently with my students than I currently am.” |

| “I am thinking, how do we maintain excellence as we innovate?” | “My thoughts have changed a lot since I took the time to read and try to understand the literacy standards.” |

| Camaraderie | |

| “It was really nice to introduce ourselves and find out just how far apart, yet close together we all are.” | “Sometimes just having another person say, ‘yeah, that sounds like a great idea! run with it!’ is all we need.” |

| “We are all educators in some way and connected by our willingness to teach our students.” | “I felt quite a bit of camaraderie from my peers as we fumble at the beginning of this class together.” |

ICT Competencies

While some students had learned to use a wide variety of ICT tools prior to #seaccr, as they developed PLNs outside of the program, only a few of the class participants had used these tools for graduate level coursework. Other students, depending on when they had taken their foundational courses and in which program they studied, had not learned to tweet, blog or make a screencast prior to their #seaccr experience. They learned these skills for the first time in the context of classroom research.

Students gained new ICT competencies such as the ability to manage multiple logins and communication paths. They learned to manage their online identities, to curate information for use by others, and to influence the learning of others through their PLN strategically. Finally, students demonstrated dispositions related to collegiality and support for their expanding network, and social awareness of their responsibility to assist their colleagues as they navigated the learning experience. Comments from students illustrate their learning: “I think the Twitter sessions are good, I do find it a fun way to communicate, collaborate and learn.” and “After six weeks of Tweeting and blogging, I’m converted.” Many students reported that Twitter sessions, while offered as optional, were essential for their learning exemplified by these comments: “I must repeat what I wrote last week! I know the Twitter sessions say, ‘Optional’ but they are the bulk of my learning in this class.” and “Interesting to hear about the Twitter sessions – I agree as well they’re where a lot of new learning happens for me and also the interaction gives me a lot of impetus to ‘do more’. These responses further support the necessity for development of ICT competencies as part of the experience and the importance of these competencies for empowerment, the development of content knowledge, and ultimately the necessity of this element in the democratic on-line learning model. We also noted that competitiveness arose as students gave feedback to others. Much of this occurred because of participation in the Twitter sessions. Some students set high expectations for themselves, and these expectations became public; other students then challenged themselves to meet or exceed their colleagues’ performance. We also noted that as students blogged their work and thoughts in this very public way, some students did more self-assessment and reflection, and demonstrated more motivation than was evidenced in postings for the relatively more closed environment of the discussion board.

High Quality Products

A high quality product in this case was a classroom research project that met the criteria for the ‘Exceeds’ elements, as detailed in the rubric provided to students: “The final paper is complete and is in APA format. The paper is relevant and insightful. The research supports the improvement of professional teaching practice and can be applied to other teaching and learning situations”.

Student products focused on improving their professional practice and enhancing learning among their students. Projects included topics such as how to integrate technology as a differentiation tool; implementing the new core literacy standards with Alaska Native students; classroom environments for English-language Learner (ELL) students; and multi-level math instruction in multi-grade classrooms. These products demonstrated that students examined and analyzed problems with a critical eye, then addressed them in relevant and creative ways. Moreover, student products were of a high quality: much higher than in previous sections of the course that we presented through our university’s content management system. We believe student performance was enhanced because students had to make an intentional effort to engage with the PLN: there was no lecture and no text to rely on. Importantly, the professional learning network in this case was authentic. Students made choices about how, when, where and with whom they collaborated based on their learning needs and interests.

Empowerment

As we reviewed quotes, created codes, and re-read quotes for coding, we discovered a particular set of quotes that did not quite fit into our established categories. These quotes made special reference to a new skill the individual had learned, new knowledge they had gained, or an idea that they could apply their new skills and learning. These quotes also demonstrate the individual is in the process of increasing their efficacy and capacity to make choices and take positive action.

A student shared, “Pretty exciting to enter the new world. Interacting with a host of teachers and educators, my new PLN (rather than a PLC [professional learning community]) is proving to be eye opening. I am excited to learn from and to share my knowledge with my PLN.” Others added, “I have learned to be open to learn something new.” “This class pushed me to learn new things!” and “Steep learning curve, but still climbing!” Also, “I found the entire process so enlightening but the end result was even more eye opening. To see it all written out and direct quotes to back it up. Wow, very cool class Anne!”

