HETL Note:

In this academic article, authors Drs. Bruce K. Blaylock, Tal Zarankin, and Dale A. Henderson, discuss the limitations and challenges of the traditional structure of higher education – they call this model of higher education the factory model. The authors propose a new structure for higher education institutions that center on learning cohorts, team teaching, and professional learning communities – they call this model of higher education the cohort model. The authors make several recommendations that universities and colleges can use to help them adapt their structures to be more like medical clinics where students’ needs are first assessed and then faculty and staff collaborate to provide a more holistic and integrated way to improve students’ learning.

Author bios:

Bruce K. Blaylock, Professor Emeritus Radford University, earned a BBA in Quantitative Analysis from Ohio University, an MBA from Auburn University, and a Ph.D. in Decision Sciences from Georgia State University. His research interests evolved during his career from quantitative decision making to leadership and strategic direction in higher education in art as a result of serving ten years as Dean of the Ancell School of Business at Western Connecticut University and the College of Business at Radford University. His research has appeared in Decision Sciences; R&D Management; Journal of Educational Research; Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics; Journal of Management Education, The Journal of Learning in Higher Education, and others. Although retired from Radford University, he remains active as a consultant to organizations like Volvo Heavy Trucks, The Radford School of Nursing, and Roanoke, Virginia, City Government.

Bruce K. Blaylock, Professor Emeritus Radford University, earned a BBA in Quantitative Analysis from Ohio University, an MBA from Auburn University, and a Ph.D. in Decision Sciences from Georgia State University. His research interests evolved during his career from quantitative decision making to leadership and strategic direction in higher education in art as a result of serving ten years as Dean of the Ancell School of Business at Western Connecticut University and the College of Business at Radford University. His research has appeared in Decision Sciences; R&D Management; Journal of Educational Research; Journal of Leadership, Accountability and Ethics; Journal of Management Education, The Journal of Learning in Higher Education, and others. Although retired from Radford University, he remains active as a consultant to organizations like Volvo Heavy Trucks, The Radford School of Nursing, and Roanoke, Virginia, City Government.

Tal Zarankin is an Associate Professor of Management at Radford University’s College of Business and Economics. He received his law degree at the College of Management, Israel in 1992, and practiced law for six years in a private law firm in Tel-Aviv. He completed his Ll.M. in Alternative Dispute Resolution at the University of Missouri School of Law, in 2003. He received his Ph.D. in Business Administration in 2008 at the University of Missouri, specializing in the area of organizational behavior. His main research interests are in the field of conflict management, individual decision-making, and the impact of cross-cultural differences on management outcomes.

Tal Zarankin is an Associate Professor of Management at Radford University’s College of Business and Economics. He received his law degree at the College of Management, Israel in 1992, and practiced law for six years in a private law firm in Tel-Aviv. He completed his Ll.M. in Alternative Dispute Resolution at the University of Missouri School of Law, in 2003. He received his Ph.D. in Business Administration in 2008 at the University of Missouri, specializing in the area of organizational behavior. His main research interests are in the field of conflict management, individual decision-making, and the impact of cross-cultural differences on management outcomes.

Dale A. Henderson is a Professor of Management at Radford University. He received his Ph.D. in Management from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in 1998 with a primary emphasis on Strategic Management and Entrepreneurship. He received an MBA from Radford University and a Bachelor of Science in Finance and a Bachelor of Science in Marketing Education from Virginia Tech. Dr. Henderson is primarily responsible for teaching Strategic Management and Entrepreneurship courses. His publications can be found in periodicals such as Journal of Applied Business Research, Journal of Accountancy, Academy of Strategic Management Journal, Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, Journal of E-Commerce, and Academy of Strategic and Organizational Leadership Journal. In addition to his many academic accomplishments, Dr. Henderson has experience in the field of project management and technical recruiting.

Dale A. Henderson is a Professor of Management at Radford University. He received his Ph.D. in Management from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in 1998 with a primary emphasis on Strategic Management and Entrepreneurship. He received an MBA from Radford University and a Bachelor of Science in Finance and a Bachelor of Science in Marketing Education from Virginia Tech. Dr. Henderson is primarily responsible for teaching Strategic Management and Entrepreneurship courses. His publications can be found in periodicals such as Journal of Applied Business Research, Journal of Accountancy, Academy of Strategic Management Journal, Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, Journal of E-Commerce, and Academy of Strategic and Organizational Leadership Journal. In addition to his many academic accomplishments, Dr. Henderson has experience in the field of project management and technical recruiting.

Restructuring Colleges in Higher Education around Learning

Bruce Blaylock, Tal Zarankin, and Dale Henderson

Radford University, USA

Abstract

This paper suggests changes to the traditional approach and structure of colleges in higher education. We use the factory metaphor to describe traditional universities, where students are treated like raw materials that enter the plant, are independently processed in a standardized way, and shipped out the door upon completion. We suggest colleges and universities should rather resemble a medical clinic in which teams of physicians (faculty), nurses, and support staffs assess the needs of patients (students) and collaborate on ways to provide a holistic solution to improve patients’ overall wellbeing. We discuss the benefits of this new structure based on supporting literature from various disciplines.

Keywords: student learning cohorts, teaching teams, professional learning communities

Introduction

Consider how professions have changed over time as depicted by popular TV shows. During the 1960s, the legal profession was represented, in the United States, by Perry Mason, a lone defendant lawyer, who had all the wisdom and insight necessary to free his wrongly charged client and to get the truly guilty person to admit it on the stand. Today’s popular legal shows include Boston Legal, typified by a team of lawyers sharing knowledge and responsibility for cases. The practice of medicine was different in the 1950s and 60s, and was so represented, by the single heroic physicians Dr. Kildare or Ben Casey. Today it is Grey’s Anatomy or House with a team of physicians and nurses providing services and sharing responsibility.

Contrast that with shows about education. Welcome Back Kotter of the 1970’s or the short-run sit-com Teachers in 2007 with the lone teacher in the classroom is no different today than it was then or even one hundred or two hundred years ago, especially in higher education. The adage, “Being a professor is a lonely profession,” is usually attributed to the long hours professors spend on their research, but we submit the loneliness of the profession is perhaps greater in teaching. Professors discuss their research with one another and often collaborate on projects; but how often are college or department meetings devoted to improvements in learning?

In this paper, we discuss two main problems that stem from the current structure, culture, and functioning of higher education colleges and universities. The problems are: a lack of interdependence among teaching faculty and a focus on teaching rather than on learning.

