HETL Note: Dr. Marilla Svinicki is the senior author (together with co-author Dr. Wilbert McKeachie) of the latest edition of McKeachie’s Teaching Tips: Strategies, Research, and Theory for College and University Teachers, published in 2010 (Cengage Learning). In Teaching Tips, Dr. Svinicki asserts that effective teaching requires today’s teacher to possess a deep appreciation for and understanding of the latest theory and research on teaching and learning and that it is through this theoretical foundation that the teacher will be able to more readily adapt to new situations and develop his/her own methods for effective teaching. HETL interviewed Dr. Svinicki via Skype to gain a deeper insight into this view.

Bio: Dr. Marilla Svinicki is a Professor and Area Chair (Human Development, Culture and Learning Sciences) in the Department of Educational Psychology and the retired director of the Center for Teaching Effectiveness at the University of Texas at Austin (USA). She currently teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in instructional psychology, learning, cognition and motivation. Her research interests include application of principles of learning to instruction in higher education and development of faculty and graduate students as teachers. In 2007, she received a lifetime achievement award from the American Educational Research Association’s (AERA) Special Interest Group on Faculty Evaluation. In 2011, she received the Texas Exes Teaching Award at the University of Texas at Austin. Dr. Marilla Svinicki was the editor-in-chief of New Directions for Teaching and Learning and is on the Board of Directors at The IDEA Center. She served twice as President of the POD Network. Dr. Svinicki may be reached at [email protected]

Bio: Dr. Marilla Svinicki is a Professor and Area Chair (Human Development, Culture and Learning Sciences) in the Department of Educational Psychology and the retired director of the Center for Teaching Effectiveness at the University of Texas at Austin (USA). She currently teaches undergraduate and graduate courses in instructional psychology, learning, cognition and motivation. Her research interests include application of principles of learning to instruction in higher education and development of faculty and graduate students as teachers. In 2007, she received a lifetime achievement award from the American Educational Research Association’s (AERA) Special Interest Group on Faculty Evaluation. In 2011, she received the Texas Exes Teaching Award at the University of Texas at Austin. Dr. Marilla Svinicki was the editor-in-chief of New Directions for Teaching and Learning and is on the Board of Directors at The IDEA Center. She served twice as President of the POD Network. Dr. Svinicki may be reached at [email protected]

Patrick Blessinger and Krassie Petrova

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Learner-Centered Teaching

Marilla Svinicki

University of Texas at Austin

HETL: Dr. Svinicki, the main idea of your book centers on the need to create a learner-centered environment in and out of the classroom. You make the statement that “What is important is learning, not teaching.” Are you saying that good teaching does not matter?

Marilla Svinicki [MS]: What I mean by that statement is that the purpose of teaching is to help learning happen. Teaching is not an end in and of itself. Even the best teacher cannot learn things for the students. Current learning theory places the control of learning in the hands and heads of the students. So what we have to focus on as teachers is not what we are doing. Instead we have to focus on what the students are doing to learn. In a learner-centered environment, it is the learners’ actions that are the drivers of learning. So as teachers we try to provide opportunities for that active involvement in learning to occur. For example, learners might be invited to set goals for a learning session, to choose among activities that would help them meet those goals, to evaluate their own progress, and give feedback to the instructor about what they do and do not understand. The instructor would then use that feedback to offer further suggestions or activities that might target misunderstandings. Thus the instructor is acting in support of the learners rather than directing them.

HETL: Dr. Svinicki, you say that “Most student learning occurs outside the classroom.” If this is so, then does good teaching make that much of a difference in student learning?

MS: In every novice/expert relationship, the expert has to create the environment that will facilitate learning, even if that environment is not under their direct control. Students are not in a position to decide on what they should learn. They are not prepared to suggest what the teacher has to offer, so good teachers probably have their impact in setting up the learning objectives, materials, activities and strategies that support student learning, even when it actually happens outside the classroom. I think that students do not do much consolidation of learning during class time. There is too high a cognitive load going on. It is not until they get actively into studying (which does not occur in most classrooms unless active learning opportunities are built into the session) that the actual learning occurs.

