HETL Note: This article describes a mobile WeChat project that was initiated to test the effectiveness of English as a Foreign Language learning through a network-based mobile phone application. Based on quantitative and qualitative data, the project showed significant increases in student’s motivation and attitudes to learn. The project created a learning environment where students could better connect their classroom learning with practical life experience, which is especially helpful for students since learning a foreign language is a challenge and it benefits students to learn in a more authentic English learning environment.

Author’s Bio: Wuyungaowa has been a lecturer for 12 years at School of Foreign Languages, Inner Mongolia Normal University, China. She took her M. Ed. Studies in Curriculum and Teaching at Teachers College Columbia University, U.S. in 2008. She is sensitive to curriculum design, new technology, student-centered strategies and cross-cultural communication and is keen to the cultural exchange. She has been to Thailand, U.S., Australia, Sweden and India in different programs, conferences and seminars. Her expertise encourages her to think and act in a more thoughtful and creative way. Now she is working with colleagues on a manual for EFL (English as a Foreign Language) teachers and teacher educator to integrate Child Rights Convention into the actual teaching process. She may be contacted at [email protected].

Author’s Bio: Wuyungaowa has been a lecturer for 12 years at School of Foreign Languages, Inner Mongolia Normal University, China. She took her M. Ed. Studies in Curriculum and Teaching at Teachers College Columbia University, U.S. in 2008. She is sensitive to curriculum design, new technology, student-centered strategies and cross-cultural communication and is keen to the cultural exchange. She has been to Thailand, U.S., Australia, Sweden and India in different programs, conferences and seminars. Her expertise encourages her to think and act in a more thoughtful and creative way. Now she is working with colleagues on a manual for EFL (English as a Foreign Language) teachers and teacher educator to integrate Child Rights Convention into the actual teaching process. She may be contacted at [email protected].

Engaging EFL Learners through WeChat:

A Mobile Phone-Based EFL Learning Project in China

Wuyungaowa

Inner Mongolia Normal University, China

Abstract

A thirty-eight-day mobile WeChat project was initiated aiming at testing the effectiveness and potential of EFL learning through network-based mobile phone. The researcher collected both quantitative and qualitative data. Significant results were found in student’s motivation and attitudes, participation in WeChat tasks, skills, and their perception of others. Both students and the teacher met intended or unintended student-, teacher- and technology-related obstacles. Surprisingly, the project created a more flexible by-product which is still in use now by the previous project students.

Keywords: CALL, mobile phone, EFL, learning environment, WeChat, participation

Introduction

The Information Age provides a wealth of opportunities for people to communicate with each other by taking advantage of information technology, especially effective online communicative tools regardless of distance and time. In the field of language teaching and learning, history has witnessed the gradual emergence of computer-assisted language learning (CALL) and the progress of network-based language teaching (NBLT) (Beatty, 2003; Chapelle, 2001; Chapelle & Jamieson, 1986; Egbert, 2005; Nunan, 2006; Warschauer, 1996). Many researchers have studied various facets of CALL, through which we can learn numerous computer-assisted or network-based programs that were employed with multiple goals from historical, theoretical, pedagogical, practical or empirical perspectives (see Barson, Frommer & Schwartz, 1993; Brown, 2007; Chapelle, 2005; Egbert, 2005; Kern, 2006; Munca, 2008; Rahimi, Fatemeh Hosserini K., 2011; Richardson, 2006; Warschauer, 1996; Warschauer & Kern, 2000). The researches mirrored the course of CALL and threw light on an even more advanced technology-based EFL teaching and learning era.

The opportunities provided by information technology enable students to learn EFL by regular practice with their peers online in or beyond their classrooms (Chapelle, 2013; Egbert, 2005; Nunan, 2006). This practice covers a wide range of online activities such as collaborative projects, e-mail, blogs, web-based bulletin board communication, videoconferencing, podcasting, speech, multimedia presentations, etc. (Beatty, 2013; Brown, 2007; De Szendeffy, 2005). As Warschauer (2006) pointed out, in these activities, learner’s “interaction; reading and writing; and affect” have been three main topic areas that researchers have focused on (p. 208), which showed potential for success in using the CALL approach. Brown (2007) also identified a number of possible benefits from many researches when technology is involved in language instruction. The possible advantages can be learners paying attention to the language forms, multimedia experiences, individual responses, adjustment to learner’s own speed of communicating, a secure environment for making mistakes, responsiveness to teacher and classmates, opportunities to work collaboratively and regularly, exploration in the larger linguistic corpus and practicing the real-life skills in communicative and technology (Beatty, 2013; Brown, 2007). However, CALL needs to adhere to certain principles; otherwise it will bring challenges and problems to all the stakeholders in terms of participation, linguistic skills, communication, students and facilitators, technology itself, etc. (Beatty, 2013; Brown, 2007; Chapelle, 2006).

Learning Environment and Motivation

Teaching English as a Foreign Language (EFL) can be inefficient and ineffective if students lack interest and motivation (Dörnyei, 1994; Dörnyei, Csizér, & Németh, 2006; Gardner, 1985; Nunan, 2006; Oxford, 1996). Many researchers have proposed that the students learn by experiencing (Dewey, 1997; Tyler, 1986). According to Larsen-Freeman (2000), “when learners perceive the relevance of their language use, they are motivated to learn” (p. 140). Thus, building language by regular use of it through one’s life experience can be an option, which will shift the language form to language use in a more meaningful context, in which the learner’s motivation may be increased (Dörnyei & Schmidt, 2001; Schmidt, Boraie, & Kassabgy, 1996; Shoaib & Dörnyei, 2005; Warschauer, 2006).