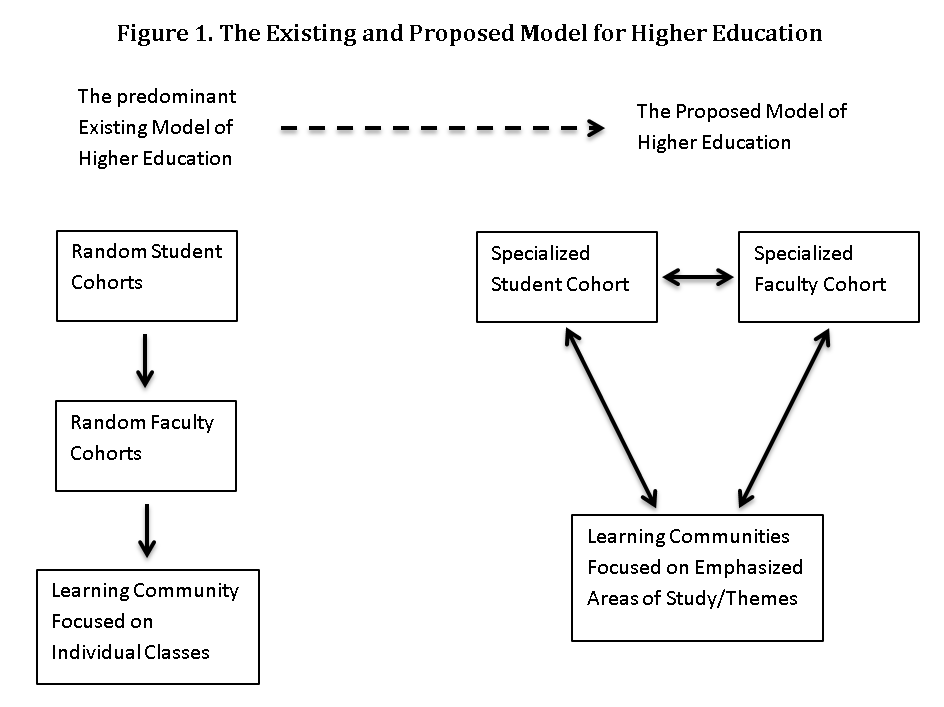

Figure 1 illustrates the shift we propose. It suggests that the existing model of most colleges is akin to a factory where random groups of students arrive at the university, are assigned professors based on personnel considerations, and participate (sometimes sporadically) in learning environments called classes. Students and professors, for the most part, operate in silos. We assert that instead, colleges should shift to a dynamic and interdependent structure (portrayed on the right side of the figure) by creating specialized and interdependent student and faculty cohorts, which will form specialized learning communities.

This paper is organized as follows: The next section describes the current state of higher education. It compares the educational process to that of factory production, and identifies two significant flaws in that approach to learning: systemic isolation of faculty within a process which would be more effective by utilizing groups or teams to approach the task; and an implicit focus on teaching rather than on learning. We draw on the work of a recognized educational theorist to establish a framework for addressing these flaws. That section is followed by our recommendation for a new organizational structure for higher education. Here we review three non-traditional approaches to effective learning and detail a different approach that we call “Learning Cohorts.” Our discussion of learning cohorts includes descriptions and responsibilities of the key players: faculty and students. Next, we recognize specific issues progressive faculty and administrators will have in implementing our recommended organizational plan. Finally, we identify several directions for future researchers to pursue.

The Current State of the Higher Education System

The Factory Metaphor

Since their early days, most comprehensive public higher education institutions focused implicitly (or in many cases stated explicitly by state legislatures) on moving students expeditiously through the system, fulfilling degree requirements, trusting that the sum of the independent experiences they receive will add up to “an education” that will yield meaningful contributions to today’s society (Arum & Roksa, 2011; Hersh & Keeling, 2013).

That mindset turned traditional college teaching to a process analogous to a factory model: raw materials (students) enter the institution and are processed at independent stations (classes). The University assumes workers (professors), operating within the curriculum guidelines, will make proper adjustments to the product (students) to assure it will be well-built at the end of the process (curriculum). Workers at the workstations have responsibility for the work done at their station, but have little, if any, sense of responsibility for defects they might identify when the product gets to them or the overall quality of the product as it exits the organization. The independent stations are linked through curriculum, but beyond requiring one station to process the raw material before another, little communication is done about the progression of learning or the quality of the product in aggregate, as opposed to individual pieces.

A traditional factory treats the product it manufactures in a linear manner. There is an input of some sort, to produce a standard pre-determined output. Most traditional comprehensive universities follow that model in that there is relatively little consideration for the unique interests, strengths, abilities, and goals of individual students. All students who enter the university are treated as one. All students must go through the same process in a linear manner to earn a degree, which is the pre-determined outcome the university sets. Students may pick their majors, minors and electives, but they go through the same process overall.

A major consequence of the factory approach is a standard and fragmented learning experience, which incentivizes students to focus on accumulating credit hours and grades in individual classes. A more appropriate approach for students would be to take classes that either complement or reinforce each other and result in a holistic learning experience (Hersh & Keeling, 2013). The later approach would enable students to integrate knowledge from different classes and acquire fundamental skills and competencies they will need when they start their careers after college (Hersh & Keeling, 2013). Indeed, scholars have recognized that an integrative learning experience, which enables students to recognize common threads among classes and learn overarching skills, is a major challenge in higher education (Taylor-Huber & Hutchins, 2004).

Another unintended consequence of the factory approach to higher education is the lack of individual attention and relationship between professors and their students. Professors in most mid-size to large universities focus, by the design of their job, on a new group of students every semester. This is much like the linear process in a factory where each factory employee treats raw materials in a very narrow aspect of the whole production process. From the students’ perspective, over the course of their four-year degree, they have very little continuity in their relationships with any given professor. Rather, students are rotated among different faculty each semester. As a result, the advice and feedback students may receive from faculty is limited in scope and built upon a limited pool of information.

Assessment in higher education, which perpetuates the status quo, is also problematic. It is standardized to large groups of students and does not help in true discovery of students’ overall learning experience of key skills applicable across different contexts (Ewell, 2013).

The data for most assessment comes mainly from the opinions of those going through the system. Assessments ask students about how well they were processed (taught), not the about outcome (learning) of the process. This is analogous to asking patients how good their doctor is—as long as they didn’t wait too long in the waiting room and the doctor’s bedside manners were satisfactory, the doctor probably gets good reviews even though the patient continually returns for treatment of the same symptoms and maladies.

Another problem related to assessment is that teachers, who are the main players in the educational setting, have traditionally not been a part of the design of the assessment process and are still largely not a part of this important process (Hutchings, 2010). Scholars have argued that professors, who are in charge of student learning, should have significant input in the design of assessment tools and processes (Banta, Griffin, Flateby, & Kahn, 2009; Hutchings, 2010).

Based on the above discussion, we identify two shortcomings associated with higher education:

- A lack of interdependence in the core structure of a professor’s job;

- A focus on teaching rather than on learning; and

Next, we address each one of these shortcomings in greater detail, and subsequently, offer potentials remedies.

