HETL Note:

In this academic article, authors Drs. Erin Schauster, Joonghwa Lee, Patrick Ferrucci, Seoyeon Kim, and Kim Sheehan, present a study (using content analysis as a research strategy) of 143 undergraduate advertising program websites from a cross-section of public and private American universities and colleges. The study suggests that relevant information needed to attract prospective students to an advertising program was either unavailable or difficult for students to locate. The authors make several recommendations that universities and colleges can use to help them in their efforts to attract prospective students to their undergraduate programs.

Author bios:

Erin Schauster (Ph.D. University of Missouri School of Journalism) is an Assistant Professor of Advertising at University of Colorado Boulder. Her research examines industry trends in strategic communication along with the educational and ethical implications, and the relationship between advertising ethics and organizational culture. Schauster’s work is published in multi-disciplinary books and journals including Ethical Issues in Communication Professions: New Agendas in Communication, Persuasion Ethics, American Behavioral Scientist, and Journal of Mass Media Ethics among others.

Erin Schauster (Ph.D. University of Missouri School of Journalism) is an Assistant Professor of Advertising at University of Colorado Boulder. Her research examines industry trends in strategic communication along with the educational and ethical implications, and the relationship between advertising ethics and organizational culture. Schauster’s work is published in multi-disciplinary books and journals including Ethical Issues in Communication Professions: New Agendas in Communication, Persuasion Ethics, American Behavioral Scientist, and Journal of Mass Media Ethics among others.

Joonghwa Lee (Ph.D. University of Missouri-Columbia) is an Assistant Professor in the Communication Program at the University of North Dakota. His research interests lie in interactive and non-traditional advertising as well as consumer behaviors. His research has been recognized in peer-reviewed journals, such as International Journal of Advertising, New Media and Society, Communication Research Reports, and Journal of Interactive Advertising.

Joonghwa Lee (Ph.D. University of Missouri-Columbia) is an Assistant Professor in the Communication Program at the University of North Dakota. His research interests lie in interactive and non-traditional advertising as well as consumer behaviors. His research has been recognized in peer-reviewed journals, such as International Journal of Advertising, New Media and Society, Communication Research Reports, and Journal of Interactive Advertising.

Patrick Ferrucci (Ph.D. University of Missouri School of Journalism) is an assistant professor of journalism in the University of Colorado-Boulder’s College of Media, Communication and Information. His research examines aspects of media sociology, primarily organizational influences, such as technology and economics, on news production processes.

Patrick Ferrucci (Ph.D. University of Missouri School of Journalism) is an assistant professor of journalism in the University of Colorado-Boulder’s College of Media, Communication and Information. His research examines aspects of media sociology, primarily organizational influences, such as technology and economics, on news production processes.

Seoyeon Kim is a PhD student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Seoyeon Kim is a PhD student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Dr. Kim Sheehan is a Professor and Honors Program Coordinator at the University of Oregon. Sheehan received a Ph.D. from the University of Tennessee Knoxville. Sheehan’s research involves culture and new technology, and she has published extensively about social media, online privacy, green advertising, advertising ethics, and Direct-to-Consumer prescription drug advertising. Sheehan is a past President of the American Academy of Advertising.

Dr. Kim Sheehan is a Professor and Honors Program Coordinator at the University of Oregon. Sheehan received a Ph.D. from the University of Tennessee Knoxville. Sheehan’s research involves culture and new technology, and she has published extensively about social media, online privacy, green advertising, advertising ethics, and Direct-to-Consumer prescription drug advertising. Sheehan is a past President of the American Academy of Advertising.