As one of the key carriers of the technology, mobile phone nowadays is not merely a communicative tool for phone calls, messages and saving contact information. A mobile phone in 21 century may have more potentials on campus than a computer, which shows the importance of the mobile phone as a functional mini-computer in student’s school life. Under the CALL stream of research, mobile phone-based empirical studies have a relatively short history. However, as Beatty indicated (2013), the development of mobile phone technology has led to the hope of integrating mobile phone applications into EFL teaching and learning.

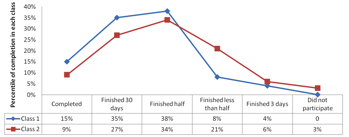

In China, English learning achievements in each university are differentiated by historical, geographical, economical factors combined with the quality of the enrolled students, their learning environment, motivation, resources, teacher’s qualifications, and other possible factors (Jia, 2007; Wen, 2012). According to Spolsky’s theory of conditions for language acquisition (2004), learners’ future language knowledge and skills will be affected by their present knowledge, abilities, motivation and opportunity to be exposed in the target language environment (see Figure 1). That is to say, in an ideal language learning environment, learners are supposed to use what they learn regularly to internalize the knowledge and transform it into practice (Chapelle, 2008).

Figure 1. Spolsky’s (2004) theory of conditions for language acquisition.

(Adapted from Egbert, Hanson-Smith & Chao, 2007, p. 2)

In order to acquire more meaningful knowledge and skills in the future by making use of the learners’ present knowledge and their physiological, intellectual and cognitive skills (Beatty, 2003; Egbert, 2005), the following project puts more emphasis on an English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learning environment where the learners can expose themselves more to the English language to increase their motivation, interest and make their behavioral adjustment in the process (Brown, 2007; Gardner, 1985). Based on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow, 1970), the researcher intends to reduce the learner’s needs for security, protection and freedom from fear in the learning environment, and focus on higher level needs such as sense of belonging and affection for the learning environment, through which the students’ motivation can be increased. Then an even higher tier of esteem will be pursued such as individual strength and status in the learning environment (Maslow, 1970).

The differences between ESL and EFL enhance the possibilities of the mobile phone project as such to create a learning environment or a working space for the students to constantly link their classroom learning with their daily life experience in a secure environment (Oxford, 1996). According to Oxford (1996), EFL (English as a foreign language) refers to the context where English is not frequently used in the learner’s daily life but only used for certain purposes such as English classes, English-Only companies, or occasions related to going abroad and the like. It is a challenge for the EFL learners to have an authentic English learning environment. Therefore, it is necessary for them to have a private space to apply what they have been learning to their real life experience.

Mobile Phone Learning Experience and WeChat

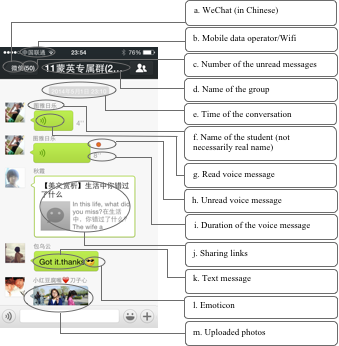

WeChat in China, in some ways a combination of Facebook, Twitter, Skype, WhatsApp, Blogger, etc., is one of the most popular mobile communicative tools with the functions of instant messages, voice box, audio chatting, video chatting, sharing local files or web links, etc. With integrative functions of a number of popular communicative tools or applications, a network-based mobile phone presents itself as an advanced platform for educators to introduce “constructivist learning environments” into the teaching process (Munca, 2008, p. 37). As Warschauer and Kern (2000) noted, network-based language teaching (NBLT) brings about a new series of possibilities in CALL which puts more emphasis on communication among EFL learners. Meanwhile, network-based mobile phones, similar to computers, will provide opportunities for the language learners to make use of the corpora (Chapelle, 2008) and “produce comprehensible output” (p. 37) because of mobile phone’s familiarity to the students and its immense frequency of usage.

Figure 2. Process and experience through WeChat.

Since WeChat is one of the most popular online communicative platforms in China, a thirty-eight-day WeChat project was initiated aiming at testing the effectiveness and potential of EFL learning through network-based mobile phone. Taking advantage of the multifunctional tools of WeChat, the research explores the possibility of a mobile phone learning environment for EFL teaching and learning in two university EFL classes in China. The WeChat project was designed to set up organized online activities for the students to communicate with each other in English on a daily basis, which can raise the students’ awareness of participation in the process of communication so that they can apply both their linguistic and communicative skills with other skills (Beatty, 2003, 2013; Chapelle, 2005). In this working space, the learners are also supposed to be able to interact and collaborate with the supportive functions of the application, which can arouse the learner’s awareness of more autonomous learning, creative expressions, decision making and more critical thinking (Munca, 2008).

Methods

Since each EFL undergraduate in this project had a mobile phone with one of the mobile data operators in China, it made the project possible to proceed. A chatting group was set up through the WeChat application on the mobile phone for the purpose of communication in English on a daily basis. Two second-year university EFL classes were involved, which were equipped with a number of WeChat group chatting rules, including what and how the students were going to talk each day, what the “taboos” in the group were, what information should be shared, how the teacher will evaluate through the group chat, etc. The researcher gave out questionnaires to all the students at the end of the project to understand more about students’ daily learning behaviors and motivation in this internet-based mobile project.