Issue 1: The Lack of Interdependence in the Core Structure of Professors’ Jobs

Interdependence refers to a situation in which two or more individuals depend upon each other’s actions or inputs for achieving a desired outcome (Kim, Bhave, & Glomb, 2013). Based on this definition, university professors’ are not very interdependent. Even though they are a part of a college and/or a university, they are independent in most aspects related to their teaching. Professors work independently to determine the content of their classes, to create the materials for those classes, and to deliver the material.

In his seminal article, Wood (1986) identified three components of task complexity: component, coordinative, and dynamic. Component complexity deals with the number of independent acts that must be performed to complete a task. Coordinative complexity is the types of relationships between what is required to do the task and the outcome of the task. The dynamic component describes the degree to which an environment changes and the responses required to those changes. Within this paradigm, one can infer teaching is a complex task: innumerable activities must be performed to prepare and execute a plan for imparting knowledge in such a way that learning takes place; the curriculum process requires high levels of coordination (NOTE: we will argue later that implementation of the curriculum is hindered by the lack of coordination); and not only does subject matter change for any given topic, but so do the needs of the learners within a classroom.

Complex tasks, according to Drafke (2009), require greater interdependence and are more effectively executed through groups and teams, a format that provides an opportunity for individuals to build upon each other’s skills, experience, and perspectives, to achieve better results. Increasingly organizations with complex environments adopt the team format– universities typically have not.

A school’s curriculum should be coherent and include complementary elements that fit with each other. Greater collaboration in designing different classes should result in greater coordination, less redundancy and gaps in the overall curriculum, and more consistency in terms of the quality of the classes (Hurwitz, et. al., 2014). Interdependence among teaching faculty promotes collaboration that is currently missing (Hurwitz, et. al., 2014), mostly due to the structure of colleges and the processes they employ (D’Andrea & Gosling, 2005).

Issue 2: The Focus on Teaching Rather Than on Learning

As scholars have noted, most higher education institutions embrace a culture which emphasized accumulating credit hours and attaining good GPAs (Arum & Roksa, 2011). This culture has created a separation between faculty, who focus on teaching and research, and students who focus on extra-curricular activities rather than on academic pursuit (Arum & Roksa, 2011). A major outcome of this emphasis has been that student graduate from college without learning important skills such as critical thinking and logical writing, which are necessary for professional success in today’s environment (Arum & Roksa, 2011).

The core mission of education should not simply be to ensure that students are taught a certain amount of classes which include important information. Rather, it should focus on ensuring that they learn important overarching skills—a learning focus rather than a teaching focus. However, higher education institutions’ traditions seem to hinder changes to the organizational structure or the evaluation system in ways that would promote learning (D’Andrea & Gosling, 2005).

The classroom environment, just as it was 200 years ago, remains one teacher operating independently. Most faculty evaluation systems attempt to evaluate “teaching” rather than “learning,” which becomes the partial basis for merit increases, promotion, and tenure decisions (Markwell, 2003). For example, Seldin (1997) itemizes 13 characteristics of a teacher that should be evaluated. None have any reference to learning. Wieman (2015) describes five criteria by which teaching effectiveness should be measured: validity, meaningful comparisons, fairness, practicality, and improvement. One would hope validity would be a measure of student outcome; but unfortunately, Weiman is referring to comparative teaching evaluation scores among faculty, not student outcomes. Similar practices exists across nations (See Chen and Yeager, 2011 for practices in China and Centre for Development and Enterprise, 2015 for a number of other countries).

The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) Assurance of Learning Standard is an attempt by the largest accrediting agency of business programs to address learning. That standard may measure student learning over a small number of pre-identified topics, but does little to address students’ success as they progress through the system; nor does the standard in assigning responsibility for that success.

Resources are estimated and allocated based primarily on teaching philosophies and strategies rather than on learning needs of students. For example, curricula tend to remain stable whether or not students attain their learning objectives or not (Centre for Development and Enterprise, 2015). The curriculum as a whole stays the same, and so does the content of the individual course syllabi. One does not observe alterations in curriculum in a timely basis when it becomes apparent students have not met mastery expectations for a course or course sequence.

Furthermore, one does not typically see curriculum change driven by changing trends in the environment related to learning needs. For example, colleges or departments typically do not respond quickly to student needs for a specific skill set, whether it be technological or a “soft” skill dictated by the market of potential employers (Lohman, 2003). The curriculum and course syllabi will come across as decades out of date. The reason is simple: the curriculum gets set by the department, and the course syllabi are developed by individual faculty, and there is nothing that would force the inhabitants of the department to go with the times. The stimulus and emphasis is just not structurally there (Schneider, 2013).

The focus on teaching not only distracts universities from their main objective of helping students learn, but also creates a standardized, linear educational process, because the system is not attentive to the needs of individual students or groups with common interests. Rather, universities should use a dynamic model (see figure 1) in which faculty and student have ongoing dialogue and the system can adapt to the needs of smaller groups (cohorts) of students.

The focus on teaching rather than on learning also has a negative impact on student and faculty motivation. In a nutshell, we suggest current motivational forces direct faculty to focus their attention to teaching, and focus students’ attention on achieving standard extrinsic outcomes in the form of grades.

Motivation refers to the forces that drive human behavior (Lawler, Hackman, & Kauffman, 1973; Robbins, 1993; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Therefore, any discussion about the performance of faculty and students should include an analysis of motivational factors.

The literature in social psychology distinguishes between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. While the first refers to external forces guiding employee behavior (e.g. a salary, a promotion, etc.), the later refers to internal sources driving such behavior, such as enjoyment, curiosity, and self-fulfillment (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Research indicates that intrinsic motivation is more useful for increased effort in non-trivial and mechanical tasks, because individuals are more willing to persist in challenging tasks when they experience feelings such as enjoyment, fulfillment, and intellectual stimulation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). An example: for a simple technical task like attaching a button to a coat, extra pay (extrinsic motivator) normally leads to improved performance. However, for a more cognitively complex task, such as designing and teaching a college class, or learning complex concepts, intrinsic motivators are significantly, and sometimes the only valid motivators. Designing curriculum and teaching are not simple mechanical tasks and therefore those performing them should respond better when intrinsically motivated.

The traditional university structure focuses on extrinsic motivators, which include salaries and promotions and for which Universities have clear expectations. Those expectations primarily include proficiency in teaching, as measured by student evaluations; research, as measured by quantity and quality of publications; and service, as measured by participation in the governance of the department, college, and university. Of these extrinsic evaluation criteria, teaching is the obvious category for motivating change in the classroom.

The lack of alignment between university reward systems and the core activity of academics is the biggest challenge facing government and universities (Chen & Yeager, 2011). Current evaluation models and incentives for faculty teaching are not motivating enough because they are extrinsic and those extrinsic motivators largely ignore the ultimate purpose of teaching, which is student learning. Rather, as mentioned earlier, faculty teaching is evaluated based on professor behaviors and attributes such as professor preparedness for class, perceived knowledge of the material, style of teaching, etc. These evaluation criteria do not motivate faculty to focus on student learning but rather on the teaching criteria (such as those listed by Seldin, 1997), found in the assessment instrument. Therefore, we advocate a new organizational structure that would intrinsically motivate faculty and students and emphasize student learning. The following section will elaborate on the importance of this new organizational structure.