Get With the Ad Program: Website Content Analysis

Erin Schauster, Patrick Ferrucci

University of Colorado Boulder, USA

Joonghwa Lee

University of North Dakota, USA

Seoyeon Kim

University of North Carolina, USA

Kim Sheehan

University of Oregon, USA

Abstract

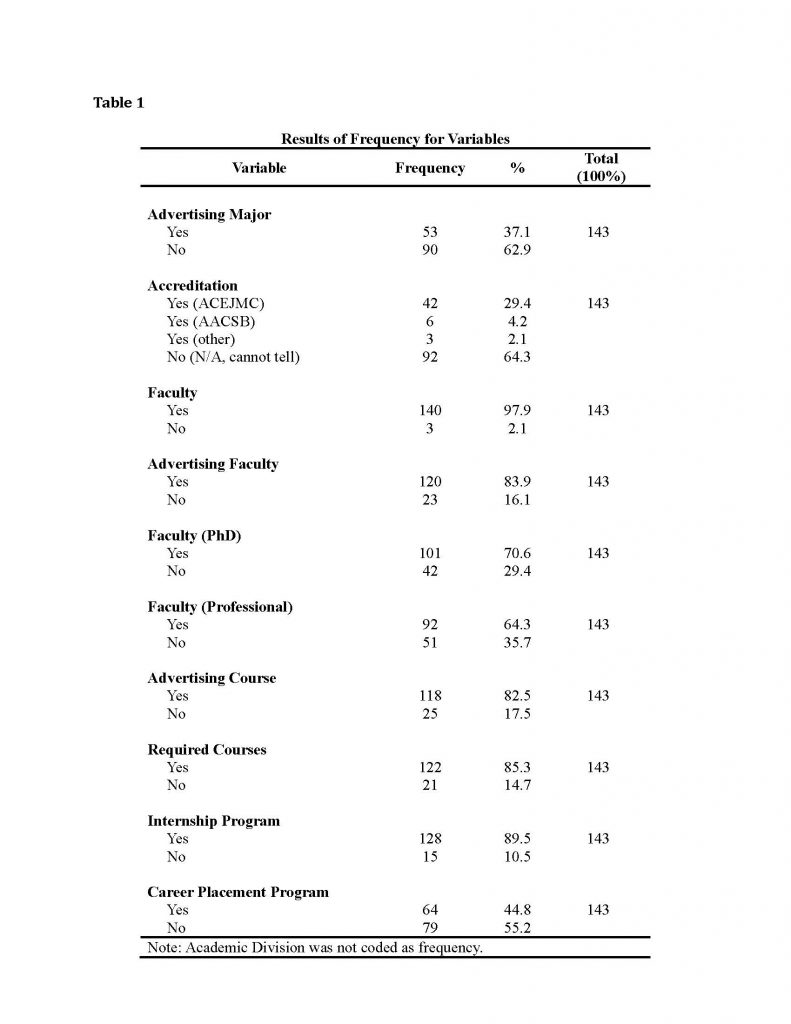

There is an increasing competition to attract students to higher education. This research is one of the first to examine access to undergraduate advertising programs’ website content to identify information that is and is not accessible to prospective students engaged in an online search. A content analysis of 143 undergraduate advertising program websites was conducted. The results indicate the percentages of programs that list relevant program information including advertising programs listed as majors (37.1%) versus non-majors (62.9%), faculty (97.9%), faculty with advertising expertise (83.9%), faculty with Ph.D. (70.6%), faculty with professional experience (64.3%), required courses (85.3%), advertising-specific courses (82.5%), internships (89.5%), and career placement services (49.8%). The authors suggest that information necessary to attract students to an advertising program was, at times, not available or difficult to find. Through the perspective of college selection theory, three recommendations are made for providing usable and clearly identifiable information online: define non-major classifications, prominently display faculty members’ academic and professional achievements, prominently display internship opportunities and career services. These findings and recommendations pave the way for future analyses of online representations of undergraduate programs so that these programs can successfully attract prospective students.

Keywords: content analysis, college selection theory, advertising, undergraduate programs

Introduction

College is about a lot more than educating. Want proof? Just sit in on a faculty meeting. This becomes especially evident to newly appointed tenure-track instructors. Their responsibilities go beyond teaching, scholarship and service discussed in graduate school. Working at a university is also about enrollment, which is becoming increasingly competitive (Maringe, 2006). The reality for newly appointed instructors is that marketing universities and keeping enrollment up can make quite the difference to a department’s budget. Advertising programs are no exception.

There are various elements, including the faculty and curriculum, working together to make an undergraduate advertising program successful. More importantly, without prospective students interested in advertising careers, there would be no enrollment. Prospective students must be able to access information (Bok, 2003) that is thoughtfully developed (Anctil, 2008), and that clearly explains and successfully promotes the program. A marketing strategy is necessary for guiding the development of promotional materials including information available online. A successful strategy should be based upon an understanding of what information influences student decisions (Kotler & Fox, 1995).

Advertising education research enjoys a long life (e.g., Allen, 1960, 1962; Applegate, 2007; Banning & Schweitzer, 2007; Ross, 1965; Rose & Robbs, 2001; Stuhlfaut & Farrell, 2009). However, no study to date has examined how undergraduate advertising programs are represented online to prospective students interested in advertising careers. College selection theory posits that students interested in attending college will spend time researching options and gathering information online (Chapman, 1986). An online presence has become the ultimate source for prospective students (Hartman, 1997). The extent to which undergraduate advertising program websites provide relevant information to prospective students has yet to be examined. Therefore, a content analysis of 143 undergraduate advertising program websites was conducted. Based upon the information available online, as well as what was missing, recommendations are made to improve the online representation of undergraduate advertising education.

Literature Review

The three parents of psychology, business and journalism yielded advertising education (Ross & Richards, 2008). In 1893, the University of Pennsylvania offered advertising as a single course in a journalism program (Applegate, 1997; Ross & Richards, 2008). In the early 1900s, advertising was offered as a subject in marketing programs of business schools (Applegate, 1997). Decades later, in 1965, advertising was more often housed under business and marketing colleges, schools and departments, than under journalism and communication colleges (Ross, 1965). The year 1987 marked the first Ph.D. in advertising, offered at the University of Texas (Ross & Richards, 2008). And by 2007, the placement of advertising programs moved from business and marketing colleges back into journalism and communication colleges (Ross & Richards, 2008).

Advertising Curricula & Faculty

The debate on advertising education needing a general, liberal arts foundation versus an advertising-specific, creative focus is ongoing (e.g., Applegate, 2007; Banning & Schweitzer, 2007; Marquez, 1980 as cited in Applegate, 1997; Robbs, 1996; Russell, 1997; Stuhlfaut & Farrell, 2009). Emphasis tends to lean toward learning basic principles, which a university or liberal arts education provides, versus developing a portfolio, or practical experience, which a trade or portfolio school provides. Lee and Ryan (2005) surveyed creatives and found that 70.6% of respondents received a Bachelors degree in journalism or communication, whereas 37.3% attended a portfolio school. According to these creatives, not all agreed, including those who attended portfolio schools, that attending portfolio school is essential to landing an entry-level creative job. However, most all respondents did agree that being well rounded in education is crucial (Ryan & Lee, 2005). Similarly, in an analysis of online, advertising job postings, the skill and keyword “creativity” appeared in 12.6% of postings, whereas oral, written and organizational skills appeared 49.6%, 42.6% and 42.2% of the time, respectively (Lowry & Xie, 2008).

Neither university programs with a liberal arts foundation nor portfolio schools with a creative focus can prepare students for all real-world advertising assignments (Blakeman & Haley, 2005). This is due, in part, to the demands and changing nature of the industry. Because industry practices change so rapidly, so too must curriculum (Barnes & Lloyd, 2000; Blakeman & Haley, 2005; Blanchard & Christ, 1993). The challenge of keeping up with industry trends calls for flexible and integrated curricula, which acknowledges the potential of limited resources, but still provides attention toward students’ personal and professional development (Duncan, Caywood & Newsom, 1993). In part, coursework that gives attention to professional development prepares students for the job market. However, as graduates come to learn, finding work upon graduation can prove difficult (Becker, 1990).