Both quantitative and qualitative data was collected, together with the teachers’ observations throughout the whole process, including the numbers of students involved each day, the number of entries, content area of chatting and web links that the students shared, and experience relevance, etc. At the end of the project, a survey and informal interviews were also conducted to evaluate the WeChat tasks. Thirty-four questions in the questionnaire have been studied for different purposes. The researcher compared the data of the two classes in order to learn more about the factors that affect students’ participation and effectiveness in the process.

As shown in Table 1, the project lasted for thirty-eight days from May 1, 2014 to June 7, 2014, when the EFL teacher was away for a training program out of the country. The WeChat group activity was assigned to two sophomore classes that the teacher taught that semester. One was Communicative English class with 26 Mongolian students learning English as a third language (Class 1) and the other was Business English II with 33 students learning English for business purposes (Class 2). The English proficiency of most of the 59 students can be regarded as intermediate or lower level. More than half of the students speak English as their third language and Chinese as their second language. Based on the knowledge of the student’s language level and for the purpose of the study, the researcher worked out a set of project rules covering the following five aspects:

- The students need to set up a WeChat group first or use the existing WeChat group that they already have for their class for the purpose of the WeChat project.

- In the WeChat chatting group, the students are supposed to send daily text messages including at least (altogether covering) ten non-repetitive notional English words—non-repetitive words in one’s own message as well as other students’ messages.

- In the WeChat group, the students are supposed to send daily audio messages including at least (altogether covering) ten non-repetitive notional English words—non-repetitive words in one’s own message as well as other students’ messages.

- In the WeChat group, the students are supposed to share a weekly link relevant to English study.

- In the WeChat group, English is the only acceptable communicative language except the links that the students will share.

Table 1

WeChat Groups

| Classes (Sophomores) |

Communicative English (Class 1) |

Business English (Class 2) |

| Number of students | 26 | 33 |

| Level | sophomore | sophomore |

| Duration of the task | 2014/5/1-2014/6/7 | 2014/5/1-2014/6/7 |

| Length of the project | 38 days | 38 days |

The two WeChat groups were set up by the students themselves. Class 1 initiated the group activities almost two weeks before the official beginning of the tasks. Class 2 began it a week before the project. Both groups communicated with each other in WeChat groups in Chinese and English in written form and adding Mongolian language in spoken form. After a reminder from the teacher on the project rules, English became the only communicative language in each group once it officially started.

Findings

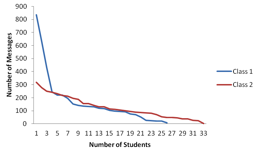

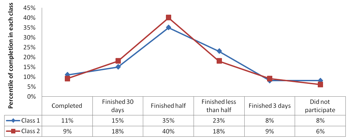

A total number of 59 students were involved in the WeChat project with more than 8000 messages in different forms such as text messages, voice messages, links, emoticons and uploaded pictures. The main topics of the conversations mostly focused on the students’ daily activities including their school-related life, schedules, events, homework assignments, stories, weather, travelling, shopping, thoughts of life, and people such as classmates, teachers, relatives, celebrities, etc. All the students have participated in the project, but performed very differently. Among the 59 students from two classes, only a few students sent above two or three-hundred messages during the 38-day project. According to the collected individual messages and answers to the questionnaires, participation varied depending on students’ time, energy, personality and some other factors. It echoes the previous studies on computer-mediated communication, where more balanced participation can be found than face-to-face communication, with “less dominance by outspoken individuals” (Warschauer, 2006, p. 209). Comparing the participation between the two classes as shown in Figure 3, it seems that Class 1 had very conspicuously active students as well as some non-active students.

Figure 3. Numerical Data of Class 1 and Class 2.

Motivation & Attitudes

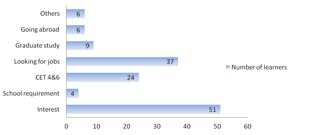

In order to understand more about the students’ motivation, attitudes and behavior in the EFL learning, the research included some questions with this focus in the WeChat project questionnaire. According to the data, more than 90% of the EFL learners were interested or very interested in English learning. 51 out 59 learners were learning English because of their interests (see Figure 4). 73% of the learners considered the instructor’s teaching methods the most important factor affecting their interests in EFL learning. Learning environment and usefulness of the language were their next concern. Relatively fewer learners thought that their future job would be related to English and that the teaching materials that the teacher prepared would affect their interest in learning. Only one fourth of the students felt interested in English because they paid more attention to the test scores.

Figure 4. Motivations of EFL learning.

Data mentioned above indicates the reason why the students learned English, which can direct the instructor how to instruct in his or her class (see Figure 4). At the same time, half of the learners also explained that they learned English because they wanted to pass the national College English Tests (Band 4 or 6) and more than half of them hoped to find jobs with the help of English proficiency. Fewer students showed that they wanted to learn English to go to further education, to go abroad or to meet the requirement of the school. When asked about not doing well in learning, a good number of them took responsibility themselves such as not putting enough effort or not being interested instead of blaming the external learning factors.

Participation in WeChat Tasks

WeChat project was the first time for the students to communicate online in English. Compared with voice messages that the students were required to send, sending text messages and sharing links in WeChat group were not hard to most of them. Strangely, these tasks were not completed as they should have been operated.