For students, the primary extrinsic motivational factor is a course grade. However, as the literature cited points out, extrinsic motivation is a poor behavioral guidance for complex tasks such as learning. Research indicates that students with intrinsic learning goals, rather than extrinsic grade attainment goals, combined with effective feedback, result in increased learning (Markwell, 2003). The traditional class structure of a college and curriculum does little to spur intrinsic motivation and the resulting behavioral changes.

DuFour’s Questions

As a first important step for addressing the problems mentioned above about the focus on teaching, we suggest using DuFour’s (2005) four questions that educational institutions should answer to meet their core missions. These questions focus on learning rather than on teaching and can serve both as a benchmark for assessing the current state of affairs, and as a guide for restructuring the higher education system. DuFour’s questions are:

- What is it we want the student to learn?

The decision on what students will learn is ultimately left to the discretion of each professor. The college, through a burdensome, hierarchical process, decides which classes are required based on a broad description. Individual professors then determine the details of what students are taught, based on the professors’ understanding of their field of expertise.

- How will we know when each student has mastered the essential learning?

This issue focuses on assessment and the use of the information gathered (feedback). Universities engage in several types of assessments. One type of assessment is student evaluations of faculty teaching. At the conclusion of each course, the university requests students to complete teaching (not learning) evaluations which focus on professors’ behaviors and traits and are quite heavily impacted by students’ personal preferences (Gross, Lakey, Edinger, Orehek, & Heffron, 2009). Those evaluations, which do not, by design, measure student learning, then become a major factor in professors’ formal performance evaluations. Assessments will be more useful to students, faculty, and the organization if they are founded on how much students learn.

A second type of assessment is conducted by professors for grading purposes. These assessments, purportedly of learning, are internal, in the sense they are used only by professors for their own classes. These assessments rarely become an input to larger learning objectives of the organization, and are rarely, if ever, used to adjust curriculum.

A third type of assessment is relatively new for universities and is determined by the AACSB. Even though this assessment is driven by learning objectives, those objectives are not course specific (but rather program specific), they are administered sporadically, and do not provide the feedback necessary for making improvements in learning.

- How will we respond when a student experiences initial difficulty in learning?

Many assessments of student learning are not timely, because it is typically done at the end of the semester; consequently, students do not benefit from the assessment. To the extent anyone benefits from assessment it is the instructor, who receives feedback. Because the current assessment focuses on teaching, neither students nor professors have informative feedback about what students learned relative to their learning goals. DuFour’s principles would support a timely and systematic intervention as a result of leaning assessment. Specifically, an ideal response to suboptimal learning performance would involve a timely intervention unique to each student’s needs, which is not possible in the current system.

- How will we deepen the learning for students who have already mastered essential skills and knowledge?

Currently, not much, if anything, is done in response to positive assessment outcomes indicating students and/or faculty are meeting their goals (Centre for Development and Enterprise, 2015). Rarely are additional learning opportunities made available to high achieving students. Rarely are exceptional students challenged to go even further. And rarely are additional resources made available to the top 5% of students, in direct contrast to the myriad of programs instituted to support struggling students. In the spirit of continuous improvement, feedback should be used to improve processes and outcomes not only when goals are not met, but also when they are achieved.

A New Organizational Structure for Higher Education

This paper proposes a different organizational structure for colleges in higher education that promotes focusing on learning rather than on teaching and greater interdependence among faculty. Our proposed structure is based upon three “non-traditional” approaches to teaching: Student Cohorts, Team Teaching, and Learning Communities. In the next section we will discuss each of those concepts and explain how they address the issues we have identified earlier (lack of interdependence, focus on teaching). Then, we will discuss our proposed concept of a learning cohort – a learning team of students and faculty, which lies at the heart of our proposed new structure. Finally, we will address the obstacles colleges of in higher education might face in trying to implement such a plan.

Student Cohorts

Student Cohorts are groups of students who work together on a common education program, collaborating throughout the process, and developing a sense of community (Sapon-Shevin & Chandler-Olcott, 2001). The most significant advantages of student cohorts are: enabling students to learn in an atmosphere of cooperation and trust (Burnaford & Hobson, 1995), improving retention rates (Patterson-Lorenzetti, 2003), and enhancing learning by placing learning first (Fenning, 2004).

Student cohorts have been successfully used in a variety of disciplines at a widely diverse number of colleges. At the University of Virginia, the renowned McIntire School uses it in both their MBA program the Management of Information Technology. “I gained so much knowledge both from the faculty and my fellow students, and that knowledge continues to benefit me. I’ve been able to develop business opportunities in ways that I didn’t even know were possible. (Rudin, 2015).” The University of Utah uses student cohort learning groups in their general education program and their Honors College (University of Utah, 2016). Education programs seem to be natural places for student cohort programs such as the online program at Texas Tech where they begin a new cohort group each semester to follow a prescribed curriculum together (Texas Tech, 2016).

Despite the wide use and the vast amount of literature describing benefits of cohort teaching, research suggests that it is not a panacea. Some researchers report rancor and ill will among members of the cohort (Knorr, 2012), and cliquishness (Sapon-Shevin & Chandler-Olcott, 2001). None of these things, however, if corrected by additional faculty training should prevent cohorts from developing the benefits reported by others (Agnew, et. al., 2008). Mather and Hanley (1999) offer a great insight to the controversy. They state that the advantages of cohorts are dependent on the structure of the program. And the crucial structural element is adding a cohort of teachers to simultaneously collaborate in the learning process of their unique student cohort. We couldn’t agree more, and now turn our attention to the idea of a cohort of teachers.

Team Teaching

Team teaching, also referred to as collaborative teaching or co-teaching, typically involves two or more teachers collaboratively sharing instruction responsibilities in one classroom, in order to achieve what either could not have accomplished alone. Esterbv-Smith and Olive (1984) described five types of collaborative teaching: a) Star – one teacher holds major responsibility for the course, collaborators function as guest lecturers; (b) Hierarchical – one senior teacher responsible for most of class, junior instructors assist in discussions; (c) Specialist – collective designing of curriculum by team members, each one taking major role according to special knowledge, all assisting in discussions; (d) Generalist – collective designing of curriculum but teaching divided by practical considerations rather than specialty; and (e) Interactive – collective designing of curriculum, teaching highly flexible according to need at time of teaching rather than in advance.

Team teaching frequently has a positive impact on students. For example, students have reported that team teaching holds their attention and to makes the material more “accessible” (Gillespi & Israetel, 2008). Benjamin (2000) found improved student learning outcomes from reflective and collaborative teaching. Johnson, Johnson, and Smith (2000) reported higher achievement levels, greater retention rates, and improved interpersonal skills for students in collaboratively taught classes. Students who are involved in classes using collaborative teaching techniques improve their social and communication skills and develop skills of analysis and judgment (Harris & Watson, 1997).