HETL: Dr. Svinicki, it seems that there has been, traditionally, a divide between teaching and research at many universities because the reward system for faculty has favored them doing research over good teaching. Are teaching and research incompatible? Can one be both a great teacher and a great researcher?

MS: Yes, the reward system in research institutions does tend to favor activities that are cutting edge research, and yet that is not because teaching and research are incompatible. Rather, research is what makes the institution’s reputation, which allows it to attract students, supporters, and mostly money. But, of course, that is not what you asked. You want to know if I think research and teaching are incompatible. The only place where they are incompatible is in the zero sum game of time. The more you have to do of one, the less time you have to devote to the other. Really good teachers can be found both in the classroom and the research lab, teaching every time they interact with students. And really good researchers often find that when they are trying to explain a concept to students, they come up with ideas about moving the field forward. If we had all the time in the world, most faculty would choose to be good at both.

HETL: Dr. Svinicki, you talk about motivational theories in your book. Some say that it is not the role of faculty to be motivators. Is it important for faculty to understand how students are motivated? In other words, who is ultimately responsible for student learning? Is it the student or the teacher or the institution?

MS: Motivation, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder in current psychological theory. The motivating properties of a situation depend on the way the learner interprets what is going on. Two students can be exposed to the same educational situation and one will find it motivating and the other will not. However, that does not absolve the instructor from trying to tap into the sources of motivation that psychology has laid out for him or her. There is a lot we know about how to structure an environment to increase the probability that students will find it motivating.

For example, one interesting finding in the research literature is that students are very attuned to what we call the classroom goal structure. The goal structure refers to whether the instructor is primarily aiming for deep mastery of a topic or surface understanding, among other goals. I want to emphasize that either of these goals are legitimate for college classes. Some courses target a broad understanding while others aim for a much deeper but narrow learning. The goal structure is revealed by the way different activities are “valued” in the classroom (for example, how much time is devoted to each activity, which count in the grading structure or how the instructor interacts with the students, praising one action while ignoring others). Each of these characteristics is considered to be part of the motivational structure of the class. Students use these cues to determine what goals the instructor thinks are important.

If I were to give you three specific ideas that would support student motivation, I would say, first, take advantage of what is already motivating to the student by giving choices so that students will be able to work in ways that fit their own needs, thus putting them in charge of their own motivation. Second, I would suggest changing the goal structure of the class toward mastery by changing the meaning of making mistakes. Instead of viewing mistakes as being a bad thing, mistakes can be viewed as opportunities to correct misunderstandings by allowing students second chances to fix up their mistakes or explain how they came to make them. Finally I would suggest that we remember that students need to hear what they did right as well what they did wrong so that they can develop the belief that they are capable of learning.

HETL: Dr. Svinicki, you also talk about teaching students from different backgrounds. Some may also say that the main duty of teachers is to teach the content, irrespective of the expectations of the students. How would you respond to that view?

MS: I disagree strongly with that view. Our job is to help students learn, not fill them up with the latest content. The problem that usually brings this up is that each discipline is moving so quickly into new areas that faculty are convinced that every finding is important to everyone or needs to be understood before other findings are understood. I think we have to realize that it is no longer possible to be a fully informed adult; each of us must carve out what matters to us most and focus on that. So to expect all students to find value in everything we have to offer is naïve. Our strength is in recognizing and exploiting the differences in interest that eventually lead to wonderful new questions that would never have occurred to us if everyone knew what everyone else did and therefore never had a new idea or perspective.

MS: I disagree strongly with that view. Our job is to help students learn, not fill them up with the latest content. The problem that usually brings this up is that each discipline is moving so quickly into new areas that faculty are convinced that every finding is important to everyone or needs to be understood before other findings are understood. I think we have to realize that it is no longer possible to be a fully informed adult; each of us must carve out what matters to us most and focus on that. So to expect all students to find value in everything we have to offer is naïve. Our strength is in recognizing and exploiting the differences in interest that eventually lead to wonderful new questions that would never have occurred to us if everyone knew what everyone else did and therefore never had a new idea or perspective.