According to agency executives, desirable job candidates possess practical experience (Gifford & Maggard, 1975), which, for students, is often provided via internships (Banning & Schweitzer, 2007). For creatives working in the industry, 58.8% of those surveyed had completed an internship in advertising or marketing before landing a full-time position (Lee & Ryan, 2005). However, not all schools have the resources or industry connections necessary to implement an internship program. Therefore, some programs embrace a teaching concept that puts advertising students to work on real advertising campaigns. This style of teaching emphasizes the pressures of working on a real account and for a real client (Thayer, 1990). An example would be to assign teams to a real-world client account and require students to develop and give a client presentation (Spiller, Marold, Markovitz & Sandler, 2011).

Practical experience is also an important attribute for faculty. During the 1960s, advertising faculty had an average of five to eleven years of professional experience (Allen, 1960; Ross, 1965), and in 2005, advertising faculty had an average of twelve years professional experience (Ross & Richards, 2008). Faculty members contribute to advertising programs not only through scholarship and pedagogy, but also by applying their professional experiences and insights to projects and other course requirements. Furthermore, educators and practitioners alike have suggested that faculty with industry experience impact students more so than curriculum (Banning & Schweitzer, 2007).

College Selection Theory and Online Presence

Universities must recruit and enroll students to survive in today’s competitive marketplace. In fact, the marketing of higher education is regarded as part of the institution’s educational mission (Anctil, 2008). A higher education marketing strategy should create a tangible identity, be clear in purpose, thoughtfully developed and well maintained (Anctil, 2008). Furthermore, a professionally developed marketing campaign increases the likelihood that a school will stand out in a crowded marketplace (Bok, 2003).

Kotler (1976) proposed a seven-stage model identifying the steps a student takes to choose and register for higher education. During the second stage, information seeking and receiving, prospective students may consider a set of institutions and pursue information through various means. Hossler and Gallagher (1987) condensed Kotler’s model into three stages: 1) predisposition to attend college, 2) search, and 3) selection. The theory of college selection identifies the second stage of both models as the search stage, or search behavior (Chapman, 1986). According to the theory, students search for the attributes that characterize colleges such as cost to attend, academic quality, career opportunities upon graduation, and other related considerations of interest.

When information is clearly presented online, an institution and their respective programs have the opportunity to attract prospective students. Kotler & Kotler (2013) suggest that a consumer’s brand preference is influenced by easily available online information. Relative to post-secondary education, and under the assumptions of choice or selection theory, Plank & Jordan (2001) found that available and increased amounts of information was positively and significantly associated with enrollment in 4-year versus 2-year post-secondary institutions as well as versus no enrollment. In the selection process, Lovelock (2001) affords attention to the pre-purchase stage, which embraces a consumer’s 1) awareness of a problem or need, 2) search for information and 3) evaluation of information gathered. Higher education institutions can influence a student’s awareness of a need, information gathering and subsequent decision-making to attend college by the way they provide information about their campuses and programs available (Christiansen et al., 2003).

Usable information that influences a consumer’s decision should be a part of a well-developed marketing strategy (Kotler & Fox, 1995). Previously, students gathered information on higher education from their guidance counselor, through pamphlets and college catalogues. Today, institutions deliver the same information online. Before the turn of the century, Hartman (1997) argued that the Internet was quickly becoming the ultimate source for students to gather information on higher education. The profile of today’s student population, Generation M, must be considered. Generation M has grown up with the Internet. They surf the net in school computer labs, on their laptops and mobile devices. Generation M have been known to spend an average of one and a half hours per day using the computer outside of school (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010). According to the Foundation, home Internet access increased for this generation from 74% in 2005 to 84% in 2010, high-speed Internet access increased from 31% to 59%, and owning laptops increased from 12% to 29%.

Now, more than ever, it is important that institutions reach this generation of students with accessible websites and preferred web content. In a study of college-bound students, 66% stated that websites were the most important source in the university search process (Clayton, 2003). For university information in general, students expect to see information on admission criteria and majors listed (Anderson & Reid, 1999), as well as information about jobs and internships (Mechitov, Moshkovich, Underwood, & Taylor, 2004). Students consistently complain about hard-to-find information on university websites (Anderson & Reid, 1999; Mechitov et al., 2004).

Therefore, to examine advertising programs as they are represented online to prospective students, we asked

RQ 1: How are undergraduate advertising programs presented online to potential students?

RQ 1a: Is advertising listed as a degree?

RQ 1b: What academic divisions are advertising programs listed under?

RQ 1c: Are advertising programs labeled as accredited programs?

RQ 2: What online information represents the advertising program and attracts prospective students to the program?

RQ 2a: Are faculty members presented and, if so, by both professional and academic experiences?

RQ 2b: Are advertising specific courses listed?

RQ 2c: Are course requirements listed?

RQ 2d: Are internships listed?

RQ 2e: Are career services listed?