Teachers also benefit from team-teaching approaches. Co-teaching creates a dynamic learning environment, facilitates interactive learning, provides a way of modeling thinking across disciplines, and inspires new research ideas (Leavitt, 2006). New professors can gain valuable teaching experience under the guidance of a senior faculty member (Coffland, Hannemann, & Potter, 1974), and older faculty can learn new teaching methods and ideas from their colleagues (Davis, 1995). Consistent with these findings, other researchers report that collaboration on teaching efforts and discussing common students reduces the isolation that many academics experience (Davis, 1995; Hinton & Downing, 1998; Robinson & Schaible, 1995). These authors have found that by changing the job structure of faculty, they become more closely aligned with the educational mission of the institution and feel a greater responsibility for it—an intrinsic motivation enhancement. This will become an important foundation for our suggested reorganizational structure.

Professional Learning Communities

The final concept that serves as a foundation for our reorganization is Professional Learning Communities (PLC). Professional learning communities have become fairly commonplace in education, especially in secondary schools. A learning community in education is composed of teachers and administrators who seek to enhance their teaching skills by continuous learning, and sharing their acquired knowledge with each other (Hord, 1998). The primary impetus for learning communities is to provide development opportunities for faculty to engender a greater sense of ownership in the strategies of educational improvement that is focused on learning (Feger & Arruda, 2008).

A learning organization encourages active participation of employees in creating a shared vision and culture to support collaboration so that they can work together more effectively in identifying and solving problems (Senge’s, 1990). Astuto, et. al. (1994) translated that idea from business to education. She and her colleagues examined the effects of shifting how teachers plan and carryout instruction from a model of isolation to one in which organized collaboration occurred. Admittedly, rigorous research of PLCs is limited (Feger & Arruda, 2008). Vescio, Ross, and Adams (2008) examine the effectiveness of PLCs through a review of 11 studies focused on PLCs. Although they observe that ‘few studies move beyond self-reports of positive impact’. Research done on the effectiveness of Learning Communities indicates that : 1) Teaching practices change through improved collaboration and more focus on student learning than prior to the implementation of learning communities, and 2) achievement scores improved (Vescio, et. al., 2008); and 3) students are more engaged and enjoy their college experience more (Zhao & Kuh, 2004).

In higher education, professional learning communities have been extended to “faculty learning communities,” which transform higher education institutions into learning organizations (Cox, 2004). At Miami University, members of a faculty learning community worked together for a year learning how to enhance teaching and building community. Individuals tried out innovations, participated in seminars and retreats, and presented results of projects they worked on during the year.

Cox (2004) identified two types of faculty learning communities: cohort-based and topic-based. A cohort-based community addresses the teaching, learning, and development of faculty that has been isolated, fragmented, neglected, or stressed by the academe. A topic-based community addresses a special campus teaching and learning need, issue or opportunity. The benefits of faculty learning communities are found in both faculty and student groups. This research reports that faculty reported less stress, higher tenure rates, increased awareness of different teaching styles, and were more frequent contributors to the life of the academe through service on committees, chairmanships, and mentors (Cox, 2004). Students benefited by increased ability to apply principles and generalizations to new problems, increased ability to synthesize and integrate information into ideas, greater interest in topics, and better performance on papers and exams. Missing in a faculty learning community, however, is the sense of responsibility for students’ complete educational experience.

In summary, student cohort groups have the advantages of creating a learning atmosphere of trust and cooperation (Burnaford & Hobson, 1995) and enhanced learning (Fenning, 2004). Cohort teaching improves student learning (Benjamin, 2000), and promotes higher achievement levels (Johnson, Johnson, & Smith, 2000), while faculty rid themselves of the isolation feeling and the unsupported independence (Davis, 1995; Hinton & Downing, 1998; Robinson & Schaible, 1995). Faculty learning communities also contribute to a stronger sense of community and commitment to organizational goals and changes (Cox, 2004), while creating an environment where learning is given a higher priority (Vescio, et. al., 2008). Each of these innovations can make marginal improvements to a college, but without the organizational structure to support and encourage them, they become isolated pockets with only their champions participating.

These proven approaches to learning have become the exception rather than the norm, because of universities’ traditional organizational structure. Departmental structures, so prevalent in most colleges and universities, isolate disciplines, making it impossible to appropriately evaluate learning as a whole and further make it impossible to correct problems because they are not being detected until students graduate and when employers are challenged with the issue. The isolation that faculty encounter discourages them from feeling a sense of responsibility for the overall educational experience and gives them limited ways of placing the context of their disciplines with the overall scheme of higher education. Reorganization can overcome these deficiencies. We now turn to a discussion on the main tenet of our proposed new structure, which will draw on the strengths of each of the “non-traditional” learning modes and combine them through a new organizational structure – Learning Cohorts.

A Learning Cohort

Our goal in proposing a different organizational structure for a college of in higher education is to move toward a more holistic approach to education where learning is the focus of both students and faculty members. Scholars have noted an integrative and applied learning experience is one that can prepare students for today’s ever changing environment (Schneider, 2013).

We propose that colleges be organized into “learning cohorts.” We define a learning cohort as, “A cross-functional team of faculty and a group of students who stay together throughout the learning process.” Learning cohorts are bound by a theme/track/concentration unique to the cohort. These themes are mission driven and cross-functional—a college will likely have several concurrent themes. For example, a college of business may have committed itself to three primary areas of business education for which it would like to be the college of choice for students and employers. Suppose the three areas were Global, Innovation, and Analytics. Faculty and students with interests in each of these areas would be assigned to the learning cohorts. Members in the new learning cohort have a shared vision based on the cohort’s theme. In accordance with AACSB guidelines, these themes should be mission driven and supported by resources, as well as cross-functional. Table 1 is a visual representation of this structure.

Table 1. Learning Cohort Organizational Structure within a College of Business

| Management | Marketing | Finance | Accounting | |

| (Global Track) | Cohort 1

|

|||

| (Innovation Track) | Cohort 2

|

|||

| (Analytics Track) | Cohort 3

|

|

Responsibilities and Functioning of the Learning Cohort

Faculty members within the cohort are responsible for the educational experiences of that cohort of students from the time they enter the college of business until the time they graduate. Their first task would be the creation of learning objectives for cohort students. From those learning objectives they would design the curriculum, within the guidelines of the college and accreditation requirements, but with emphasis on the theme of the cohort. Since the cohort has a central theme, the curriculum may have non-traditional learning experiences such as extended learning projects, directed internships, or collaboratively-taught, discipline-integrated courses.