We also received feedback about feelings of empowerment beyond the parameters of the course, “I’m also not as afraid of the social media tech as I once was, and though my students may not use it now they will in the future” and “I am feeling more confident in my ability to differentiate instruction.”

The data analysis also revealed a high number of shared quotes between camaraderie and empowerment. We call this intersection of codes between camaraderie and empowerment, ‘cheer-leading’. In an attempt to understand this relationship, and how it manifested among participants, we selected quotes from the Twitter sessions that we coded as both camaraderie and empowerment. Examples of these are:

- “Feeling very passionate about being a teacher tonight. Thanks everyone for a great discussion.”

- “Friends working together get things done!”

- “When you need some motivation check out: http ://( redacted).”

- “It seems like our projects are off to a great start!”

- “That’s awesome! Way to think outside the box.”

- “I would just like to say I am really looking forward to some of the projects, as they will be wonderful!”

Discussion and Conclusion

We accept the premise that teachers must master 21st century skills (Vooght & Roblin, 2012) if they are expected in turn to prepare their students for success in a global knowledge economy. Educators who completed the #seaccr experience have improved ICT skills, developed a PLN, and improved their general knowledge about teaching and learning through the classroom research process. We often think of community building and its result, collaboration, as separate or parallel to academic learning. In this case, they two were interwoven. Open learning environments like #seaccr, are recognized as one representation of learning structures appropriate to the global knowledge economy (Peters, 2010). These societal and economic factors challenge teacher preparation programs to recreate themselves and better prepare teachers to meet the needs of the 21st century students (Wideen, 2013). However, these 21st century skills may not be enough.

Glaser (1985) notes that U.S. students lack higher-order thinking abilities even though a democratic society requires people to think critically and Cohen (2006) argues the goals of education need to balance academic learning with the competencies necessary for democratic participation and good quality of life.

In today’s classroom, political and economic forces often drive teaching and learning. Generally, teachers are not taught to recognize or combat these forces. The current climate of inflexible curricula and evaluations for students and teachers sometimes forces teachers to neglect the types of school experiences that support the development of democratic perspectives in their students. This will likely contradict teacher philosophies about education; however, teachers may feel they have no choice but to comply.

Participation in a global knowledge economy requires new competencies, a high level of autonomy and decision-making skill, and the ability to adapt to changing rapidly changing knowledge and technological advances (Powell & Snellman, 2004). Further, a democratic experience with learning in schools (community, collaboration, and critical reflection) provides the experiences needed for later effective participation in a democratic society (Dewey, 1916). Dewey (1916) would argue that to accomplish these goals, students ought to have same power and responsibility for their learning as their educators. Educators are responsible, then, for providing students with relevant learning opportunities that ultimately enable students to contribute to a democratic society.

Teachers in #seaccr became the providers, as well as consumers, of knowledge: sharing learning and expertise, and blurring the roles of teacher and learner and as a result, democratized the learning experience. In a generalized way, comments provided by the participants suggest that when teachers learn in democratized environments they are better prepared to create and facilitate democratized learning environments in their classrooms, helping their students to gain the knowledge and skills to participate in a democracy.

In the 1980s, on the assumption that this increased decision-making power would improve instruction and learning, teachers were given the authority to make decisions in the classroom (Lichtenstein, et al., 1991). Similar efforts occurred during the same time, to imbue students with self-esteem, rather than provide them opportunities to develop self-efficacy. These attempts at “empowering” were mostly ineffective (Lichtenstein, et al., 1991). Real empowerment must come from the individual and must have a strong foundation in knowledge of their broader professional community, knowledge of education policy, and knowledge of their subject area (Lichtenstein, et al., 1991). The #seaccr experience provided the opportunity for participants to increase knowledge in all these areas. Further, by including students in decisions about learning, inquiry, and action, participants in #seaccr co-constructed and identified with the means and messages of the classroom, leading to a feeling of empowerment (Cammarota & Fine, 2008).

As we reflected on previous research about democratic learning, we realized that empowerment was a missing element. Our research indicates, however, that it is a very important aspect of democratization. Our framework for democratic learning (Figure 2) includes Empowerment as important element in creating learning spaces where democratic learning can occur. It is apparent that 21st century skills and the ability to use, gain, and apply knowledge are essential in today’s world. However, if a teacher is not empowered to use these skills and knowledge to effect change in their classrooms, 21st century skills remain unused.