HETL: Dr. Svinicki, you talk about active and collaborative learning. How possible is it to create an active and engaging learning environment for very large classes, say for a class size of 300?

MS: Well, active and engaging are not synonymous, so I cannot give you a single answer to solve everyone’s dilemma. While it is definitely the case that collaborative learning is the most common way we think of using to produce engagement, active does not have to mean interacting with someone else. I can be active sitting by myself in my office reading a book – If I am actively reading that book. The same is true in large groups. Activity can be done by large or small groups or by an individual. However, sometimes what people have students do collaboratively is not really engaging them in learning. The activity we want is for learners to ask and answer questions about what they are learning. One of the most fruitful active learning strategies is for students to explain their understanding to one other person. You can certainly do that in classes of any size. Even rhetorical questions trigger thinking if the speaker would stop talking for a while and let the students think, while rote responding in a group activity does not. I think it is the type of questions or the problems that a teacher poses that foster active learning even in large classes. Of course, not all the students in a large class respond to the teacher’s questions with a burst of thinking, but that is not confined to a large class; it happens in small ones, too.

Now about engaging – I know that many faculty bristle when I suggest that teachers are performers, but it is true. Mostly what students mean by engaging is enthusiastic and interested and bringing the content of the course into the real world by connecting it to the students’ own experience. If you cannot do that about your topic, then you are not an expert after all. For example, “engaging” in a large class might mean bringing into the classroom real issues that are the current topic of discussion in the field and how those issues might impact student lives now or in the future. We now have the means to electronically “engage” students in classes of all sizes. Posing a question and inviting students to use “clickers” to express their understanding or their opinion is a wonderful way of engaging students. My own students become very animated when we do this and reveal that not everyone has the same opinion. “Engaging” might mean inviting students in large classes to bring their own questions to class when something they have seen or read looks like it might be related to the course topic. This can easily be done through online discussion boards or email to the instructor, who can then bring the topic to class. “Engaging” might mean revealing our own individual thinking and motivations about the field, becoming a person to the students rather than just a source of information. None of these suggestions need to take a lot of time or effort, but they do change the focus of the course from just listening to “engaging.”

HETL: Dr. Svinicki, some faculty have to deal with student problems such as emotional problems and disruptions in the classroom. How can faculty be expected to deal with such situations if they have not received any training in these areas?

MS: They should not, and at most institutions they are not expected to intervene. Most forward thinking institutions have individuals trained to work with students who are having difficulties, if they could just get in touch with them. Perhaps that is the best thing the instructor can do: get the student connected with the trained professional. If a student appears to be slipping, they often really just want someone to care enough to do something, even if it is refer them to someone who can help and then follow up later to see if they are ok. Being a concerned adult may be all we have to do, and surely we are all up to that task.

HETL: Dr. Svinicki, you also talk about experiential learning (EL) in your book. How practical is it to apply EL? Should EL be a part of every course?

MS: Absolutely! You may not mean what I mean when you say experiential learning. In reality all learning is experiential. We do something and get feedback from the situation. Therefore all courses and every part of a course should involve “experiential learning.”

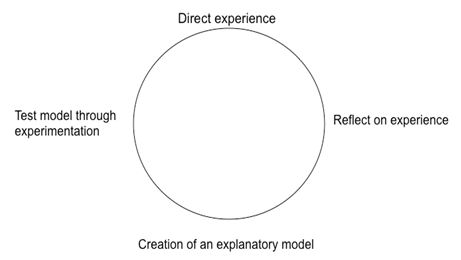

However, you may mean the more structured experiential learning models such as those based on Kolb’s experiential learning cycle; for example problem-based learning, where students work to explore and solve problems based on real situations. It is used a lot in science and medical training. Another type of experiential learning is service learning, where students work in real world settings on problems that confront the agencies and communities in which they are placed. I do not think that structured experiential learning is possible or even appropriate for all classes and all levels of students. I think it is particularly important when students are at a level of wanting to integrate what they know. I do not believe absolute beginners should have that kind of advanced experiential learning because I am not convinced they even know what they are supposed to be learning. It takes some level of prior knowledge to benefit fully from an experience. There are small experiences that everyone can benefit from and those are something we should strive for in all courses. This is related to our earlier discussion about active learning.