The faculty cohort is responsible for assessing learning. Assessment at most universities is centered on the opinions of students about the teaching prowess of the faculty member with little or no regard for what or how much a student has learned. In a learning cohort, learning becomes the responsibility of all members of the cohort and its assessment will be of paramount importance to meet the learning objectives of the learning cohort. Since the cohort of faculty members has all students in common, they should be able to easily identify those students who are struggling and those who are excelling. Because the curriculum is more flexible, faculty can design learning experiences for each of these groups.

How the learning cohort structure improves processes and learning outcomes

This paper cited two issues with respect to higher educations’ dominate organizational structure – lack of interdependence and a focus on teaching rather than on learning. We will now demonstrate how the learning cohort structure addresses each of these issues.

- Lack of interdependence in the core structure of a professor’s job. In education, the increasing departmentalization and fragmentation of the curriculum represent a growing threat to the quality of the undergraduate experience (Rhodes, 2006). The learning cohort structure changes the “lonely profession” into a team environment. The team format is better suited to handle the complexities and uncertainties of today’s rapidly changing environment (Drafke, 2009; Wood, 1986). Faculty no longer work as lone imparters of knowledge, but become part of a team responsible for establishing comprehensive objectives for the learning cohort; creating learning experiences that fit the needs of the cohort, accomplishing the learning objectives, building on the learning students have acquired in preceding courses; and establishing learning assessments that measure topic mastery which can lead to adjustments in the learning process. Faculty become a part of interdependent teams, relying on one another for topic coverage and as coaches to identify student learning issues or enhancements.

- A focus on teaching rather than learning. Faculty evaluations by students are mitigated and replaced with learning assessments. Faculty cohorts will establish what is to be mastered by the students in the cohort, not only for each course, but also across the curriculum, and create assessment approaches, which allow students to demonstrate mastery of a topic and the ability to apply their knowledge. Cited literature clearly shows the benefits of grouping students into cohorts and faculty into teaching teams. What has been lacking is an organizational structure, which places a sense of ownership, and by extension, a motivation to focus on the learning that takes place as opposed to the teaching that is done. Change is conducive to improved quality teaching and learning only to the extent that an appropriate internal organizational support is in place (Lohmann, 2003). Because faculty members are working together with common students under the umbrella of a common interest, everyone can adjust the learning experience, as would most benefit the learning group. Changing the job structure motivates faculty indifferent ways (Davis, 1995) which in turn changes their professional behaviors (Robinson & Schaible, 1995), allowing assessment efforts to be aligned more closely with the primary mission of higher education— student learning. This aligns closely with research recommendations to tie assessment efforts more closely to faculty priorities for student learning across the curriculum (Schneider, 2013).

- Based on research in the field of motivation, we also suggest the format of learning cohorts will boost professors’ motivation to teach. According to the job characteristics model (Hackman & Oldham, 1976), a job should include several characteristics in order to enhance its holder’s motivation. Those characteristics are: variety, identity, significance, autonomy, and feedback. Jobs that have variety, include various different skills and actions, and are typically not as mundane as those that have low variety. Jobs that have identity enable completing a task at its entirety, with a visible outcome. Jobs that are more significant than others have a greater impact on others’ or on society as a whole. Jobs that have autonomy grant greater leeway and discretion to employees. Finally, jobs that have an element of feedback enable employees to get information about how effective they are, as they work toward completing their tasks.

Individuals whose jobs include variety, identity, and significance, perceive their jobs as more meaningful. Individuals whose jobs have high autonomy, perceive they have a higher degree of responsibility for the outcomes of their performance; and those whose jobs include feedback have more knowledge of the result of their work. Hackman and Oldham’s (1976) model further postulates that perceived meaningfulness, responsibility, and knowledge of one’s outcomes enhances job satisfaction and overall motivation.

The Learning Cohort structure improves faculty motivation by:

- Improving identity and providing the faculty member with a better perspective on how their teaching and coursework fits into the learning paradigm;

- Enhancing job significance through closer awareness of their impact on students’ educational lives and future professional lives; and finally

- Greater feedback on the most important aspect of teaching—learning.

Implementation Issues

Organizations always face challenges when implementing new ideas, especially if they involve changing cultural and structural elements that have been in place for many years. This section anticipates several salient hurdles that must be overcome for successful implementation.

Faculty Resistance due to Established Organizational Roles and Cultures

Perhaps the greatest challenge to creating a new organizational culture and structure within a college is the entrenched nature of the existing structure and culture. All faculty have gone through a rite of passage in both their preparation for the professoriate and their quest for tenure. The political nature of that system perpetuates the image of what is necessary to be successful, and generally that does not include attempts to change what has been long established.

Faculty who act as change agents within institutions often remain isolated and initiatives designed to raise the status of teaching remain vulnerable (Hannan & Silver, 2000). Furthermore, small groups of self-selected reformers apparently seldom influence their peers (Elmore, 1995). This suggest that unless the strategies to improve teaching and learning are accepted by the majority of faculty within the college structure, individual innovators will continue to remain peripheral to the main culture of a university. Change must be a part of a larger unit than an individual.

However, change depends on the ability and motivation of the change agent (Stoll, Bolam, McMahon, Wallace, & Thomas, 2006). Faculty, because they have not consistently worked in cross-disciplinary fields or worked closely with faculty from other disciplines, may feel frustrated and unprepared to work together.

In today’s student demand-driven environment, financial considerations will also impact colleges’ culture in a way that would be a hurdle to our proposed changes. Over the next decade, many new faculty will be needed, both to replace the large numbers of expected retirements and to teach the growing numbers of students. Both public and private institutions may hire an increasing proportion of faculty who are ineligible for tenure, generally at lower salaries than tenure-track faculty. Growing use of temporary faculty presents both advantages and problems. On the one hand, it increases institutions’ ability to respond to changing student demand and reduces institutional costs. On the other hand, it creates a two-tier academic labor force, one in which tenure-track faculty may not be eager to suggest or try new things and non-tenure track faculty have no ability or political standing to do so. This will make it difficult to enable the collaboration among faculty as we discussed above.

There can also be tensions between institution leaders seeking to change the culture of the institution through centralized steering and the collegial culture that reflects the discipline-specific features of academia. If connections have not already been built between the two approaches, then these tensions will slow the progress that can be made on fostering quality teaching. Indeed, when strategies are implemented from the center in a top-down approach, with little or no engagement from departments, faculty within departments tend to ignore them (Gibb, 2010).

Self-selection by students into cohort groups

Under the traditional model of major selection and advising, students often do not select a major until they are juniors and advising until that time is frequently done by a centralized advising staff. In a cohort learning community approach, students need to affiliate with a themed cohort much earlier to take advantage of the learning cohesion promoted by the approach and to allow faculty cohorts to appropriately plan for the unique demands each cohort will have.