According to student feedback, only 4% of the students considered sending text messages for 38 days not easy; 54% of the students took the task as very easy. However, only 12% of the students completed the text message task (see Table 2); 76% finished 19 to 30 days, which is half or more than half of the task; 15% finished less than half and 5% of the students finished only 3 days. There are still 2% of them who didn’t participate in the task at all.

Table 2

Completion of text message task

| Completed | Finished 30 days | Finished half | Finished less than half | Finished 3 days | Did not participate | |

| Number of students | 7 | 18 | 21 | 9 | 3 | 1 |

| Percentage | 12% | 30% | 36% | 15% | 5% | 2% |

The students elaborated on their obstacles to the accomplishment of the task. Firstly, as for the text message requirement, the students were supposed to send daily text messages at least covering ten non-repetitive notional English words—non-repetitive words in one’s own message as well as other students’ messages. Students expressed their difficulties in finding words that did not appear in other students’ conversations if they began to talk later than the others. When they tried to check the dictionary and attempted to respond, the topic had been moved to another direction already. As indicated in their feedback, limited vocabulary and lack of expressions were two of the problems hindering the accomplishment of the tasks.

Secondly, most of the students, feeling very awkward in the topics, were not sure how to respond to their classmates during the conversation. When they eventually joined the conversation, it suddenly stopped without any reactions, which frustrated some students to go on next time. Some students managed to begin a new topic, but it did not last long either.

Thirdly, owning to the large total number of the messages each day, most of the students found it hard to know when the conversation began and what has been said, for the mobile phone contains a very small number of the messages on the same screen. Scrolling up and down repetitively to find the previous messages made some students lose patience and quit the conversation.

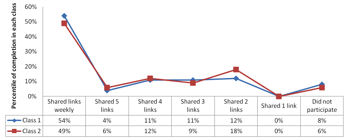

Voice Message

Similar to the text message task, students were supposed to send daily audio messages including at least ten non-repetitive notional English words—non-repetitive words in one’s own message and other students’ messages. Based on the survey, 85% of the students considered the voice message task easy or very easy and 15% of them found the task difficult. Echoing the text message task, only 10% of the student completed the task; 54% finished half or more than half of the task; 36 % of the students finished less than half of the task or didn’t participate (see Table 3). The reasons for not finishing most of the voice message task are as follows.

Table 3

Completion of voice message task

| Completed | Finished 30 days | Finished half | Finished less than half | Finished 3 days | Did not participate | |

| Number of students | 6 | 10 | 22 | 12 | 5 | 4 |

| Percentage | 10% | 17% | 37% | 20% | 9% | 7% |

First, most students, no matter how much of the task they had finished, showed their concern in the mobile phone data usage. Since a voice message uses more mobile data, some students, with no access to free Wifi, decided to say as little as possible to save money. Second, most of the students considered voice messages a challenge. They were afraid of making mistakes or being laughed at by their classmates. Some students pointed out that more listening to their classmates’ wrong pronunciations will be misleading, which also discouraged some students to speak up. The students also expressed their nervousness and difficulty in turning what they thought to what they spoke. Often, the well-thought sentence became broken in spoken English. Third, a large percentage of the students did not know what to say to their classmates during the conversation. They felt it was really difficult choosing a topic or responding to the topic. Fourth, the quality of the voice message was not always satisfying, which became a reasonable excuse for some students to stop talking through the voice function.

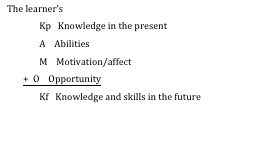

Sharing Links

Besides daily text messages and voice messages, the students were also supposed to share a weekly link relevant to English study. Since thirty-eight days contain five to six weeks, the students were only required to share five to six links altogether. According to table 6, although 92% of the students found this task easy or very easy to finish, only 56% of them finished the weekly task (see Table 4). Speaking of why the other half of the students did not finish the weekly task, less interest in doing so became the main reason. Students took this task as an optional task feeling no obligation to do it or kept forgetting to do it. The other weak reason for not sharing links, according to the students’ feedback, was that there were too many resources to decide which to share.

Table 4

Completion of sharing links task

| Shared links weekly | Shared 5 links | Shared 4 links | Shared 3 links | Shared 2 links | Shared 1 link | Did not participate | |

| Number of students | 30 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 0 | 4 |

| Percentage | 51% | 5% | 12% | 10% | 15% | 0% | 7% |

Note. Finishing 5 links can be regarded as completing the task.

Skills

As mentioned above, with the multifunctional applications of WeChat, the researcher designed the project in order to provide a space for the students to practice both their linguistic skills and communicative skills. Based on students’ feedback, the WeChat project provided great opportunities for the students to practice their English speaking, listening, reading, writing, translation, as well as communicative skills and critical thinking skills. Even though sometimes the students themselves felt they made less progress in the above-mentioned aspects, according to the researcher’s knowledge and observation about the students, they had in fact made great progress in many different ways.

Speaking

According to collected data, more than 95% of the students thought that WeChat had helped their speaking in different ways through the voice message task. Some students felt very nervous and afraid at the beginning of the project. However, with the proceeding of the tasks, students intended to take advantage of the platform to practice their spoken English and they gradually had the desire to speak English. Some expressions and phrases that the students were not sure of before had been reinforced and internalized. With the development of the conversations, the students felt more at home and more confident in this online mobile phone environment. Some quiet students had formed the habit of speaking English on the daily basis. The more advanced learners began to pay more attention to the logic and organization in their speaking. There is no doubt that the voice message task presented training and practicing opportunities to improve the EFL learner’s speaking ability.