However, you may mean the more structured experiential learning models such as those based on Kolb’s experiential learning cycle; for example problem-based learning, where students work to explore and solve problems based on real situations. It is used a lot in science and medical training. Another type of experiential learning is service learning, where students work in real world settings on problems that confront the agencies and communities in which they are placed. I do not think that structured experiential learning is possible or even appropriate for all classes and all levels of students. I think it is particularly important when students are at a level of wanting to integrate what they know. I do not believe absolute beginners should have that kind of advanced experiential learning because I am not convinced they even know what they are supposed to be learning. It takes some level of prior knowledge to benefit fully from an experience. There are small experiences that everyone can benefit from and those are something we should strive for in all courses. This is related to our earlier discussion about active learning.

HETL: Dr. Svinicki, course evaluations by students are not without controversy yet seem to be used more and more at universities. How effective are they in your view? And who should use them and for what purpose?

MS: There is so much research on this topic that it’s difficult to summarize it in the space allotted. So I will just offer my perspective and invite the readers to consult the multiple articles that have attempted to do that very summarizing. In my view student evaluations are the most reliable and consistent source of data that we currently have on teaching at the postsecondary level. Many researchers have shown that student evaluations across several semesters and several courses provide a fairly stable view of student perspectives on teaching. They are especially valuable for improving one’s own teaching, providing they are not considered the absolute end of information that can be gathered. Data should be gathered throughout the semester rather than solely at the end. We always say that they are best used for formative evaluation and as one of an array of data sources when evaluating teaching for summative evaluation.

HETL: Dr. Svinicki, you talk about the need to teach ethics. Some may contend that it is not the role of teachers to teach ethics. Others may argue that it serves no practical purpose because the examples of recent ethical breaches in the news show it has little effect. How would you respond to that?

MS: How can people be blind to the fact that every teacher is ALWAYS teaching ethics just by being there and interacting with the students? Their ethics are there for all to see every day in class or in office hours or even in the choices we make about how the course is structured. So some may think it is not our role to teach ethics, but it is impossible not to at least model our ethical values in all we do. We teach what and who we are by the way we behave in the day to day workings of our classes.

HETL: What would you want readers to take away from your book?

MS: Perhaps the most important thing is that the book illustrates that one can continue to learn about teaching by reading both the literature and the students. The literature, because there is literature on teaching that is grounded in research on learning and motivation, allowing us to find practices that can help us be better teachers. The students, because as we said at the beginning of this interview, it is what the students do that matters. Being aware of what the students in one’s class are doing is the best source of information to help us be better teachers.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Further reading: see endnotes.

Interview date & place: 1 October 2011 via Skype

HETL interviewers: Patrick Blessinger and Krassie Petrova

Copyright © [2011] Marilla Svinicki and International HETL Association

Suggested citation:

Svinicki, M. (2011, October 1). Learner-Centered Teaching: An HETL interview with Dr. Marilla Svinicki/Interviewers: Patrick Blessinger and Krassie Petrova. Published in The HETL International Review, Volume 1, Article 11. Retrieved from https://www.hetl.org/interview-articles/learner-centered-teaching

Endnotes:

Kolb. D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as a source of learning and development. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Wilkerson, L. & Gijselaers, W. H. (Winter, 1996). Bringing problem-based learning to higher education: Theory and practice. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 68. SF: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Simons, L . & Cleary, B. (2006). The Influence of service learning on students’ personal and social development. College Teaching, 54(4), 307-319.