Method

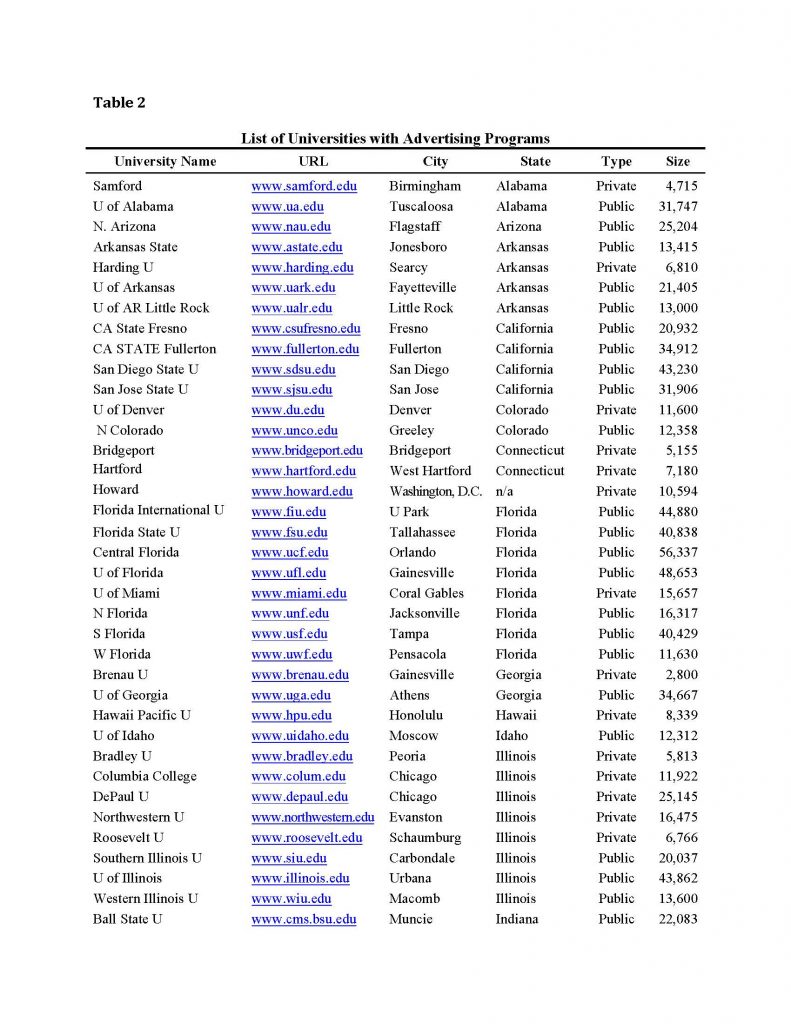

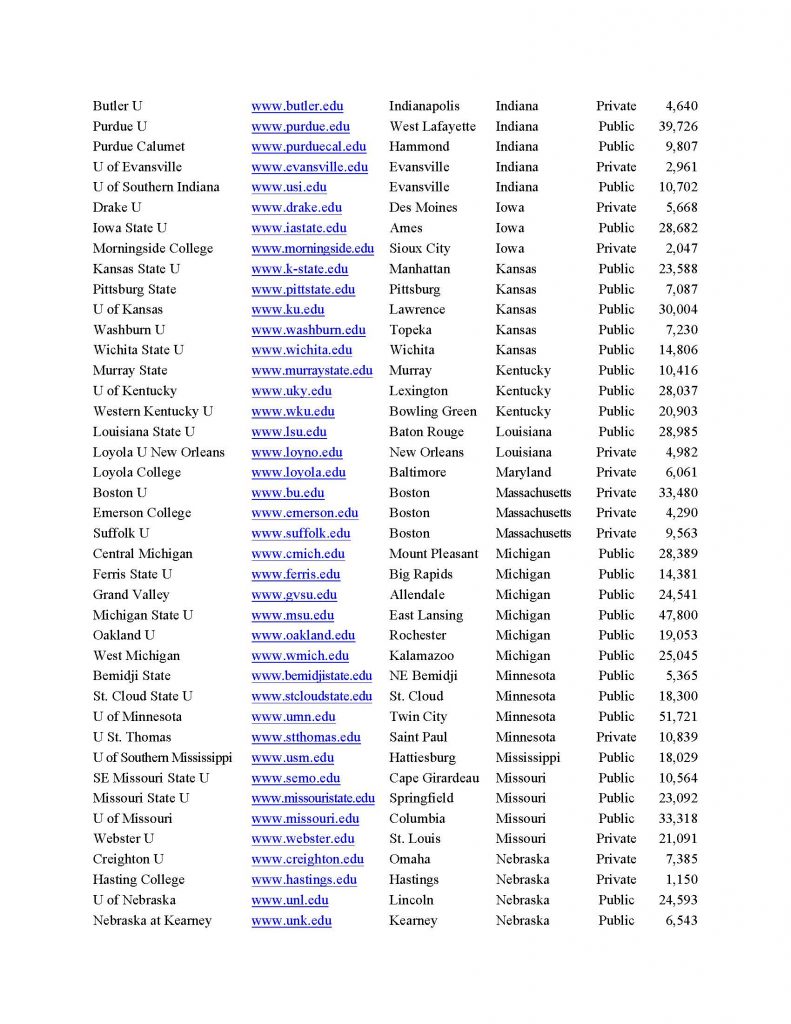

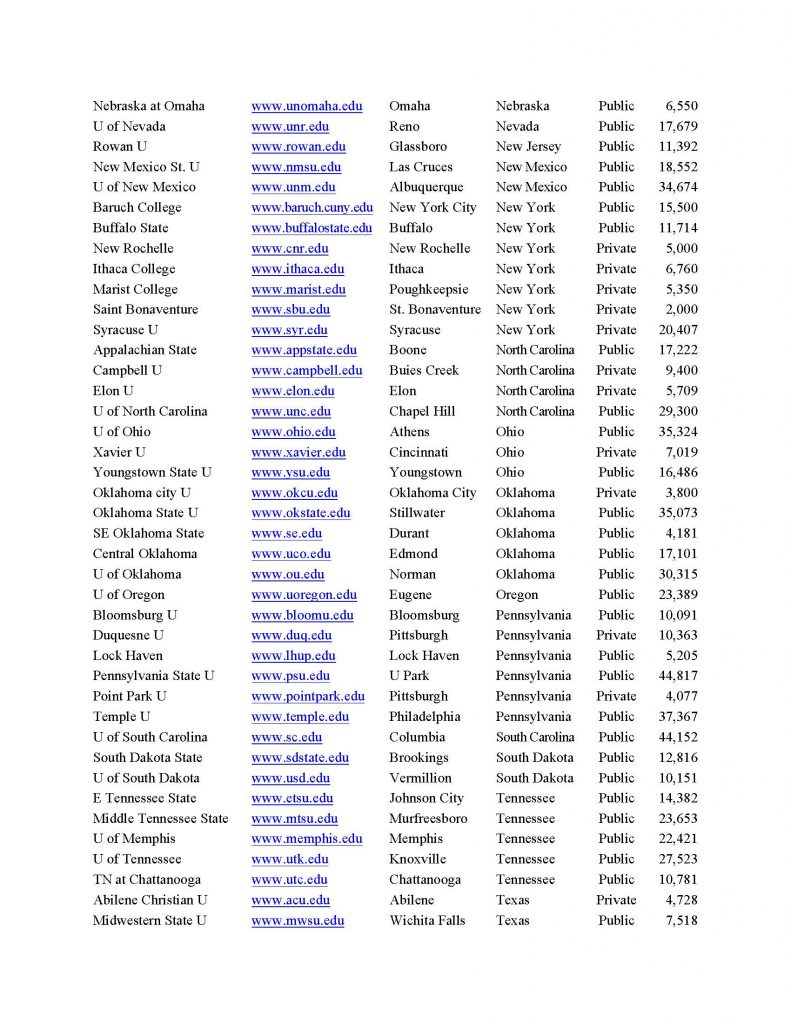

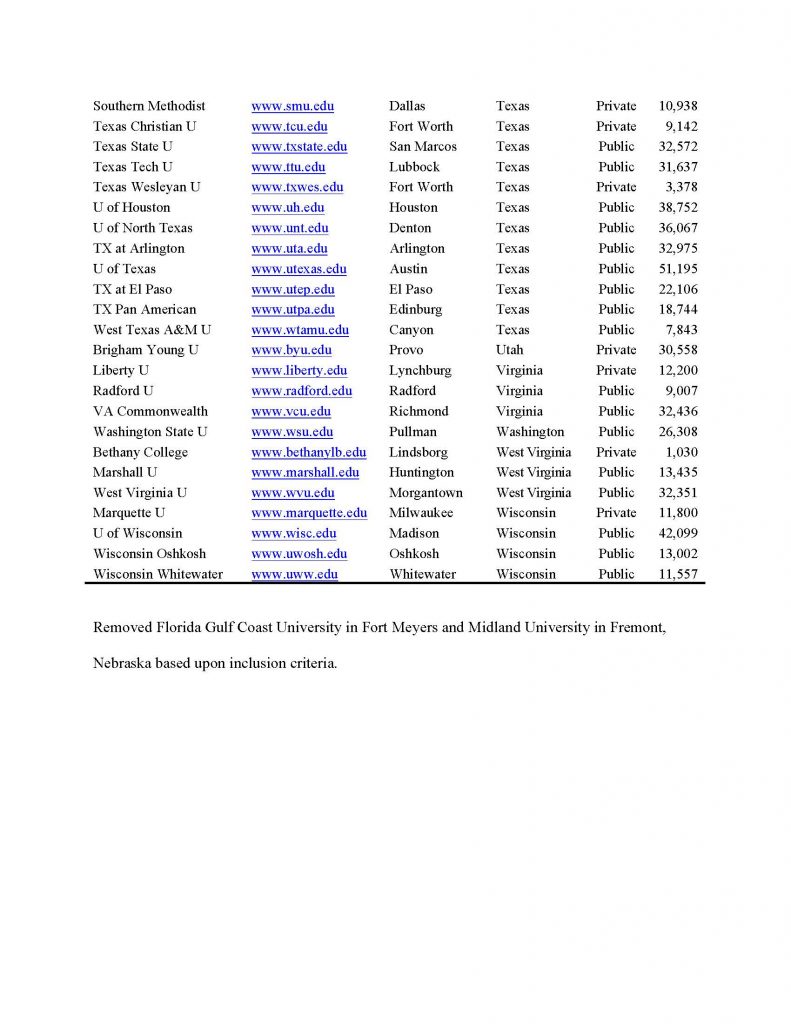

A content analysis was conducted. The unit of analysis was any undergraduate advertising program website. Advertising had to be offered as a major or an emphasis in a related field. Advertising minors were excluded. A list of 145 four-year universities with advertising programs obtained from Ross, Osborne and Richard (2006) was narrowed down to 143, which met the inclusion criteria. For a list of the websites coded, see Appendix A: List of Universities.

Coding Procedure

A codebook and variables were developed based upon an initial screening of the online programs and a review of the literature (e.g., Allen, 1960, 1962; Applegate, 1997, 2007; Duncan et al., 1993; Marquez, 1980; Robbs, 1996; Rose & Robbs, 2001; B. I. Ross et al., 2006; Russell, 1997; Stuhlfaut & Farrell, 2009; Thayer, 1990). Three coders were trained and a pre-test was conducted to measure inter-coder reliability. Each coder worked independently using the same coding instrument applied to a 10% sample (Krippendorff, 1980, 2004). After agreement was reached, each coder analyzed one-third of the sample. Pairwise percentages and Fleiss Kappa were used to calculate agreement for individual variables. Overall, pairwise percentages ranged from 73 to 100%.

Variables

Variables were operationally defined for each specific unit of measurement (Babbie, 1995; Neuendorf, 2002). For tracking purposes, the university name, web address, city and state of the main university campus, institution type (e.g., public, private, other) and total university enrollment were coded. Unless otherwise noted below, variables were coded as one of two categories: “Yes,” from the advertising major or affiliate program website, a link or list of [insert variable here] is available; or “No,” a link or list is not available.

Advertising major. Advertising major is a degree that is awarded by the university in a self-standing and independent program of advertising. The presence of major/degree was identified by the terms “advertising,” “strategic communication” or “integrated communication.” The presences of a non-advertising major was identified by terms such as “journalism,” “communications,” or “mass media.” The categories were “Yes,” advertising is a major; or “No,” advertising is not a major and the name of the degree was recorded. (Pairwise percentage, 73.33%; Fleiss Kappa, .464).