Learning community entrance and exit flexibility

It is easy to change majors; not so easy to change cohorts. Allowing easy entrance and exit from themed learning communities may lose a portion of the binding cohesion created. This problem may be compounded by the maturity of youthful minds in that they often don’t know exactly what they want to do or study and may change their minds several times. Policies for entering and changing cohort groups will need to be well considered.

Identifying cohort themes

Themed areas have to be designed broadly enough to capture interdisciplinary aspects and faculty interest across traditional department lines. Mission driven themes certainly will be the most successful, assuming the themes have been selected based on faculty expertise, resources, and demands of the markets that colleges serve. Themes must be appealing enough to students that they will be willing to commit to and remain in throughout the curriculum.

Curriculum, Learning Assessment and Reporting Processes

Curriculum and assessment are traditionally discipline based. This new structure is more synonymous with the matrix approach to organizational structure. Curriculum might have to be approved by two bosses, both the department curriculum committees and the cross-functional theme team. While the process in higher education often slows changes in curriculum and the lag effect from prior catalog years makes all changes essentially ineffective for several years, it is something that could be tackled with the right tenacity and planning within the curriculum approval processes. Additionally, for state-funded institutions, programs are often continued based on enrollments by disciplines, not themes. Learning communities don’t fit nicely into this package, as the students may not have a specific major. Finally, assessment for regional accrediting bodies may ask for discipline specific measures and this doesn’t correspond well with themed cohort learning environments.

Conclusions and Future Research

Reviewing a wide selection of disparate literature yields the following insights to teaching and learning in higher education:

Insight 1: Organizational structure has an impact on how education is pursued and can influence the learning process.

Insight 2: Learning cohorts of faculty and students can enhance the motivation of both groups. Such motivation is manifested by faculty changing their roles from processing students in narrow areas to having responsibility for students’ educational experience.

Insight 3: What is assessed drives what is done.

The goal of this paper is to move to a more holistic approach of education by restructuring higher education around student learning. The theories behind such a transformative approach suggest that the current status quo in higher education may need a drastic overhaul to better develop learning communities, but such a change should promote a shared vision around a common purpose for both students and faculty.

While several implementation issues were briefly touched upon, working through these issues could possibly lead to students who are better equipped handle the realities of shifting resources within turbulent environments. Breaking down faculty silos and replacing them with learning teams of students and faculty brought together around common themes is a key not only to improved learning, but a channel through which colleges may differentiate themselves. Commitment from faculty is important, as it is in all changing environments, and is the glue that creates an intangible competitive advantage that would be hard for others to imitate. While the challenges are not insurmountable, it will require a paradigm shift in learning. Table 2 represents a summative comparison of the old and new paradigms.

Table 2. Comparison of the Factory Model to the Cohort Model

| “Factory” Model | Cohort Model | |

| Goal of Education | Unidirectional – Teaching Centered | Holistic/Collaborative – Learning Centered |

| Structure of Program | “Factory-Like” Silos without a shared vision | Cross-Functional Learning Cohorts with a shared vision |

| Assessment | Focus on Teaching | Focus on Learning |

| Continuous Improvement | By Department | Across Departments |

Empirical research is needed to verify the specific restructuring plans discussed. Such research should enable higher education institutions to compare the viability and costs of such a structural change with its benefits and to make better-informed decisions. For example, empirical evidence is needed for testing the relationship between the suggested organizational change (i.e. cross-functional faculty and student cohorts) and student outcomes (e.g. student motivation and performance). Another area for empirical research is the impact of the suggested change upon faculty motivation. The suggested change should result in higher faculty motivation. Empirical evidence is therefore required to examine whether the increased interdependence and the shift toward assessing learning versus assessing teaching, indeed increases motivation as proposed. We believe the benefits gained in this new approach will outweigh potentials costs and lead to better understanding and assessing student learning in higher education.

References

Agnew, M., Mertzman, T., Longwell-Grice, H., and Saffold, F. (2008). Who’s in, who’s out: Examining race, gender and the cohort community. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 1(1), 20-32. doi:10.1037/1938-8926.1.1.20

Arum, R., and Roksa, J. (2011). Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses. Chicago, IL: Chicago Press.

Astuto, T.A., Clark, D.L., Read, A.M., McGree, K. and Fernandez, L. (1994). Roots of reform: Challenging the assumptions that control education reform. Retrieved February 4, 2013 from, http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=oandd=98415814.

Banta, T.W., Griffin, M., Flateby, T.L., & Kahn, S. (December, 2009). Three promising alternatives for assessing college students’ knowledge and skills [NILOA Occasional Paper No.2]. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment.

Benjamin, J. (2000). The scholarship of teaching in teams: What does it look like in practice? Higher Education Research and Development, 19, 191-204.

Burnaford, G., and Hobson, D. (1995). Beginning with the group: Collaboration as the cornerstone of graduate teacher education. Action in Teacher Education, 17(3), 67-75.

Centre for Development and Enterprise (2015). Teacher Evaluations – Lessons from other countries. Retrieved from http://www.cde.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Teacher-Evaluation-Lessons-from-Other-Countries.pdf

Chen, Q., & Yeager, J. L. (2011). Comparative study of faculty evaluation of teaching practice between Chinese and U.S. institutions of higher education. Frontiers of Education in China, 6(2), 200-226

Coffland, J. A., Hannemann C., and Potter R. L. (1974). Hassles and hopes in college team teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 25, 166-69.

Cox, M. (2004). Introduction to Faculty Learning Communities. New directions for teaching and learning, 97, 5 – 23.

D’Andrea, V. and Gosling, D. (2005). Improving Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: A Whole Institution Approach. Berkshire, England: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

Davis, J. R. (1995). Interdisciplinary courses and team teaching: New arrangements for learning. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press.

Drafke, M.W. (2009). The Human Side of Organizations, 10th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall

DuFour, R. (2005). On Common Ground: The Power of Professional Learning Communities. Bloomington, IN: Solution-tree.

Elmore, R. (1995). Teaching, learning, and school organization: Principles of practice and the regularities of schooling. Educational Administration Quarterly, 31, 355-374.

Esterby-Smith, M. and Olive, N. (1984). Team teaching: making management education more student-centered? Management Learning, 15(3), 221–236.

Ewell, P. (2013). The Lumina Degree Qualifications Profile (DQP): Implications for Assessment. Retrievd from National Institute for Learning Outcomes March 29, 2016, http://www.learningoutcomeassessment.org/documents/DQPop1.pdf

Fenning, K. (2004). Cohort Based Learning: Application to Learning Organizations and Student Academic Success. College Quarterly, 7(1), 1 – 11.

Feger, S., and Arruda, E. (2008). Professional learning communities: Key themes from the literature. Providence, RI: The Education Alliance: Brown University. Retrieved February 4, 2013 from http://www.alliance.brown.edu/pubs/pd/PBS_PLC_Lit_Review.pdf

Gibb, G. (2010). Dimensions of quality. Higher Education Academy. Retrieved April 2, 2016 from: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/dimensions_of_quality.pdf.