Listening

While doing their voice message task, the students naturally had to practice their listening skills to continue the conversations. 85% of the students regarded the process helpful or very helpful. On the one hand, by listening to their classmates’ talking, they could practice their English listening skills in terms of distinguishing the accents, intonation, pronunciations, etc. in a variety of paces. On the other hand, the students also thought that the spoken language was too simple in structure and they needed more complex sentence structures to practice listening. The rest 15% of the students pointed out that the voice quality problem caused by the internet sometimes made listening difficult.

Reading

In the text message task and link sharing task, the students practiced their reading skills catering to a variety of writing styles. 95% of the students consider the project helpful to reading. With their classmates’ creative expression and a large amount of comprehensible output, the students themselves made use of the opportunity to increase their input of the English language. The ability of comprehension and the pace of reading were also practiced in the process. Some students thought it was always good to study both the simple sentences and expressions, and the more difficult ones. They agreed that by reading the mobile phone messages on a daily basis, they will increasingly build up the amount of reading and vocabulary which will improve both their receptive skills and creative skills. However, some other students considered their classmates’ language too informal and too simple to improve their reading ability.

Writing

Comparing helpfulness in EFL writing with the above-mentioned three skills, the researcher found that the students agreed strongly with the idea that WeChat group chatting was helpful for English writing skills. 93% of them thought that reading another classmate’s writing encouraged their thinking on their own writing in terms of vocabulary, spelling, expression, grammar, structure, organization, style, perspective, logic, pragmatics, and so on. Some students took notes while reading others’ comments or shared links. What’s more, continuing writing every day in the WeChat group gradually formed the writing habits among the students. The mistakes in the sentences were less frequent as time passed.

Translating

No matter which task the students did, it was unavoidable that they translated what they saw into another language. The students admitted that when they intended to say or write something in English, they had to come up with the native language first, and then translate it into English. When reading or listening to other’s conversations in WeChat group, they habitually asked for clarification if they didn’t understand. Usually the clarification turns out to be a translation instead of an explanation. However, 95% of the students thought it was helpful to translate in the WeChat project because they could learn new words, new knowledge of other fields by translating. As the students illustrated, the wrong expressions can be reduced and the errors can be avoided, which to some extent, can enhance the their confidence in language practice.

Thinking Mode

Undoubtedly, the WeChat project provided an opportunity to experience language learning by integrating it into the popular technology “in hand” through mobile phones. 95% of the students admitted that they began to think differently to prepare for the daily activities of the WeChat project. Throughout the process, the students needed to innitiate or respond to different topics, which offered them the chance to practice their comprehension, deductive and inductive thinking ability. Meanwhile, the students paid much attention to the organization of their ideas, which was the training process of their logic. The students strongly agreed that the project improved their communicative ability during the conversations. At the same time, always putting themselves into other people’s boots made the students think more critically. They began to learn about the western thinking style and shifted back and forth.

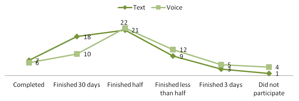

Comparing Two Classes

Because the researcher was the instructor of both the participant classes in the WeChat project, it allowed the feasibility of observing both of them in the online activities. Based on the observation and the data, both classes made more accomplishment in text message task than in voice message task (see Figure 5) due to personal or technical reasons.

Figure 5. Completion of text message task and voice message task.

By comparing the percentage of completion of different tasks between Class 1 and Class 2 (see Figure 6 to 9), the researcher found that the two classes performed similarly in the link-sharing task. For text message task, Class 1 finished more than Class 2, whereas in voice message task, Class two averagely performed better accomplishment than Class 1. By reading the text message and voice message records, it was hard for the researcher to tell the differences between the achievements of the tasks yet.

Figure 6. Completion of text message task of Class 1 and Class 2.

Figure 7. Completion of voice message task of Class 1 and Class 2.

Figure 8. Completion of sharing links task of Class 1 and Class 2.

Learners’ Perception of Others

The researcher intended to design the WeChat project as a learner-centered activity. In working through the tasks, the students had inquiries and confusions. They could reach out to their classmates, the teacher and other resources to solve the problems. During what they had experienced, the students had also obtained their own perceptions on their classmates, the teacher and the role that technology played.

Classmates’ Role

Psychologically and emotionally, the students considered their classmates friends and an audience in the WeChat project. They spoke highly of their classmates because without classmates, they would be talking alone without any responses. A majority of the students felt comfortable to talk owing to their classmates. More familiar topics and stories could be shared. When they needed emotional support, they were also able to turn to their classmates. They provided each other with help and shared a lot. The affective connections between the students and their classmates played a positive, invisible role to assist the learners to participate in the project tasks with less stress or pressure. Since they were very familiar with each other, some topics were undertaken in an easier and more natural way.

Practically and academically, the EFL practice in the WeChat project would not have been possible without the participation of the students. The students regarded their classmates as information providers, listeners, communicators, and collaborators. In the process of practicing English language skills, students provided information for each other and learned from each other. They tended to discuss, interact, make progress together and they needed to interact to keep the conversation going. Sometimes, they solved problems together in the WeChat group. If there were mistakes, the classmates might help correct them. The WeChat project students highly regarded that their classmates played a leading role in the project.