Academic division. The academic division is the college, department or school that directly houses the undergraduate advertising program. For example, if the program is part of Department of Communication in a School of Journalism, the academic division that most directly houses the advertising program is the “Department of Communication.” The name of the academic division was recorded.

Accreditation. Accreditation is the recognition by a national institution of the quality of education or training provided by the academic division. The two major accrediting services that pertain to advertising curriculum are Accrediting Council on Education in Journalism and Mass Communications (ACEJMC) and The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). Categories were “Yes,” the college, department, school or other is accredited by ACEJMC; “Yes” by AACSB; “Yes” by another institution (specify); or “No,” we cannot tell if the college, department, school is accredited (Pairwise percentage, 86.67%; Fleiss Kappa, .722).

Faculty. Faculty is defined as members of the program with a responsibility to teach, excluding staff and graduate instructors. Keywords included “faculty,” “professor,” “instructor,” “lecturer,” “adjunct,” and “chair.” (Pairwise percentage, 100%; Fleiss Kappa, 1).

Advertising faculty. The variable advertising faculty identified if faculty members were labeled or listed according to the program or emphasis: advertising. Keywords identifying faculty as advertising faculty included “advertising,” “strategic communication,” and “integrated communications.” Categories were “Yes,” faculty members are labeled as advertising faculty; or “No,” faculty members are not labeled as advertising (Pairwise percentage, 95.56%; Fleiss Kappa, .956).

Faculty, Ph.D. Faculty, PhD are members of faculty who have earned the highest academic degree. The presence of keywords “Ph.D.,” “Dr.” and “Doctor” were coded as present or not present. The categories were “Yes,” faculty members are labeled as PhD; or “No,” faculty is not labeled as PhD (Pairwise percentage, 82.22%; Fleiss Kappa, .392).

Faculty, professional. Faculty, professional are members of faculty who have worked in advertising or related career fields such as marketing. Categories were “Yes,” faculty members’ titles or biographies list professional experience; or “No,” professional experience is not listed (Pairwise percentage, 82.22%; Fleiss Kappa, .392).

Advertising courses. Advertising courses are advertising specific coursework that are visible and listed within the program’s website by the keywords “advertising,” “strategic,” “integrated,” and “creative.” (Pairwise percentage, 91.11%; Fleiss Kappa, .615).

Required courses. Required courses are those required to fulfill the advertising major or emphasis that are listed within the program’s website by the keywords “required course,” “core course,” “requirement,” etc. (Pairwise percentage, 86.67%; Fleiss Kappa, .177).

Internship program. An internship program is a recognized element of the advertising program and/or academic division that acts as either support services or a requirement. (Pairwise percentage, 85.71%; Fleiss Kappa, .857).

Career placement program. A career placement program includes career services available to advertising students. Career services included job postings, job placement upon graduation, resume building services, and industry connections. (Pairwise percentage, 82.22%; Fleiss Kappa, .63).

Results

The program websites analyzed were for 143 universities in forty U.S. states. The most universities were in Texas (n=14, 9.8%), followed by both Florida (n = 8, 5.6%) and Illinois (n = 8, 5.6%), and finally New York (n = 7, 4.9%). Ninety-seven universities (67.8%) were identified as public universities and forty-six universities (32.2%) were private. Universities ranged in enrollment sizes from 1,030 at Bethany College to 56,337 at Central Florida University.

Online Representation of Undergraduate Advertising Programs

Research question one addressed how undergraduate advertising programs were presented online to potential students. Specifically, we wanted to know if universities listed advertising as a major, what academic divisions advertising programs were listed under, and if advertising programs were identified as accredited. Regarding the variable advertising majors, fifty-three universities (37.1%) identified advertising as a major. The remaining ninety universities (62.9%) did not identify advertising as a major (i.e., advertising was an emphasis, specialization, concentration, etc.). The most common academic division was a department (n=82), followed by a school (n=48), college (n=6), and institute (n=1), or it was non-distinguished (n=6). An example of a non-distinguished division is the advertising major at Xavier University. At Xavier, undergraduates can major in advertising, which is offered in the “College of Arts & Sciences.” Upon entering the webpages for this college, the header becomes “College of Arts & Sciences: Communication Arts.” Therefore, “Communication Arts” was not clearly distinguished as a school, department, etc. within the college.

Academic divisions included the keywords “communication(s)” (n=99), “journalism” (n=54), “advertising” (n=14), “media” (n=9) and “marketing” (n=7).[1] Combinations of keywords included “journalism” and “communication(s)” (n=29), “journalism” and “media” (n=4), “communication(s)” and “marketing” (n=3), “communication(s)” and “media” (n=2), “communication(s)” and “advertising” (n=1), and “advertising” and “marketing” (n=1).

Two types of accreditation were coded: ACEJMC and AACSB. Fifty-one universities (35.7%) indicated the accreditation of their programs. Forty-two universities (29.4%) were accredited by ACEJMC and six universities (4.2%) were accredited by AACSB. Three universities (2.1%) were accredited by other services: Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs and American Communication Association.

Online Presence and Prospective Students

Research question two addressed the online information listed to represent advertising programs and to attract prospective students. Specifically, we asked if faculty members were present and, if so, were they listed by both professional and academic experience; were advertising specific courses listed; were course requirements listed; were internships listed; and were career services listed?

Regarding faculty, the findings show that all but three universities (n = 140, 97.9%) included a list of faculty members. Within the university websites that listed faculty, 120 universities (83.9%) identified faculty by a specialization in advertising. Regarding the identification of faculty members by highest degree earned, 101 universities (70.6%) had visible information of faculty with PhDs on their websites. In terms of faculty with professional experience, ninety-two universities (64.3%) showed professional experience on their websites and/or faculty bios.