Gillespie, D. and Israetel, A. (2008). Benefits of Co-teaching in Relation to Student Learning. 116 Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association. Boston, MA.

Gross, J., Lakey, B., Edinger, K., Orehek, E. and Heffron, D. (2009). Person Perception in the College Classroom: Accounting for Taste in Students’ Evaluations of Teaching Effectiveness. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39, 1609–1638.

Hackman, J. R. and Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16, 250-279.

Hannan, A. and Silver, H. (2000). Innovating in Higher Education: Teaching, Learning and Institutional Cultures. Higher Education, 42(3), 393-394.

Harris, S. A., and Watson K. J. (1997). Small group techniques: Selecting and developing activities based on stages of group development. To Improve the Academy, 16, 399-412.

Hersh, R. H. & Keeling, R. P. (2013). Changing Institutional Culture to Promote Assessment of Higher Learning [Occasional Paper No.17]. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment.

Hinton, S., and Downing J. E. (1998). Team teaching a college core foundations course: Instructors’ and students’ assessments. Richmond, KY: Eastern Kentucky University. ERIC Document No. ED 429469.

Hord, S. (1998). Professional learning communities: What are they and why are they important? Issues about Change, 6(1), 1 – 9.

Huber, M. T., & Hutchings, P. (2004). Integrative learning: Mapping the terrain. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Hurwitz, D., Swake J., Brown, S., Young, R., Heaslip, K., Bernhardt, K., and Turochy, R. (2014). Influence of Collaborative Curriculum Design on Educational Beliefs, Communities of Practitioners, and Classroom Practice in Transportation Engineering Education. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education & Practice, 40(3), 04013020-1 – 04013020-12.

Hutchings, P. (2010). Opening doors to faculty involvement in assessment [NILOA Occasional Paper No.4]. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., and Smith. K. A. (2000). Constructive controversy. Change, 32, 29-37.

Kim, E., Bhave, D. P. and Glomb, T. M. (2013). Emotion Regulation in Workgroups: The Roles of Demographic Diversity and Relational Work Context. Personnel Psychology, 66, 613–644.

Knorr, R. (2012). Pre-Service Teacher Cohorts: Characteristics and Issues: A Review of the Literature. SRATE Journal, 21(1), 18 – 23.

Lawler, E. E., Hackman, J. R., and Kauffman, S. (1973). Effects of job redesign: A field experiment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 3, 49-62.

Leavitt, M. (2006). Team teaching: Benefits and challenges. Speaking of Teaching,16(1), 1 – 4.

Lohmann, S. (2003). Herding Cats, Moving Cemeteries, and Hauling Academic Trunks: Why Change Comes Hard to the University. In W. Tierney, & L. Serra-Hagedorn (Eds.), From Research to Policy to Practice to Research (pp. 35-51). Center for Higher Education Policy: University of Southern California.

Markwell, D. (2003). Improving teaching and learning in universities. B – Hert News, 18. Retrieved from: http://www.bhert.com/publications/newsletter/B-HERTNEWS18.pdf

Mather, D. and Hanley, B. (1999). Cohort Grouping and Preservice Teacher Education: Effects on Pedagogical Development. Canadian Journal of Education, 24(3), 235-250.

Patterson-Lorenzetti, J. (2003). 5 Factors that Boost Retention in Cohort-Based Programs. Distance Education Report, 7(10), 2-3.

Rhodes, F.H.T. (2006). After 40 Years of Growth and Change, Higher Education Faces New Challenges. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/weekly/v53/i14/14a01801.htm

Robbins, S.P. (1993). Organizational Behavior, 6th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Robinson, B., and Schaible, R. M. (1995). Collaborative teaching: Reaping the benefits. College Teaching, 43, 57-59.

Rudin, A. “Alumni Spotlight” Retrieved from University of Virginia Website March 31, 2015, https://www.commerce.virginia.edu/ms-mit/class-profile.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68-78.

Sapon-Shevin, M. and Chandler-Olcott, K. (2001). Student cohorts: Communities of critique or dysfunctional families? Journal of Teacher Education, 52(5), 350 – 364.

Schneider, C., (2013). The DQP and the Assessment Challenges Ahead. Retrieved from National Institute for Learning Outcomes March 29, 2016, http://www.learningoutcomeassessment.org/documents/DQPop1.pdf

Seldin, P. (1997). Improving college teaching: Learning to use what we know. Paper presented for the international conference on improving college teaching. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Currency Doubleday.

Shavelson, R. J., Schneider, C. G., Shulman, L. S. (2007). A brief history of student learning assessment: How we got where we are and a proposal for where to go next. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of Educational Change, 7(4), 221-258. 14. https://secure2.aacu.org/AACU/PubExcerpts/Briefhis.html.

Texas Tech, (2016). TTU Worldwide eLearning. Retrieved from Texas Tech website, March 31, 2016, http://www.depts.ttu.edu/elearning/masters/educational-leadership/.

University of Utah (2016). Learning Communities and Cohorts. Retrieved from university of Utah website, March 31, 2016, http://studentsuccess.utah.edu/resources/learning-communities-amp-cohorts/.

Vescio, V., Ross, D., and Adams, A. (2008). A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 80-91.

Wieman, C. (2015). A Better Way to Evaluate Undergraduate Teaching. Retrieved from Change Magazine of Higher Education website, March 30, 2016, http://www.changemag.org/Archives/Back%20Issues/2015/January-February%202015/better-way-full.html.

Wood, R. (1986). Task Complexity: Definition of the Construct. Organizational Behavior AND Human Decision Processes, 37, 60-82.

Zhao, C. M., and Kuh, G. D. (2004). Adding Value: Learning Communities and Student Engagement. Research in Higher Education, 45(2), 115-138.

This academic article was accepted for publication in the International HETL Review (IHR) after a double-blind peer review involving three independent members of the IHR Review Board and 1 revision cycle. Accepting editor: Dr Charlynn Miller

Suggested citation:

Blaylock, B., Zarankin, T. & Henderson, B. (2016). Restructuring Colleges in Higher Education around Learning. International HETL Review, Volume 6, Article 6, URL: https://www.hetl.org/restructuring-colleges-in-higher-education-around-learning

Copyright 2016 Bruce Blaylock, Tal Zarankin and Dale A. Henderson

The authors assert their right to be named as the sole authors of this article and to be granted copyright privileges related to the article without infringing on any third party’s rights including copyright. The authors assign to HETL Portal and to educational non-profit institutions a non-exclusive licence to use this article for personal use and in courses of instruction provided that the article is used in full and this copyright statement is reproduced. The authors also grant a non-exclusive licence to HETL Portal to publish this article in full on the World Wide Web (prime sites and mirrors) and in electronic and/or printed form within the HETL Review. Any other usage is prohibited without the express permission of the authors.

Disclaimer

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors, and as such do not necessarily represent the position(s) of other professionals or any institution.