Teacher’s Role

The WeChat students assumed that the teacher should be a monitor, supervisor, leader, organizer, facilitator and the project initiator. They thought that in the process of the project, the teacher should check the ongoing process of the project, provide necessary advice or suggestions, make changes if necessary, guide or provide instructions when needed, etc. Some students suggested the teacher correct their mistakes during the conversations. They also proposed that the teacher join all the conversations and interactions with the students. However, some students were more comfortable when the teacher was not in the WeChat group. They thought the learners should take the leading role, whereas the teacher should only be an observer. In general, most students considered the project well-organized, the instructions for the task clear but they held different opinions about whether the teacher should participate in the conversations or not.

Technology

Since this is the students’ first time to systematically use their mobile phones to practice English language skills, their perception and feedback on the WeChat group was important to the researcher to understand more about this mobile phone EFL learning process. Typically, the students use mobile phones very frequently in their school life. When they were asked if the WeChat project was time consuming to them, 93% of them regarded it as reasonable time or not time consuming at all. In terms of the amount of time that students spent on WeChat project, 85% of the students spent less than an hour on WeChat project. The rest of the students spent 1 to 3 hours on it. Although 8 out of 59 students consider 38 days too long for the project, the rest of the students all agreed that the time length of the project was reasonable or needed to be longer. 61% of the participants showed their strong will of continuously using this mobile-based EFL platform on a daily basis; 35% of students expressed their willingness to go on using it occasionally; 4% of them decided to drop out of the project.

Implications

The aim of the study was to examine the learner’s participation in a mobile phone-based EFL learning environment and its effectiveness and potential. The positive findings seemed to outshine the negative sides. The Thirty-eight-day mobile phone project has ended already, but more inspirations and thoughts came out with the analysis of the data. Along the process, both the students and the teacher met some intended or unintended drawbacks. Although overall it was a meaningful experience for most of the students, there were student-related, teacher-related and technology-related obstacles. It is beneficial for the researcher to learn about it for the future improvement. Meanwhile, it has profound implications for future research related to CALL. Surprisingly, the project created a more flexible by-product which is still in use now by the previous project students.

Problems

Students

As for the student-related problems, according to the findings and the teacher’s observations, the conversation topics are more focused on the students’ daily activities with a lack of academic discussions. This is mainly because of the relatively low English proficiency of the students. What’s more, conversations are occasionally ignored because of many people talking at the same time. Since most of the time, the students attended the same classes, the WeChat topics are limited. Or, conversations directed to other fields are very fast because of the different responses of the students or no response at all. To people who jump into the conversations later, it is difficult for them to trace back to the original topic. Most students indicated that it would be easier and more convenient if certain topics were set for them from time to time, which accorded with Warschauer (2006) that the chosen topics have immense impact on the nature of the goal-oriented conversations.

Furthermore, the English language that the students usually use is informal in both spoken and written forms, along with a lot of non-standard Chinglish (Chinese-English), which makes it problematical to make progress. It shows slight difference from what Warschauer (2006) stated, where “computer-mediated communication tends to fall in the middle of the continuum of more formal communication (as often featured in writing) and informal communication (as often feature in speech)” (p. 209). Besides, the mistakes and redundancy are unavoidable along the conversations with the attempt of using more “new syntactical patterns or lexical chunks” and studying “incoming messages and carefully to plan responses” (Warschauer, 2006, p. 209). It created some non-standard or wrong English expressions prevailing in the conversations, such as “go back New Campus”, “trust in me”, “do you in downtown now?” and the like. Though the number of mistakes were few, it is still a concern to the audience that they would pick up some of these kinds of errors.

Except for the language skill problems, students shared their drawbacks in what to say and how to react to other’s comments. Such deficiency in communication hindered the smoothness and meaningfulness of the conversations. Like some other CALL studies, the hypothesis of the effectiveness of CALL in communicative skills had to be carefully investigated in depth (Beatty, 2013; Chapelle, 2006; Egbert, 2005; Warschauer, 2006).

Besides, comparing the observations of the two classes, the researcher found some differences. For instance, the cultural backgrounds of the students are a little different between Class 1 of Mongolian English Education majors and Class 2 of the Business English students. In the process of the project, Class 1 seemed more cooperative and looking forward to learning more through the process. Class 2, however, seemed less interested and put less effort into the project. Comparatively speaking, Class 1 had more willingness and motivation to do the project even though they naturally had their difficulties and confusions, but Class 2 seemed to be more pushed by the group rules, although there were exceptions in class. The different attitudes were mainly related to the individual variables (Chapelle & Jamieson, 1986) such as his or her personality, time and energy, teacher’s role, the access to the technology and the device (Rahimi & Fatemeh Hosserini K., 2011).

Technology

Technology, as many studies have found, is a two-sided tool (see Beatty, 2003; Chapelle, 2001, 2005; Chapelle & Jamieson, 1986; Egbert, 2005; Warschauer & Kern, 2000). It can be helpful in many ways, and it can also be frustrating because of the problem brought out by the process of using technology (Kern, 2006; Nunan, 2006; Warschauer, 1996). Brown (2007) discussed the technology failures caused by “either hardware or software problems” when “something fails in the fragile links between preparation and delivery” (p. 201). In the WeChat project, especially the voice message part, for most of the students who did not finish their task, the major cause of the problem was the unexpected unclear voice recording system. They were not satisfied with the clearness of the recorded voice and they were also confused by other students’ unclear recordings. This shows the downside of technology in CALL where teachers have to be careful designing and facilitating the process in case of a breakdown of the internet or other technical problems (Kern, 2006; Nunan, 2006; Warschauer, 1996).