Regarding required courses, 122 universities (85.3%) included links or pages of core and/or required courses on their websites. In response to the variable advertising courses, a majority of universities had advertising specific coursework visible and listed within the program’s website (n=118, 82.5%). Analysis found that 128 universities (89.5%) recognized internship programs on their websites and 64 universities (44.8%) included career placement on their websites.

Discussion, Limitations & Future Research

College recruitment models are changing. In today’s digital and competitive marketplace, a thoughtfully developed online presence must be part of a university’s marketing plan. Prospective students use the Internet to collect information about universities they are interested in attending. Similar to evaluations of corporate websites (e.g., Fisher & Arnold, 2002; Qimei, Clifford, & Wells, 2002; Qimei & Wells, 1999), it’s plausible that students evaluate the quality of universities and their programs based on website content. If they are unsatisfied or disappointed by limited information compared to what they expect or to what other universities display, their evaluations and attitudes may be affected. As a result, universities and their respective programs may be losing enrollment to competing programs.

It is important for administrators of these programs to provide information that is easily obtained and understood by prospective students. During search behavior for college selection, according to Chapman’s (1986) college selection theory, a student actively pursues information online. Without a carefully developed online presence, which incorporates relevant information, a prospective student may abandon an institution’s website as well as drop the institution from consideration. The Internet serves as a valuable resource for potential students interested in academic programs. Students are likely to find information on the types of courses they would take, as well as the academic and professional achievements of the faculty who are likely to teach in their desired program. In addition, a comprehensive Internet presence allows students to take a deeper look into their prospective careers through links to internships available, student work and other content. As a result, a potential student using the Internet to learn about programs has the ability to judge the appropriateness of the major based on this additional information. Programs should consider using this additional content to generate excitement and interest in the program, and move beyond the simple “online catalog” framework that is so often used by programs. It is also a way for programs to highlight their competitive strengths and showcase student work to a broader audience.

While we do not recommend standardizing something as creative as a website, we do, however, based upon college selection theory, recommend that advertising programs consider what information is provided. For example, in 2005, advertising faculty had an average 12 years of professional experience (Ross & Richards, 2008). However, according to our findings, 64.3% of program websites listed professional experience on faculty pages. In addition, 82.5% of program websites listed advertising courses and 85.3% listed required courses. While the percentages appear high, 15 to 20% of program websites did not list required courses or advertising courses in general, which seems counter-productive to the information search process during college selection.

Based on our findings, we make three recommendations. First, advertising programs should be clearly labeled and defined. Through the years, advertising programs have been called majors, specializations, concentrations, etc. (Ross, 1965). Any non-major classifications, including the 90 programs analyzed as “specializations” or “concentrations,” may be confusing to potential students on just what degree they will end up with if they study advertising. So, for example, if advertising is a “specialization,” define what that means for the student and list requirements so that prospective students can evaluate the program’s offerings. Second, prominently display faculty members as well as their academic and professional achievements. Advertising faculty with both scholarly competence and industry experience impacts the undergraduate program and the students’ learning outcomes (Banning & Schweitzer, 2007). And third, prominently display prospective advertising careers as depicted through internship opportunities and career services. Internships are an important part of the educational process, providing the experience students need to succeed (Banning & Schweitzer, 2007; Gifford & Maggard, 1975). Participating in internships not only gives students hands-on experience making them more marketable, but it also provides a trial run in their prospective career.

It is important to address what was not analyzed in the current study. We did not analyze the advertising program itself. The current content analysis examined the online representations of advertising programs. Therefore, it is not assumed or implied that an aspect of the program missing online is missing from the program altogether. In addition, what are not reflected in our results are the elements of layout, design, SEO and the usability of university websites. Due to confusing webpage layouts during a preliminary review of websites, certain variables such as elements of usability were not included in this study. For this reason, however, the elements of design and navigation are worth mentioning. Programs should be aware of possible navigational challenges that may impede the ability of a prospective student to fully understand the academic program offered. Once a student has decided to research a university online, the navigational challenges that we experienced will likely frustrate him/her as much as it did us. This frustration also highlights a potential opportunity for research and practice. Future research could examine the design, layout, navigation and search terms (for SEO) of program websites and offer recommendations for a website that is not only comprehensive, but also clearly identifiable, user-friendly and search engine optimized. Universities have an opportunity to refine content presented online, which not only informs prospective students about the program, but also represents the image and values of the university. While this study does not propose recommendations for design and optimization, the findings present the first analysis of advertising program online content, which lays a foundation for future research and recommendations.

References

Allen, C. L. (1960). Survey of advertising courses and census of advertising teachers. Paper presented at the American Academy of Advertising, Stillwater, OK.

Allen, C. L. (1962). Advertising majors in American colleges and universities 1962. Paper presented at the American Academy of Advertising, Stillwater, OK.

Anctil, E. (2008). Marketing and Advertising Education. ASHE Higher Education Report, 34(2), 19-30.

Anderson, C. E., & Reid, J. S. (1999). Are Higher Education Institutions Providing Collegebound high school students with what they want on the web? A study of information needs and perceptions about university and college web pages. Paper presented at the Symposium for the Marketing of Higher Education.

Applegate, E. (1997). Advertising. In W. G. Christ (Ed.), Media Education Assessment Handbook (pp. 319-339). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Applegate, E. (2007). The Historical Development of the Advertising Curriculum. Journal of Advertising Education, 11(2), 5-9.

Banning, S. A., & Schweitzer, J. C. (2007). What advertising educators think about advertising education. Journal of Advertising Education, 11(2), 10-20.

Barnes, B. E., & Lloyd, C. V. (2000). Advertising curriculum review: case studies of two alternate approaches. Journal of Advertising Education, 4(1), 39-47.