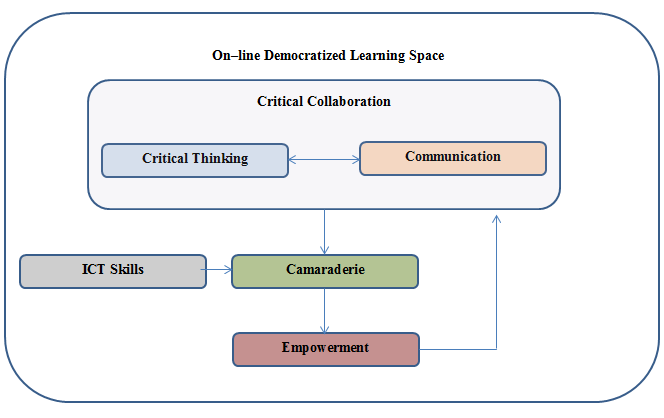

The resulting theory of on-line democratized learning (Figure 4) explains not only the interactions between and among critical thinking, ICT competencies, collaboration, and camaraderie, but also includes the concept of empowerment, as a space from which the capacity to engage in democratic action emerges. Critical thinking, as we know, cannot occur or be sustained in isolation, it must be shared, evaluated, reflected upon, and re-shared, and this requires communication. Communication, in our model, must include critical interactions that generate and foster collaboration resulting in an iterative process. The crux of our theory is this nexus of critical thinking and collaboration that results in what we call critical collaboration. This critical collaboration amongst peers results in a strong camaraderie that empowers the members of the group. The outcome camaraderie, with the addition of ICT skills, produced behaviours in students we describe as empowerment. It is this individual empowerment, absent from other models, demonstrated through the sharing of critical ideas, that creates an on-line democratic learning space where all voices are heard and consensus can be reached.

Figure 4. A theory of on-line democratized learning

This democratized learning space is the kind of space where Dewey (1916) believes students ought to have same power and responsibility for their learning as their educators that ultimately enables students to contribute effectively to a democratic society. It stands to reason that when a teacher becomes individually empowered around their practice they are likely to participate more directly in school-based decision further democratizing these institutions as well. Empowerment of an individual or group can result in a change in the distribution of power. Power structures in schools and other educational institutions were not an explicit focus for us as facilitators or for the students in the course. However, in the context of teaching, change in power structure has implications for children, classrooms, schools, and the broader institution of education.

Finally how important ICT skills are to this model cannot be determined. We wonder if a similar space for democratic learning through empowerment would occur without the learning and practice of ICT skills, in a face-to face or a course with a blended format for example.

References

Anderson, T., & Dron, J. (2010). Three generations of distance education pedagogy. TheInternational Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(3), 80-97. Retrieved from: http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/890/1663/ on March 22, 2015.

Brown, J. S., & Thomas, D. (2013). Learning in the Collective. Hybrid Pedagogy. Retrieved from: http://www.hybridpedagogy.com/journal/learning-in-the-collective/ on March 22, 2015.

Cammarota, J., & Fine, M. (2008). Revolutionizing Education: Youth Participatory Action Research in Motion. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cohen, A., & Duchan, G. (2012). The usage characteristics of Twitter in the learning process. Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects, 8(1), 149-163.

Cohen, J. (2006). Social, emotional, ethical, and academic education: Creating a climate for learning, participation in democracy, and well-being. Harvard Educational Review, 76 (2), 201-237.

ten Dam, G., & Volman, M. (2004). Critical thinking as a citizenship competence: Teaching strategies. Learning and Instruction, 14, 359-379.

Dede, C. (2010). Comparing frameworks for 21st century skills. 21st century skills: Rethinking how students learn, 20, 51-76.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education. New York: The Free Press.

England, A. (2010). Open content: From walled gardens to collaborative learning. Incite, 31 (1/2), 10.

Ennis, C. (1991). Discrete thinking skills in two teachers’ physical education classes. The Elementary Journal, 91, 473–486.

Evans, P. P. (2015). Open online spaces of professional learning: Context, personalisation and facilitation. Techtrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 59(1), 31-36.

Garcia, E., Brown, M., & Elbeltagi, I. (2013). Learning within a connectivist educational collective blog model: A case study of UK higher education. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 11(3).