Besides, because of the large number of students in the same group, the average number of conversations each day was about two hundred. It means that besides the non-WeChat project messages, the students had to face about 200 messages each day. The inexperienced users of WeChat who had no knowledge of the message alert function were annoyed by the messages popping up constantly throughout the day and even deep into the night when some students tried to finish their task of that day (Warschauer, 2006). One of the biggest obstacles for the students was that there was no accessible public Wifi that they can use to do the tasks for free, which meant that the students themselves had to pay through their mobile phone data package. This was a big problem for most of the students because it was costly if they wanted to fully participate the project.

Teacher

Since the WeChat project was initially designed as a mobile phone online assignment when the teacher was abroad to take an intense international training course for a month. The teacher had worked on the procedure, requirements, evaluations and some problems that might occur before the actual start of the project, however, the teacher didn’t expect the common inconvenience of Wifi to most of the students, the coarse quality of the voice recording, the late-night conversations that annoyed the students, and the students’ expectations for a lot more participation from the teacher. As Chapelle (2008) noted, teachers’ knowledge and skills in technology, to some extent, will influence the effectiveness of a technology-based learning project.

One more thing is that the teacher was planning to monitor the conversations whenever it happened so that she could provide advice for the students. However, when the teacher was participating in the training course in another country for only two days, she knew it was impossible to be an on-the-spot monitor or supervisor because the schedule of the training course was so intense that the trainees had a lot work to do even after the in-class training every day. Fortunately, the teacher could managed to observe the whole process during the tea breaks between different sessions of the training, but this observing behavior without a lot participation in the WeChat conversations made the students feel lost. The teacher should take responsibility for the decentralizing topics that frustrated some beginners and made them drop out of some ongoing conversations (Warschauer, 2006).

Although, for the teacher, the WeChat group presents a means for the student to be an autonomous learner without too much interference, actually “most learners do not know how to work autonomously to their best advantage. Instead, they need guidance from appropriately designed learning materials and teaching” (Chapelle, 2008, p. 612). In fact, a learner’s autonomy mostly depends on the teacher’s attitudes, beliefs and their facilitation (Warschauer & Kern, 2000). In other words, “adaptive instruction” is needed in this respect, where changes are made according to when and what the students need (Jonassen & Grabowski, 1993, p. 35). As Egbert (2005) pointed out, “it is not just the technology or the language that is important, but a whole learning environment system that teachers can create with their students” (p. 4). The students in the WeChat project showed their willingness to have the teacher involved in all the conversations. In other words, the teacher is not limited in the role she should play and may need to be more than just a designer and an observer.

Future research

It is obvious that the mobile phone WeChat project had a lot of benefits and opportunities for reflection for both the students and the teacher. By setting up such an EFL learning environment, the students were learning by experiencing, making their own decisions within the project rules, and practicing their communicative skills which to some extent indirectly improved their cognitive ability. Right after studying the questionnaires from the students, the researcher had a short meeting with the Mongolian English Education sophomores for the following purposes.

First, the teacher considered the WeChat group a precious platform for EFL learners who had fewer opportunities to use English language like ESL learners do. Therefore, based on the natural existence of the WeChat group now and the possibility of the continuance of the English group chat, the teacher encouraged the students to go on this project voluntarily.

Second, some students have kept practicing English as their spoken language in the WeChat group even after the project was over, and they invited their counseling teacher into the group chat also. Therefore, based on the feedback from Class 1, the researcher invited two American educators, one Australian university librarian and a fourth-year student in the same university to the WeChat group. Regarding these English native speakers as assets, the teacher encouraged the students to take the opportunity to communicate freely.

Finally, the teacher gave up the rule-maker role of the group chat and let the students totally take charge. The teacher officially retired as the group leader or monitor role to be only an equal student this time. The students were encouraged to organize the WeChat conversations and other activities, and make their own decisions.

Up to now, the WeChat group has invited three English course teachers, including the researcher, the head of the department and another associate professor. The other four native speakers in the group have also taken the role of the language exemplars and cultural ambassadors, which aroused the students’ interests in learning other cultures and at the same time introducing their own culture to the audience. In this sense, the researcher will go on focusing on this group to do a longitudinal study to collect more data in order to study the effectiveness of the WeChat group as a platform of learning English as a foreign language after all these changes.

As one of the cutting-edge examples of mobile phone technology, WeChat has many similarities with other internet communicative tools. Therefore, the research can be focused on the comparisons of the most popular tools and integrate one or two of them into the English curriculum or extracurricular activities. Thus, mobile phone-based EFL learning may expand to become a necessary part of EFL teaching and learning in the future. Meanwhile, with the more frequent and closer exchange among different countries and regions, more research can be conducted between different regions, countries or cultures. Then learning EFL is not simply learning in the learner’s own contexts, but learning with people from the authentic English contexts.

Reference

Barson, J., Frommer, J. & Schwartz, M. (1993). Foreign language learning using e-mail in a task-oriented perspective: Interuniversity experiments in communication and collaboration. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 2 (4), 565-584.

Beatty, K. (2003). Computer-assisted language learning. In D. Nunan (Ed.), Practical English language teaching (pp. 247-266). New York: McGraw-Hill Contemporary.

Beatty, K. (2013). Teaching and researching: Computer-assisted language learning. (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Brown, H. D. (2007). Principles of language learning and teaching. (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Chapelle, C. (2001). Computer applications in second language acquisition: foundations for teaching, testing and research. New York: Cambridge University.