Becker, L. (1990). Finding work was more difficult for graduates in 1990. Journalism Educator, 47(2), 65-73.

Blakeman, R., & Haley, E. (2005). Tales of portfolio schools and universities: working creatives’ views on preparing students for entry-level jobs as advertising creatives. Journal of Advertising Education, 9(2), 5-13.

Blanchard, R. O., & Christ, W. G. (1993). Media Education and Liberal Arts: A Blueprint for the New Professionalism Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associated.

Bok, D. (2003). Universities in the marketplace: The commercialization of higher education. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Chapman, R. G. (1986). Toward a theory of college selection: A model of college search and choice behavior. Advances in Consumer Research, 13, 246-250.

Christiansen, D. L., Davidson, C. J., Roper, C. D., Sprinkles, M. C., & Thomas, J. C. (2003). Getting Personal with Today’s Prospective Students: Use of the Web in the College Selection Process. College & University, 79(1), 9-14.

Clayton, M. (2003). Speed-selecting a college. http://www.csmonitor.com/2003/1007/p13s02-lehl.html

Duncan, T. R., Caywood, C. L., & Newsom, D. (1993). Preparing Advertising and Public Relations Students for the Communications Industry in the 21st Century: A Report of the Task Force on Integrated Communications.

Gifford, J. B., & Maggard, J. P. (1975). Top agency executives’ attitudes toward academic preparation for careers in the advertising profession in 1975. Journal of Advertising, 4, 9-14.

Hartman, K. E. (1997). College Selection and the Internet: Advice for Schools, A Wakeup Call for Colleges. Journal of College Admissions, 154, 22-31.

Hossler, D., & Gallagher, K. S. (1987). Studying student college choice: A three-phase model and the implications for policymakers. College and University, 62(3), 207-221.

Kotler, P. (1976). Applying market theory to college admissions. Paper presented at the Colloquium on college admissions: A role for marketing in college admissions, New York: College Entrance Examination Board.

Kotler, P., & Fox, K. F. (1995). Strategic marketing for educational institutions. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Kotler, P., & Kotler, M. (2013). Market your way to growth: 8 ways to win. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Lee, T.-T., & Ryan, W. E. (2005). Advertising creative practitioners on the value of advertising education: an overview. Journal of Advertising Education, 9(2), 14-21.

Lovelock, C. (2001). Services marketing: People, technology, strategy. London: Prentice Hall.

Lowry, D. T., & Xie, L. T. (2008). Employers’ perspectives on skills needed for entry-level advertising and marketing jobs: a new computerized approach. Journal of Advertising Education, 12(2), 17-24.

Maringe, F. (2006). University and course choice: Implications for positioning, recruitment and marketing. International Journal of Educational Management, 20(6), 466-479.

Marquez, F. T. (1980). Agency presidents rank ad courses, job opportunities. Journalism Educator, 35(2), 46-47.

Plank, S. B., & Jordan, W. J. (2001). Effects of information, guidance, and actions on postsecondary destinations: A study of talent loss. American Educational Research Journal, 38(4), 947-979.

Robbs, B. (1996). The Advertising Curriculum and the Needs of Creative Students. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 50(4), 25-34.

Rose, P., & Robbs, B. (2001). Multicultural Issues in the Advertising Curriculum. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 55(4), 30-38.

Ross, B. I. (1965). Advertising education: Programs in four-year American colleges and universities. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech Press.

Ross, B. I., Osborne, A. C., & Richards, J. I. (2006). Advertising education: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Lubbock, TX: Advertising Education Publications.

Ross, B. I., & Richards, J. I. (2008). A Century of Advertising Education: American Academy of Advertising.

Russell, J. T. (1997). Advertising education: Where are we, where are we going. Journal of Advertising, 6(1), 50-51.

Spiller, L. D., Marold, D. W., Markovitz, H., & Sandler, D. (2011). 50 ways to enhance student career success in and out of advertising and marketing classrooms. Journal of Advertising Education, 15(1), 65-72.

Stuhlfaut, M. W., & Farrell, M. (2009). Pedagogic Cacophony: The Teaching of Ethical, Legal, and Societal Issues in Advertising Education. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 64(2), 173-190.

Thayer, F. (1990). PACE model gives advertising campaign-centered curriculum. Educator, 45(1), 78-81.

Appendix A

Acknowledgements

This academic article was accepted for publication in the International HETL Review (IHR) after a double-blind peer review involving several independent members of the IHR Board of Reviewers and several revision cycles. Accepting editor: Dr Charlynn Miller.

Suggested citation:

Schauster, E., Lee, J., Ferrucci, P., Kim, S., & Sheehan, K. (2016). Get with the Ad program: Website content analysis. International HETL Review, Volume 6, Article 5, https://www.hetl.org/get-with-the-ad-program-website-content-analysis/

Copyright [2016] Erin E. Schauster, Joonghwa Lee, Patrick Ferrucci, Seoyeon Kim, Kim Sheehan

The authors assert their right to be named as the sole authors of this article and to be granted copyright privileges related to the article without infringing on any third party’s rights including copyright. The authors assign to HETL Portal and to educational non-profit institutions a non-exclusive licence to use this article for personal use and in courses of instruction provided that the article is used in full and this copyright statement is reproduced. The authors also grant a non-exclusive licence to HETL Portal to publish this article in full on the World Wide Web (prime sites and mirrors) and in electronic and/or printed form within the HETL Review. Any other usage is prohibited without the express permission of the authors.

Disclaimer

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author, and as such do not necessarily represent the position(s) of other professionals or any institution. By publishing this article, the authors affirm that any original research involving human participants conducted by the authors and described in the article was carried out in accordance with all relevant and appropriate ethical guidelines, policies and regulations concerning human research subjects and that where applicable a formal ethical approval was obtained.

[1] Division titles had multiple keywords, therefore the totals exceed 143.