Glaser, E. M. (1985). Critical thinking: educating for responsible citizenship in a democracy. National Forum, 65, 24–27.

Graham, L. & Fredenberg, V. (2015). Impact of an Open Online Course on the Connectivist Behaviors of Alaska Teachers. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. Retrieved from: http://ascilite.org.au/ajet/submission/index.php/AJET/article/view/1476/1254

Inhelder, B. & Piaget, J. (1958). The growth of logical thinking: From childhood to adolescence. (A. Parsons & S. Milgram, Trans.) New York: Basic Books.

Lichtenstein, G., McLaughlin, M., & Knudsen, J. (1991). Teacher empowerment and professional knowledge. Consortium for Policy Research in Education, CPRE Research Report Series RR-020.

McAuley A., Stewart B., Siemens, G., & Cormier, D. (2010). The MOOC model for digitalpractice. Retrieved from: https://oerknowledgecloud.org/sites/oerknowledgecloud.org/files/MOOC_Final_0.pdf on July 1, 2013.

McLaren, P. (1994). Foreword: critical thinking as a political project. In S. Walters (Ed.), Re-thinking reason: New perspectives in critical thinking (pp. 9–15). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Moore, M. G. (1993). 2 Theory of transactional distance. Theoretical principles of distance education, 22

Patton, M.Q. (2001) Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Peters, M. (2010). Three forms of the knowledge economy: Learning, creativity and openness. British Journal of Educational Studies, 58 (1), 67-88.

Powell, W. W., & Snellman, K. (2004). The knowledge economy. Annual Review of Sociology, 199-220.

Reeves, T., & Gomm, P. (2012). Blogging all over the world: Can blogs enhance student engagement by creating a community of practice around a course? Cutting-edge Technologies in Higher Education, 6, 47-72.

Ross, C. R. (2013). The use of Twitter in the creation of Educational Professional Learning Opportunities. (Doctoral dissertation). Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, Texas.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: Learning as network-creation. Retrieved from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/networks.htm on January 27, 2014.

Siemens, G. (2004). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. Retrieved from http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm on January 27, 2014.

Thomas, D. & Brown, J. S. (2011). A new culture of learning: Cultivating the imagination for a world of constant change. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Toledo, C., & Peters, S. (2013). Educators’ perceptions of uses, constraints, and successful practices of back channeling. in education, 16(1).

Vooght, J., & Roblin, N.P. (2012). A comparative analysis of international frameworks for 21st century competencies: Implications for national curriculum policies. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 44 (3), 299-321.

Wilbur, G., & Scott, R. (2013). Inside out, Outside in: Power and culture in a learning community. Multicultural Perspectives, 15(3), 158-164.

Wideen, M. F. (Ed.). (2013). Changing Times in Teacher Education: Restructuring Or Reconceptualising? New York: Routledge.

Yin, R.K. (2003). Case Study Research: Design and Methods (3rd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

This academic article was accepted for publication in the International HETL Review (IHR) after a double-blind peer review involving three independent members of the IHR Board of Reviewers and two revision cycles. Accepting editor: Krassie Petrova (Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand), Editor-in-Chief Emerita, International HETL Review.

Suggested citation:

Jones, A. & Graham, L. (2015). Democratizing higher education learning: A case study of networked classroom research. International HETL Review, Volume 5, Article 6, URL: https://www.hetl.org/democratizing-higher-education-learning-a-case-study-of-networked-classroom-research

Copyright [2015] Anne Jones & Lee Graham

The author(s) assert their right to be named as the sole author(s) of this article and to be granted copyright privileges related to the article without infringing on any third party’s rights including copyright. The author(s) assign to HETL Portal and to educational non-profit institutions a non-exclusive license to use this article for personal use and in courses of instruction provided that the article is used in full and this copyright statement is reproduced. The author(s) also grant a non-exclusive license to HETL Portal to publish this article in full on the World Wide Web (prime sites and mirrors) and in electronic and/or printed form within the HETL Review. Any other usage is prohibited without the express permission of the author(s).

Disclaimer

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and as such do not necessarily represent the position(s) of other professionals or any institution. By publishing this article, the author(s) affirms that any original research involving human participants conducted by the author(s) and described in the article was carried out in accordance with all relevant and appropriate ethical guidelines, policies and regulations concerning human research subjects and that where applicable a formal ethical approval was obtained.