Chapelle, C. (2005). Computer-assisted language learning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 743-755). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Chapelle, C. (2008). Computer-assisted language learning. In Spolsky, B. & Hult, F. M. (Eds.). The handbook of educational linguistics (pp. 585-595). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Chapelle, C. & Jamieson, J. (1986). Computer-assisted language learning as a predictor of success in acquiring English as a second language. TESOL Quarterly, 20(1), 27-46.

De Szendeffy, J. (2005). A practical guide to using computers in language teaching. MI: University of Michigan Press.

Dörnyei, Z. (1994). Motivation and motivating in the foreign language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 78(3), 273-284.

Dörnyei, Z., Csizér, K., & Németh, N. (2006). Motivation, language attitudes and globalisation: A Hungarian perspective. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Dörnyei, Z. & Schmidt, R. (2001). Motivation and second language acquisition. (Tech. Rep.). Honolulu: University of Hawaii, Second Language Teaching and Curriculum Center.

Egbert, J. (2005). Call essentials: Principles and practice in CALL classrooms. Alexandria, VA: TESOL.

Egbert J., Chao, C., & Hanson-Smith, E. (2007). Introduction: Foundations for teaching and learning. In J. Egbert & E. Hanson-Smith (Eds.), CALL environments: Research, practice, and critical issues (2nd ed.) (pp. 1-14). Alexandria, VA: TESOL.

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: the role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Jia, G. (2007). Computer-assisted language learning: Theory and practice. Beijing: Higher Education Press.

Jonassen, D. H., & Grabowski, B. L. (1993). Handbook of individual differences, learning, and instruction. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kern, R. (2006). Perspectives on technology in learning and teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 40 (1), 183–210.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2000). (2nd ed.). Techniques and principles in language teaching. UK: Oxford University Press.

Munca, D. (2008). Turning blogs into cognitive tools. The Essential Teacher, 5 (2), 37-39.

Nunan, D. (2006). TESOL’s most daring ideas. Paper presented at Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Tampa, FL.

Oxford, R. (Ed.). (1996). Language learning motivation: Pathways to the new century. (Tech. Rep. #11). Honolulu: University of Hawaii, Second Language Teaching and Curriculum Center.

Rahimi, M. & Fatemeh Hosseini K. S. (2011). The impact of computer-based activities on Iranian high-school students’ attitudes towards computer-assisted language learning. Procedia Computer Science, 3, 183-190.

Richardson, W. H. (2006). Blogs, wikis, podcasts, and other powerful web tools for classrooms. Corwin Press.

Schmidt, R., Boraie, D., & Kassabgy, O. (1996). Foreign language motivation: Internal structure and external connections. In R. Oxford (Ed.), Language learning motivation: Pathways to the new century (pp. 14-88). Honolulu: University of Hawaii, Second Language Teaching and Curriculum Center.

Shoaib, A. & Dörnyei, Z. (2005). Affect in lifelong learning: Exploring L2 motivation as a dynamic process. In P. Benson, & D. Nunan (Eds.), Learners’ stories: Difference and diversity in language learning (pp. 22-41). UK: Cambridge University Press.

Spolsky, B. (2004). Language policy: Key topics in sociolinguistics. UK: Cambridge.

Spolsky, B. (2007). Introduction: What is Educational Linguistics? In B. Spolsky, & F. M. Hult, (Eds.). The handbook of educational linguistics. Blackwell Publishing.

Tyler, R. W. (1986). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

Warschauer, M. (Ed.). (1995).Virtual connections: Online activities and projects for networking language learners. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Second Language Teaching and Curriculum Center.

Warschauer, M. (Ed.). (1996). Telecollaboration in foreign language learning. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Second Language Teaching and Curriculum Center.

Warschauer, M. (2006). On-line communication. In R. Carter & D. Nunan (Eds.), Teaching English to speakers of other languages (8th ed., pp. 207-212). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Warschauer, M. & Kern, R. (2000). Network-based language teaching: concepts and practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wen, Q. (2012).中国外语类大学生思辩能力现状研究 [English majors in China: Critical thinking studies]. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

This academic article was accepted for publication in the International HETL Review (IHR) after a double-blind peer review involving two independent members of the IHR Board of Reviewers and one revision cycle. Accepting editors: Dr Amy Lee, University of Minnesota and Dr Rhiannon Williams, University of Minnesota

Suggested citation:

Wuyungaowa. (2015). Engaging EFL Learners through WeChat: A Mobile Phone-Based EFL Learning Project in China. International HETL Review, Volume 5, Article 5. https://www.hetl.org/engaging-efl-learners-through-wechat-a-mobile-phone-based-efl-learning-project-in-china

Copyright 2015 Wuyungaowa

The author asserts her right to be named as the sole author of this article and to be granted copyright privileges related to the article without infringing on any third party’s rights including copyright. The author assigns to HETL Portal and to educational non-profit institutions a non-exclusive licence to use this article for personal use and in courses of instruction provided that the article is used in full and this copyright statement is reproduced. The author also grants a non-exclusive licence to HETL Portal to publish this article in full on the World Wide Web (prime sites and mirrors) and in electronic and/or printed form within the HETL Review. Any other usage is prohibited without the express permission of the author.

Disclaimer

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and as such do not necessarily represent the position(s) of other professionals or any institution. By publishing this article, the author affirms that any original research involving human participants conducted by the author and described in the article was carried out in accordance with all relevant and appropriate ethical guidelines, policies and regulations concerning human research subjects and that where applicable a formal ethical approval was obtained.